This story is adapted from chapter one of Acquired Tastes: Stories about the Origins of Modern Food from the MIT Press “Food, Health, and the Environment” series.

On May 11, 1880, Walter Crow was shot in the back as he ran through a wheat field. Two tendrils of smoke wafting from a stand of oak and sycamore behind him gave away the location of his killer. Minutes prior, Crow had murdered four others in fifteen seconds with a brutally efficient double-barreled shotgun.

Earlier that day, farmers from around the countryside had gathered to hear Judge David Terry, who was scheduled to speak on the tangled mass of land and water rights that had piled up in California over the previous twenty years. As the farmers picnicked, United States Marshal Alonzo Poole prepared for his day’s task, a land grab: serving eviction notices to farmers along a patch of land called Mussel Slough to make way for a railroad. As an armed group coalesced around Poole, rumors of the evictions washed over the farmers. They grabbed their own guns and rode off.

The two armed groups met by Henry Brewer’s farmstead. The marshal dismounted and stood; heated words were exchanged. Suddenly, two men — farmer James Harris and pro-railroad Mills Hartt — opened fire on each other. Harris’ bullet hit Hartt in the groin. Seeing his friend Hartt fall, Walter Crow raised his shotgun. A noted marksman, Crow hit Harris in the chest, killing him instantly, before turning and opening on Iver Knutson, dropping him as well. Next, he swiveled and unloaded on farmer Daniel Kelly “so that the charge entered [his] side and practically blew it off,” then jumped off his wagon and ran towards Archibald McGregor, who was using the marshal’s horse as a shield. Crow wheeled around the horse and shot McGregor twice in the chest. Farmer John Henderson had managed to jump off his horse and aim at Crow; they rushed each other and exchanged four shots, and Henderson was dead. Crow then ran towards the maturing wheat, crawling to remain hidden as two unknown settlers pursued. As Crow neared his house and what he thought was safety, he stood and broke into a sprint. Two shots rang out and Crow fell.

Back then, it was the anti-rail settlers

“Bypassed,” Lisa Lee Herrick

versus the U.S. government at Mussel Slough,

near Hanford. It was a flash- point of

violence united by mutual hatred of the

“Indians,” and the forceful seizure of

fertile indigenous lands. Today, their

descendants raise political billboards

railing against the crumbling of American

traditions along the highways, urging

voters to build walls keeping out foreign

invaders and the same brown hands laboring

in the fields and orchards from dawn to

dusk. Hands like mine.

So, same difference.

Every man who fired a shot that day — except Crow’s anonymous killers — lay either dead or seriously wounded. (Harris died of his injuries four days later.) The initial volley of gunfire had lasted less than twenty seconds. Neither Wild Bill Hickok, Wyatt Earp, nor Billy the Kid ever killed as many people in a single incident as Walter Crow.

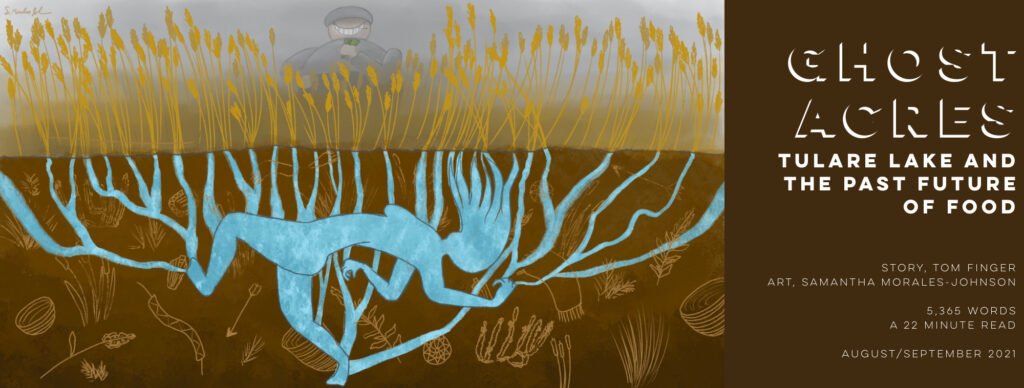

Today the field where Crow died lies in modern-day Hanford, California, about 35 miles south of Fresno in California’s Central Valley. Among the ghosts of Crow, Hartt, and Harris, you’ll find another, much larger one: shrouded by fields of soybeans, alfalfa, and corn, Tulare Lake lies hidden. What was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River is now rows of grain crops and vegetables. These crops feed millions of people across the world on the stored wealth of an ecosystem cultivated over generations by the Yokuts people.

The shootout was no simple competition between farm and railroad. It was, rather, a culminating flash of violence as settlers wrested land from indigenous peoples and plugged it into the global food economy — less an “Old West” story than one about the origins of our food systems.

Each jar of peaches or glass of milk produced on Tulare bottomland owes a portion of its nutrients to the land and water management of the ancestors of those who live and work almost within sight of the dried lake, and its existence to layers of violence.

The Mussel Slough Tragedy drenched the dry, maturing wheat fields with blood, but violence was already endemic to the land. During the second half of the nineteenth century, an abundant landscape of tule marshes and oak stands that fed Yokuts peoples transformed into a giant wheat field feeding industrialization in England. This involved human violence as well as ecological collapse, creating a landscape that historian Kenneth Pomeranz refers to evocatively as ghost acres: acres of land outside the U.K. hijacked to produce resources to fuel industrialization and population growth within the U.K. Ghost acres are in a state of suspended animation — complex seasonal networks of food production homogenized into uniform suppliers of western capitalism.

Alang is a hazardous modern-day

“The Ghost Acres of Gujarat,” Ayushi Dhawan

ghost acre: land that takes the

toxic waste countries don’t want

to burden their own populations with.

Modern food is not just the products on the shelves, but the acres and people transformed so we can consume those products. The nineteenth century laid the groundwork for those new places and Tulare Lake, a ghostly landscape, is an example of the violence written into them. Its history can help us wrestle with the full brunt of food choices, and how the health of bodies is entwined with our current food system, its past — and its future. Each jar of peaches or glass of milk produced on Tulare bottomland owes a portion of its nutrients to the land and water management of the ancestors of those who live and work almost within sight of the dried lake, and its existence to layers of violence. Understanding those histories can help guide the ecological and human reanimation of ghost acres.

Let me take you now to Ciau, a village just north of Tulare Lake, in 1840. The now-disappeared Nutunutu band of the Yokuts people migrated around their central village, making use of the valley’s rich ecological diversity and seasonal patterns of productivity to forge a healthy and resilient diet. Nearby, a seasonal channel later called Mussel Slough moved water back and forth between the Kings River and Tulare Lake. Here, Yokuts women migrated to find food according to the pulses of seasons.

Priceless knowledge about where food

“This Is the Old Way That’s Also the New Way,”

and medicines grow and what their uses

are were passed down generation after

generation. We taught one another about

migration patterns, cycles, seasons,

and the movement of the stars.

Ruth Hopkins

The women of Ciau understood this was a place of dramatic variation in water and temperature. Prior to the late nineteenth century, the San Joaquin Valley surrounding Tulare Lake was a patchwork of niches, running the ecological gamut from alkaline desert to lush riparian forest. The western portions of the Tulare Basin lay in the rain shadow of coastal mountain ranges and were the most arid regions of the valley. Moving further east, alkaline flats gave way to short grasslands. These grasslands in turn transitioned to salt marshes that thrived along the lake’s wavering shoreline. Tall grasslands predominated as the land rose from lake to foothills covered in oak parkland. Tendrils of sycamore forest clung to waterways that cut towards the lake.

You’ve been reading Pipe Wrench.

It’s magazine that’s also a conversation: one longform feature surrounded by a constellation of interpretations, asides, and digressions.

We love excellent storytelling, fair pay, and the 1985 song “Take On Me.”

Learn about what we’re making and how we’re making it.

Tulare Lake itself filled entirely from snowmelt in the Sierra Nevada Mountains each spring, and would shrink considerably in the hot, dry summer months. Dimensions changed dramatically from season to season, and year to year; the lake measured only forty feet deep at its deepest location, and in many places it was shallow enough for someone to wade out a mile and still only be up to their shoulders. In wetter years, Tulare could cover as many as 1,800 square miles. Early surveys record the area around the lake as “overflow and swamp,” and early White settlers recorded extremely wet years in 1852, 1858, 1860, and 1868. Despite this, the lake almost dried completely in 1854. One local newspaper reported in 1890 that the lake had spread out a full fifteen miles during the spring season at a rate of about a mile and a half a week. Another early settler remembered “the shore lines of Tulare lake changed and shifted a great deal. If a strong wind came from the north, as it often did, the water would move several miles south, and would move again when the wind changed. Then when the water level in the lake changed the shore line shifted a long distance.” This hydraulic metabolism created a rich diversity of ecological niches surrounding the lake, including Mussel Slough and nearby Ciau.

The environments of the Tulare region produced what ecologists call the portfolio effect: no matter what the season or weather conditions, some resource was experiencing peak productivity. The area must have been beautiful, and certainly was bountiful. One White settler recalled wistfully, “I have always remembered that place as one of the most ideal I have ever seen. The tall green grass, the cool clear water, and the trees with their fresh leaves made as pretty a sport as one could wish… for my own part, I have never seen anything equal to the virgin San Joaquin Valley before there was a plow or a fence in it.”

I look back on my childhood with fond

“This Is the Old Way That’s Also the New Way,”

memories of working the soil in my

mother’s garden; picking Native fruits,

berries, prairie turnips, wild onions,

and medicines in the wild; hunting and

fishing with my father; and then skinning,

butchering, drying, canning, pickling,

and freezing what we’d collected. Our

pantry was always full, and we gladly

shared our bounty with friends,

neighbors, and relatives.

Ruth Hopkins

Before the latter nineteenth century, we know the inhabitants of Ciau rarely — if ever — went hungry. As one early settler history of Tulare County recounts, “Acorns, of course, were the staple, but it is a mistake to suppose that the Indians’ diet lacked variety. In addition to game of all kinds and fish, there were various kinds of seeds, nuts, berries, roots, and young shoots of the tule and clover.” There were once actually mussels in Mussel Slough, which the Nutunutu collected and boiled in fine-woven baskets filled with hot stones.

As temperatures cooled in the fall, Yokuts women left Ciau for their seasonal camp in the oak-studded foothills some 40 miles to the east. Here, acorns dropped from oaks fertilized by fires delicately managed by the village’s men a few months prior. Women would collect piles of acorns at the creek side and break them down into a rough flour using a mortar and pestle fashioned from a tree trunk and large branch before pounding the flour into a cake and letting dry on a rock.

Prescribed by my doctor, the diet

“Wung Whikyung Na’way,” Kayla Begay

looks to me like a map of Indigenous

North America, with foods like sa’liwh

(fresh leafy greens) and ło:q’ (salmon).

What I am hearing: my body is on fire

like the land without big runs of ło:q’

and the plant foods my people stood in

relationship with since time immemorial.

With abundant food, there was little open conflict between the Tachi, Nutunutu, and many other Yokuts bands migrating around their central place. Then came consecutive blows to the Nutunutu and larger Yokuts communities in the first half of the nineteenth century. First was the expansion of the Spanish mission chain up the Pacific Coast. Because Ciau sat well inland, the major impact from the missions was with the introduction of grazing animals, whose ranging contributed to the collapse of native grasses and reintroduction of foreign species. As Spanish and Mexican cattle herds fanned out across the valley, native plants died and the Nutunutu saw some strands of their dietary network collapse. Throughout the early nineteenth century, they, like many other Yokuts bands, made up for the loss of native species by adopting the horse to ride, raid, and eat.

Even as they made these adaptations, other forces conspired. In the early 1830s, malaria swept in, carried by traders for the Hudson Bay Company. Finally, in the 1840s came the cataclysm of gold mining and Anglo settlement. The next half century would see the remaking of this place as a depot for global trade, a place where violence shook food systems that had before been marked by self-reliant sustenance.

As the Nutunutu found their dietary network stressed, halfway across the world so too did the poor workers of Manchester, England, suffer. The two communities were eventually linked by the flow of wheat grown on stolen Nutunutu land in California and shipped overseas to feed the industrial English workers with cheap bread. Manchester qualified as a village at the beginning of the 1700s and was only given representation in Parliament in 1832. But as the Nutunutu reeled from disease, it became a fast-growing city of shanties, warehouses and manufactories. The centrifugal forces of land dispossession and food commercialization forced people to migrate from farm to cities. Manchester was a city of hungry refugees.

London and Manchester teemed with

“It Was That Or Starve,” Laurie Penny

destitute, desperate people for whom

Victorian morals were just another

luxury designed to separate rich and

poor: what good was a priest or a

policeman telling you not to steal,

swindle, or fuck for money if it was

that or starve? So much of the political

and economic thinking that is still

considered foundational is a reaction

to these man-made contradictions.

Across England in the nineteenth century, many working-class women felt the daily brunt of these systemic changes to their food economy. Subsistence landscapes transformed into commercial farms. Growers became eaters. The life of an English rural family prior to being kicked off their land would have been seasonal in nature, not terribly unlike that of the Nutunutu. Families would have lived in the same houses year-round, their lives dictated by fallow-rotation farming. They fished in local creeks and used forests, fens, and unplowed fields as sources of game, herbs, and root vegetables. But accelerating enclosure consolidated land rights in the hands of a country gentry, and portions of the English rural foodway began to crumple. Long rows of turnips, barley, and oats turned into geometric wheat fields. Forests were felled and plowed into fields. Experts drained fens, devised new labor-saving machines, and innovated fallow patterns designed to feed cities bulging with the very people who had once worked the land.

Just like the Nutunutu, unsettled English people in the nineteenth century moved around a central place. Crucially, though, this was a migration borne of desperation, not seasonal forage. Most would come to work in burgeoning towns like Leeds, Birmingham, and Manchester, but hunger and housing prices kept them ever on the move. These industrial settlements were places of work opportunity but little dietary resiliency, as people worked all day in foodless environments; there was little room for gardens in tightly-packed neighborhoods. Women often bore the brunt of these problems: not only would they shoulder the stress of obtaining and cooking enough food for their families (and anyone else who might be living in their crowded quarters) while also often supplementing the family’s income through wage work, they were often expected to be the first to forgo food in times of shortage, leaving sufficient food for the male “breadwinner” and the children, supplementing their diets with energy-packed, nutrient-deficient sips of tea and bites of candy. Women’s mental and physical health suffered.

The theorists and practitioners of

“To Subsist,” Sherene Seikaly

development and modernization have

waged war on subsistence for nearly

a century. They preached: It is

primitive, irrational, wretched,

impoverished, and premodern to

subsist. They preached: Our history

and our present are inevitable,

linear, progressive. They preached:

There is no alternative.

This situation reached a crisis point in the 1840s. For so many English working-class women in the nineteenth century, universal suffrage and politics in general were “knife and fork” questions about eroding the power of the landowning class who, through enclosure, had simultaneously cast people from traditional lands and made them dependent on the whims of the market. Merchants and laborers in newly industrial cities rose to the cry of suffrage and cheap bread. Atmospheric conditions over the North Atlantic pumped a depressing slate of cool, wet weather over northern Europe. Crops failed. Women and their families went hungry everywhere in the British Isles and northern Europe. While the “hungry forties” are most well-known from the Irish Potato Famine, the poor all over Europe found their dietary stress dip into outright starvation. And so, England — and the poor of Manchester — cast a hungry eye out across the world.

At the same time, Yokuts women noticed strangers in their oak stands. American settlers in the 1840s and 1850s preferred to settle in the oak-blanketed foothills of the eastern slopes of the Tulare region not because of the acorns they contained, but as refuge from the floods and seasonal swampland that characterized much of the valley’s bottom. Here, settlers began planting wheat and alfalfa, girdling or cutting down so many of the acorn trees those of Ciau had worked so hard to keep. Much of this crop went to feed magnate Henry Miller’s vast cattle empire, sprawling as it was across the central portions of the valley. These crops were consumed by both cattle workers and their charges which, slaughtered and butchered, fed hungry miners toiling on busted claims high in the mountains.

Later arrivals moved into the marshlands below. Businessmen lurked for profit and new passions inflamed old land disputes. Failed miners and desperate emigrants rushed to the Tulare region to make quick cash from cheap Native land, often just given away by the new state government. What couldn’t be taken legally was taken by force.

You divide what’s left of us

“This Poem Is Taking Place on Stolen Land,”

onto shrinking soil / and pluck

acorns and yucca blossoms from

our fists. / We are sun-dried

gills, rising and falling.

Emily Clarke

In a story of violent place-making that repeated itself thousands of times across the globe in the nineteenth century, newly arrived White farmers in the Tulare region went to war with the remnants of Ciau and other Yokuts communities in 1856. Farmers formed a militia after drumming up an excuse, intent on asserting their settler campaign. The few remaining Yokuts living in remnant villages scattered throughout the Tulare region rightly saw that the settlers’ preparations would lead to a punitive expedition. They headed into the foothills for protection. Ciau emptied, never to be filled again.

Just days ago, the fire crept up

“Wung Whikyung Na’way,” Kayla Begay

its side in the steep river canyon

and into Hupa speaking territory.

Evacuations of the town of Burnt

Ranch, named in English for a

village burned out by miners in

Gold Rush times, happened yesterday.

The militia group chased the refugee community to the foothills and sought to dislodge them. Their first attack was unsuccessful, but aid from a federal cavalry unit stationed just south of the valley ultimately helped them overwhelm the Yokuts, sending survivors scattering into the mountains. For weeks after, the militia and federal cavalry rode across the countryside, alternatively killing or gathering any Native person they found and incarcerating the survivors at the Kings River Indian Reservation just south of Fresno. And so, through the cumulative force of disease, environmental change, and state violence, the landscape of Tulare became unmoored in the global economy, its people killed or captured.

Into this scene stepped Isaac Friedlander, a six-foot-seven, three-hundred-pound German immigrant whose shadow would loom large over the Tulare Valley for the next twenty years. Friedlander was at first as unmoored as the Tulare landscape he would come to own. After a series of failed business ventures on the East Coast, he came to California in 1849 hoping to strike it rich. He failed some more, and tumbled back to San Francisco in 1852 to reevaluate his business prospects. He read reports streaming back from the interior of “wars” that were clearing the Yokuts, Wappos, Miwoks, and Patwins from their lands. He also happened to meet two very important businessmen, banker William Ralston and land lawyer William Chapman.

Never miss an issue.

We’ll send you a newsletter.

Together, Ralston, Chapman, and Friedlander hatched one of the most crooked land schemes in American history, sowing the seeds of Tulare Lake’s demise by connecting it to Manchester. No longer would the food ecology of Tulare be controlled by temperature and moisture, but by account balances and inter-firm competition.

Ralston bankrolled the operation with gold-backed securities from his Bank of California; Chapman massaged the law. With these partners, Friedlander looked hungrily to the southern valley and the Tulare region. He obtained his land in ethically dubious or outright illegal ways; in the late 1850s, you might’ve seen Friedlander waylaying drunken Tenderloin saloon patroons, plying them with a scheme. Friedlander would ask them to accompany him to the public land office. Land law limited the amount of dispossessed land one person could buy from the state, so Friedlander would slip the man enough money to make a purchase and then immediately buy it back from him once he stumbled out. The next day, you might find Friedlander in his office of the University of California, using his membership on the Board of Regents to privately buy and sell land nominally reserved for public schools. Finally, he’d walk over to the state land surveyor’s office and whisper into the ear of one Isaac Chapman, who just happened to be land lawyer William’s brother. Isaac Chapman would declare some portion of the Tulare basin to be “swamp or marshland,” and Friedlander would use Ralston’s credit to buy it for pennies on the dollar. To hide these spurious land deals, Friedlander and his associates would resell the land in various parcels back and forth to each other, burying the original deal in a mountain of paper in what could only be described as a land-laundering operation. Friedlander came to own 500,000 acres in the Central Valley by the late 1860s.

As Friedlander and his cronies bought and sold land, small-time settlers came to occupy it. These settlers set to work transforming Yokuts land into wheat fields as a method to protect their squatter’s rights. Many of these new settlers were displaced ex-Confederates from the American South. They came to dig irrigation ditches and plant wheat. The ditches were the improvement upon which they could base land claims or be paid for their years of occupation, while the wheat provided the cash infusions they needed every year to keep their farms running. It was these ditches and wheat plants that would eventually suck up water that normally coursed down from the mountains and came to settle in Tulare Lake. The seeds of its destruction were being planted right along Mussel Slough and beside the ghost of Ciau.

In the 1800s, the Southern Pacific

“Bypassed,” Lisa Lee Herrick

railroad drew the maps carving out

land parcels for government pIan the

1800s, the Southern Pacific railroad

drew the maps carving out land parcels

for government possession. In the 2000s,

solid concrete pillars of the California

High-Speed Rail rose from the earth

beside CA-99 like solitary mastodons.

Here, significant ecological transformation was accompanied by continued human tragedy. The land around Mussel Slough had been taken so quickly, so lawlessly, that it was bound in a jumble of conflicting claims. Friedlander and associates, cattle magnate Henry Miller, railroad companies, and squatters all claimed some portion of land and water rights in the area. These overlapping claims created bizarre scenes and comical cat-and-mouse games. Dry farmers who planted wheat were never sure they would hold onto the land long enough to make improvements profitable. Often, they simply stored their grain in whatever structures they managed to build, and slept in tents. Others stored sacks out in the open, praying that the rain would hold. Families formed mutual-aid societies that often took the form of armed vigilante groups roaming the countryside. Railroad agents scoured the countryside serving eviction notices. The families would often hide at their approach so these agents, finding empty houses, would place all the furniture outside and padlock the house. Hiding families returned to break the lock and replace the furniture.

People continued to die for land along Mussel Slough in the 1870s and 1880s. Vigilante groups became more militant. Railroads locked up claims in court battles. The situation escalated until, in 1880, Walter Crow’s shotgun blasts echoed across the Brewer Farm. What only a generation before was a verdant landscape tightly ordered by customary rights was now a landscape of disorder and violence increasingly controlled by a syndicate of conmen and wracked by gang violence.

Are you on unceded indigenous land?

Enter a street address, town, or zip code to see whose.

There was a problem searching for that location.

Learn more — explore the full map.

There are no indigenous nations that correspond to that location; results are most likely for folks in the Americans and Oceania.

Learn more — explore the full map.

Thanks to Native Land Digital for creating and maintaining the map and API that power this tool.

The settlers were not acting in a vacuum. Rather, they operated in a global drama that not only found them agents in an expansionist agenda for the country but tied them to a continent and ocean away. As White settlers transformed Mussel Slough, British factory workers looked hungrily around the world for their own daily bread. Cities like Manchester were simply growing too fast for domestic farmers to feed them. At the same time, Friedlander came to own too much wheat. He had filled his vast estates with tenant farmers who paid their rents in wheat. By the 1860s, Friedlander was holding so much that he could set prices across the entire valley, so much that hungry miners in the Sierra and sailors in San Francisco Bay couldn’t eat it all.

He sought to offload the sullied bounty by chartering ships to take his wheat to whoever would buy it. His first attempt had the ships docking in far-flung settlements around the Pacific: Oregon, Hawaii, the Philippines, Chile. But there was so much that such an ad hoc approach could never sell it all… and the hungry markets of England started to look appealing. Friedlander began traveling every other year to Liverpool to set up business deals for his California wheat. For years, until his death in 1878, Friedlander would send a “grain fleet” of 200 to 400 ships to Liverpool laden with wheat grown alongside Mussel Slough and countless other creeks across the Central Valley.

I am the dark-skinned woman in

“Bypassed,” Lisa Lee Herrick

the fields. I started as a child

so my skin grew dusky and rough

under the blazing sun, peeling

away from me like a lizard’s

tail. My knuckles split from

the alkaline sand, the salted

air stung my lips, and this was

how I watered the ground:

with my body.

By then, the Tulare region — and the larger Central Valley — was one vast field of wheat that stretched from coastal ranges to the Sierra Nevada foothills. Its new shape began to look like the modern world’s epitome of agricultural productivity. Wheat pumped out of the valley in railroad cars and steamship holds where sailors loaded bags of it onto bulky sailing vessels. The wheat would breathe with heat and cold as it crossed the tropics, hitting the Antarctic Cape Horn passage before reentering the tropics and crossing into the North Atlantic. After the 14,000 mile journey, it would enter the gigantic port of Liverpool before being milled into flour and eventually sold to a small baker in downtown Manchester. It was there, sitting on a shelf of a Manchester bakery, that the bread would wait for a tired woman to enter, buy it, and carry it home to her hungry family for dinner. In this journey that would repeat itself thousands of times during the second half of the nineteenth century, Tulare now fed Manchester.

The world Friedlander helped create lived beyond his death. By the 1880s, the Manchester working class family was no longer as hungry as their parents and grandparents had been in the 1840s, but they were just as unhealthy: their new diet was high in energy but nutrient deficient. What’s more, their sapped immune systems had to live surrounded by the digestive tracts of thousands of other people. The global system engendered by developments in California and places like it meant these people found just enough food at regular intervals to finally settle down. The European industrial class no longer had to migrate constantly for food and work; they could simply walk to the corner bakery. Bacterial diseases exploded as human waste flooded inadequate privies and sewers.

Manchester’s eating patterns also helped destroy Tulare Lake. The next century saw an acceleration of the patterns of land use developed around Tulare. White settlement, for instance, accelerated when land titles became clear in the valley, with the best land snatched up before the end of the 1800s. Many new settlers shut out from lucrative valley plots bought land in the foothills — once the center of the Yokuts acorn-based food system. They grazed sheep on grasses between now-untended oak trees. When deep droughts destroyed these animals, some desperate farmers began planting orange trees. By the turn of the century, irrigation ditches snaked across foothills and laced valley bottomland, all feeding plants that would in turn feed humans thousands of miles away. Tulare Lake itself began to buckle under the pressure of so much withdrawal.

When discussing the collapse, my

“The Lights at Red Lake,” Ashleigh BadWolf Thompson

interviewees commented on the dis-

respectful relations fisherpeople

had with the walleye. Because of

greed and exploitation, the fish

disappeared. It wasn’t until we

reinstated respectful relationships

with the walleye that their

population revived.

A new assault came as fishmongers in San Francisco looked hungrily south. The lake sat relatively undisturbed until the spring of 1884. In that year, the Tulare Daily Register reported that “the rivers ran into the lake in a flood that spring and the fish met the fresh water in solid masses. Standing at the mouth of King’s river, one could see a wave come landward, a wave produced by the motion of a mighty army of fish…the ditches of Mussel Slough country were choked by them.” Fishermen swarmed, and the Tulare fishery was dead by the early 1890s.

An irrigation craze swept over the Tulare district toward the end of the century as land titles cleared and global demand for wheat and oranges soared. Farmers began to dream of turning the lake itself into waving fields of wheat, a dream that was growing into reality when the Buena Vista reclamation levee was completed in early 1899. Its builders hoped to repossess thirty thousand acres and seed them all with grain. Soon, cotton, melon, and alfalfa joined wheat to grow on what was once lake bottomland. By the 1920s, over a million bags of grain and fifteen thousand bales of cotton were annually collected from the dead lake.

By the 1920s, over a million bags of grain and fifteen thousand bales of cotton were annually collected from the dead lake.

But by then, Tulare was cut from spring snowmelt and no longer breathing with hydraulic metabolism. It was suffocating. The local paper trumpeted, “Tulare Lake Disappearing: large and fertile farms where lake once stood. Tulare Lake is drying up. Its waters are constantly receding. Like the dawning of a new creation, pleasant groves and fertile fields take the place of its former wastes of waters.” Another paper reported that “Tulare Lake is as dry as a chip. For the first time in recent history, the pelican, geese, ducks, snipes, mud hens… as well as the many fish have found that there is no longer a home for them.” Looking back with quick retrospection in the 1930s, the Fresno Bee wrote that, “The lake has only been a puddle since 1920, having not really existed since 1917 and not having had its customary size since 1906.”

Ecological collapse was everywhere. The disappearance of Ciau and the murder of Yokuts people laid the groundwork for a new world of commodities. It hadn’t happened by chance. Migrating settlers, Friedlander’s crooked land scheme, and wheat purchases by English millers were all predicated on one another. Each decision was made with a fleeting understanding of what was happening elsewhere. Settlers and capitalists often emphasized how they made “improvements” to nature with a seemingly rational design of food economy. But the disappearance of Tulare Lake told another story, one connected to the plight of surviving Yokuts held on reservations. With the deck cleared by mid-century agents, fishermen, irrigators, and levee builders dealt the lake a final blow. In a new, spectral place — these thousands of ghost acres — Tulare Lake traded death for life. The bread that so many relied upon came from the demise of people, of landscape, and of nutrients. Their histories cannot be unbound.

Tulare no longer feeds Manchester, but American and Asian supermarkets. You’ve likely consumed a part of that place. As of 2018, the region is among the nation’s largest producers of dairy products, fruit, and cotton, all grown from generations of genocide, land dispossession, and ecological collapse.

Contrary to what pop culture and

“This Is the Old Way That’s Also the New Way,”

white-washed textbooks would have

you believe, Indigenous people still

exist, and we still know how to pro-

tect and conserve the land. Studies

in recent years are proving this point.

Forestlands protected by Indigenous

communities store one quarter of all

above-ground tropical forest carbon,

or 55 trillion metric tons.

Ruth Hopkins

The Yokuts have witnessed it all; the Tachi Yokuts of the Santa Rosa Rancheria endure in the face of such momentous change. The land — and its ghost lake — occupies a central place in their culture and memory. As tribal historian Raymond Jeff recounts, settlers “killed the whole San Joaquin valley. I’ve never even seen the lake,” he laments, “all I did was read about it.” Importantly, however, the future of this story can be one of rebirth, not death. As the tribe proclaims, “Now, we rebuild. We will endure.”

The ghosts that lie within our shared food history can guide us to the future. Let the water flow. The water will come back, has come back. In the 1930s, persistent floods allowed nesting pelicans to return briefly to the lake; such is but a glimpse of the reanimation that can unfold in erstwhile ghost acres. Part of that restoration must include the Yokuts people and their traditional foodways. The reanimation of ghost acres does not only call for nature preserves or wildlife parks; if our food history played a role arresting complex ecosystems like the Tulare Basin, so too must our eating patterns help reanimate them. Breathing new life into our food system should revolve around restoring indigenous stewardship and decisionmaking over their food landscapes. As ethnobotanist Kat Anderson notes, “the conservation of endangered species and the restoration of historic ecosystems might require the reintroduction of careful human stewardship rather than simple hands-off preservation.” An indigenous management model can not only restore vibrant cultural food landscapes, it can be productive as well. Modern studies are beginning to appreciate that indigenous land management was significantly more productive than originally believed by western science. It is time to use past models and current held knowledge to replace food systems built on genocide and land mining.

The reanimation of ghost acres of Tulare Lake will require policy that acknowledges indigenous claims to land and water, and the academic expertise of ethnobotanists, food historians, agronomists, ecologists — but it should be led by the Yokuts people. Only they have proven adequate to the task of feeding large numbers of people while at the same time storing nutrients for future use. Food is an excellent venue to begin and see through these public-university-community collaborations.

We have the seeds of renewal:

“So, You Have Too Many People to Feed,”

our unikta, sewn into the hems

of our grandmother’s dresses,

carried to new homes, passed by

hand to people with a heart to

nurture soil for them, plant

them and care for them as the

ancestors they are.

Nico Albert

Due to the traumatic history of so many ghost acres, only hard-earned trust and embedded relationships can restore food landscapes that acknowledge past trauma and use indigenous and academic knowledge to reanimate ghost acres into verdant landscapes that will feed us in the future. Truly restorative food justice will use history and dialogue with people like the Yokuts, who still live next to ghost acres held back by irrigation canals, herbicides, and plows. Let the deep wisdom held in place by Yokuts past and present seep into small networks of irrigation canals that water a patchwork landscape of local plants and agricultural plots tended by scientific knowledge. History, restorative ecology, and food culture studies can work together to create just food systems that work within the patterns of place. Only then will the ghost of Tulare Lake truly come alive.

Thomas Finger is Assistant Professor of Environmental History at Northern Arizona University focused on the environmental, economic, and energetic histories of food and water systems, and how communities are bound up in production chains and economic systems. His current book project, Harvesting Power: American Wheat, British Capital, and the Rise of a Global Food System, 1776-1918, examines how American wheat exports became the major tentacle in a global system designed to power European industrialization with cheap food from indigenous and agricultural communities around the world.

Samantha Morales-Johnson always loved art and science, and while earning a B.S. in Marine Biology realized she didn’t have to choose between the two. As an active member of the Gabrieleno Tongva Band of Mission Indians, she strives to honor Creator in all of her artwork and is inspired to teach all audiences about marine life and conservation through engaging animation.

* * *

This essay is excerpted from Acquired Tastes: Stories about the Origins of Modern Food, the latest book in MIT Press’s Food, Health, and the Environment series, edited by Benjamin R. Cohen, Michael S. Kideckel and Anna Zeide. Copyright © 2021.

Used with permission of the publisher, MIT Press.