READING LIST

A Fictional Life Raft for

Surviving Whatever Comes Next

Katie Goh

Issue 4, October/November 2021

I have been alive on this planet for nearly three decades and the world has already ended. In fact, it’s ended hundreds of times. And it’s begun again. Again, and again, and again.

Hollywood movies may have turned the apocalypse into a singular Event — a spectacular, one-off cataclysm that has a B.A. (Before Apocalypse) and an A.A (After Apocalypse) — but anyone alive right now can testify that it feels like the world has been ending a little bit more every day. For many Anglo-American, middle-class liberals, it felt like the political apocalypse took place in 2016, following the Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s inauguration. But surely western politics ended when George W. Bush declared an invasion after 9/11, or after the Berlin Wall fell, or after Ronald Regan’s election, or after Adolf Hitler took power in 1934? And what about personal apocalypses?: Every day, someone is going through their own end-of-the-world scenario, whether that’s a loved one dying, or a painful break-up, or being made redundant. COVID-19, a global pandemic that ground the world to a halt, was a life-changing disaster, but was it The Apocalypse? If you’re reading this now, I think it’s safe to say the world didn’t end in 2020.

“The heavenly scene: a throne room where

God sits surrounded by 144,000 elders,

seven flaming torches, and four minotaur-

like creatures with six wings and the

heads of a lion, ox, human, and eagle,

respectively.”

No idea what Revelation actually says?

Let Emily Manthei help: “Apocalypse, Now?“

The apocalypse in our collective cultural imagination is a cycle of regeneration: a disaster followed by a redemption. This has been cemented in western culture since the biblical book of Revelation, arguably the most influential fictional end-of-the-world scenario ever dreamt up. In Revelation the world is stripped down to its studs and remade entirely anew, a vision of hope in a politically, environmentally and socially turbulent time — Revelation was written just decades after Jesus’ death and Mount Vesuvius’ eruption. Skip forward centuries and Revelation’s narrative arc still looms over how we imagine the end of the world: it’s there in our superhero movies and in our environmental disaster stories and in our modern-day technological anxieties.

Apocalypse stories remain popular because they have neat beginnings, middles and endings. These books, movies, television shows and games depict the end of the world as a singular apocalypse à la the Book of Revelation. They offer structure, narrative and arc at a time when the world feels like it’s in a sprawling, unwieldy freefall, whether that’s due to the climate crisis, a pandemic, or dangerous politics. Disaster fiction makes unbearable prospects bearable, even enjoyable. It turns them into art, into something that can be held at arm’s length, imagined and interpreted at a safe distance. Our very real catastrophes become manageable as metaphors.

They can also strike us anew as fiction. While capitalism’s inhumanity is normalized as a foregone conclusion to being a member of society, a television show like Squid Game can present cruel economic structures in a new light through genre tropes and metaphoric allegory. (After all, isn’t it easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism?)

Let Pipe Wrench throw you a life raft.

The Greek roots of the word “apocalypse” mean to uncover or reveal. What does our fascination with fictional disasters reveal about us? That we want stories that show us where we are going — stories that imagine the future we are already on the road to, whether that’s a dystopia, a utopia, or something in between the two. Or perhaps we fantasize about future apocalypses in our art and imaginations because we need to know that this, surely, isn’t the worst it can get.

We are living in apocalyptic times. This is not a new phenomenon (has there ever been a point in human history not plagued by catastrophe?) but that fact doesn’t make being alive right now feel any easier. I spent most of 2021 reading and watching apocalyptic stories while writing my own book about popular disaster fiction. Immersed in the end of the world, I discovered that apocalyptic desire — that craving to end the world and start again, that little voice in your head that tells you it’s easier to throw in the towel, to give up, to say fuck it, let the sea levels rise and the sky fill with toxic fumes — is essential for our collective survival. Apocalypse stories speak more to our current moment than they do to some far-flung future; the Book of Revelation, after all, is a political and allegorical text that tells us more about what it was like to be alive during its author’s lifetime than what it will be like to be alive during some impending cosmic battle.

As we continue to try and survive in a world that feels like it is continually ending, perhaps apocalypse fiction can offer us a life raft — not to escape from our real disasters but to reveal them, and to equip us with the tools we need to face them head on.

“Then her own mother’s voice, Reba

nearly laughing into the night: ‘Keepon fussin’ momma. You just keep on.'”

Not ready for a book? Try some short

stories: “Thy Father and Thy Mother,” Taylor Byas.

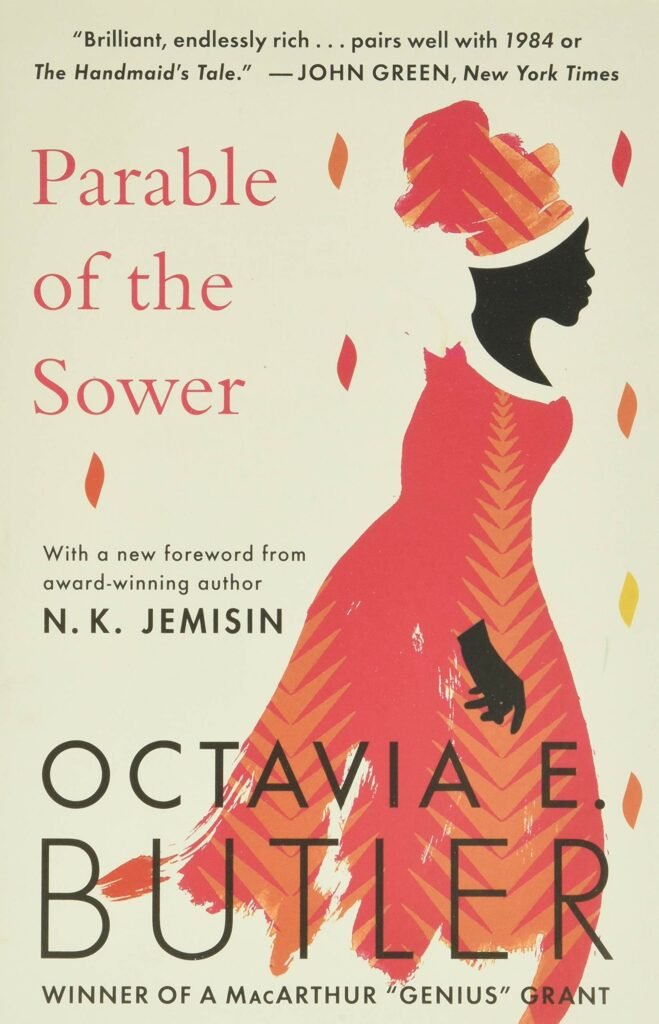

Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler

Decades before “Make America Great Again” made its way onto red caps, Butler wrote the phrase in her dystopian novel. Parable of the Sower’s world is grimly prescient, but offers optimism in its central character, Lauren, a young, Black woman who must lead a band of survivors to safety.

Kajillionaire, directed by Miranda July

Maybe not an obvious apocalyptic tale, but July’s film is a wonderful example of how a literal and metaphorical disaster (in this film, an earthquake) can change the course of a person’s life.

The Disconnect: A Personal Journey Through the Internet, Roisin Kiberd

This book of funny, nihilistic, intelligent essays takes on the apocalypse in technology, from dating apps to Silicon Valley.

“The tracks in Songs in the Key of Doom

connect the apocalyptic outlook of our

times to the controversial texts and

interpretations of the Book of Revelation

— but with a groove.”

Cut an end-times rug with Brandon

Ousley’s playlist: “Songs in the Key of Doom.”

Punisher, Phoebe Bridgers

Music is rarely labelled “apocalyptic,” but Bridgers’ album captures the end of the world as lived through by the millennial generation: numb, mundane, paralyzing.

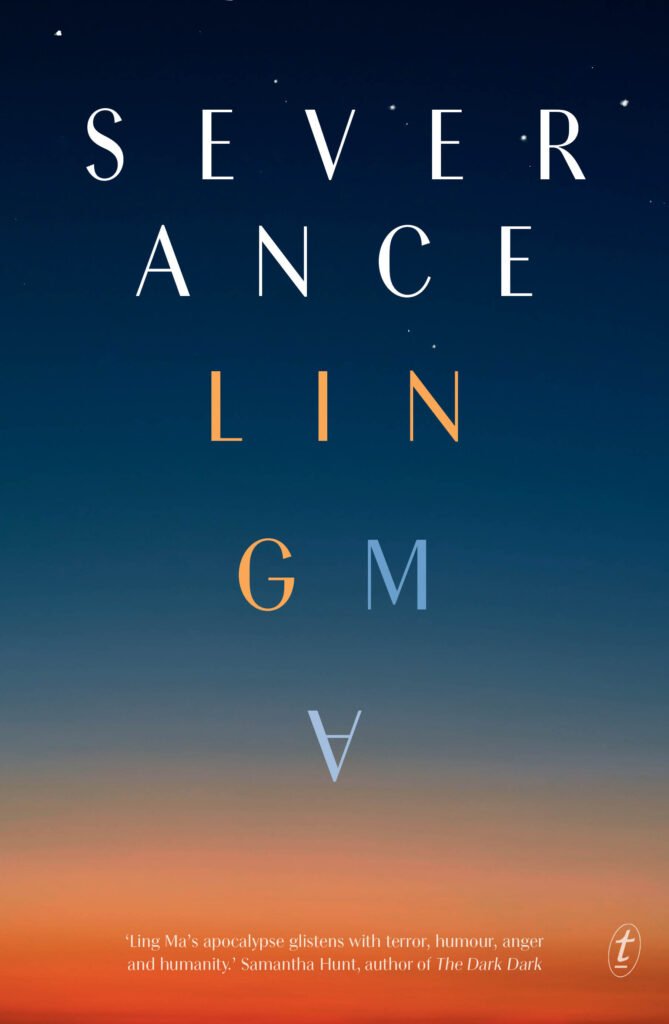

Severance, Ling Ma

Ling Ma’s 2018 pandemic novel got a second wave of attention in March 2020 for featuring a virus similar to COVID-19, but the real parallel between Ma’s fictional apocalypse and our own is the relentless, brutal grip capitalism has on our imagination.

“Story of Your Life,” Ted Chiang

Ted Chiang’s short story was adapted into the feature film Arrival; it follows a linguistics professor who must learn to communicate with aliens that have recently arrived on Earth. Determinism and fate are the story’s main themes as its protagonist weighs up whether to embrace her destiny.

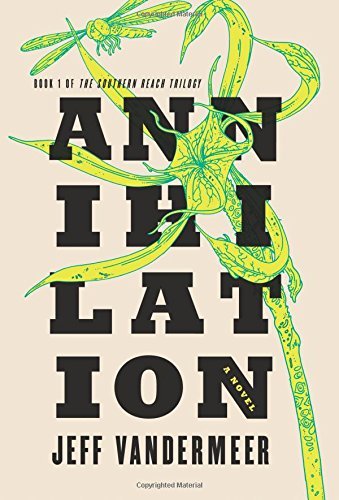

Annihilation, Jeff VanderMeer

The first novel in Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy is about a hostile, sprawling environment called Area X, which was inspired by real life oil spills. Annihilation captures just how weird the climate crisis is, as well as the paralysis caused by climate grief.

Katie Goh is a freelance writer, critic and editor based in Edinburgh. Her new book, The End: Surviving the World Through Imagined Disaster, is available now.

Next

Surviving catastrophe requires dealing with life as it comes, which is at odds with the priorities of so many faith leaders — and not just Christians:

“Closer to My Religion,” by Anmol Irfan.

Previously

Three brief glimpses at three possible futures:

“The End, The End, The End,” by speculative fiction writer Kel Coleman.

Or browse the rest of the issue.