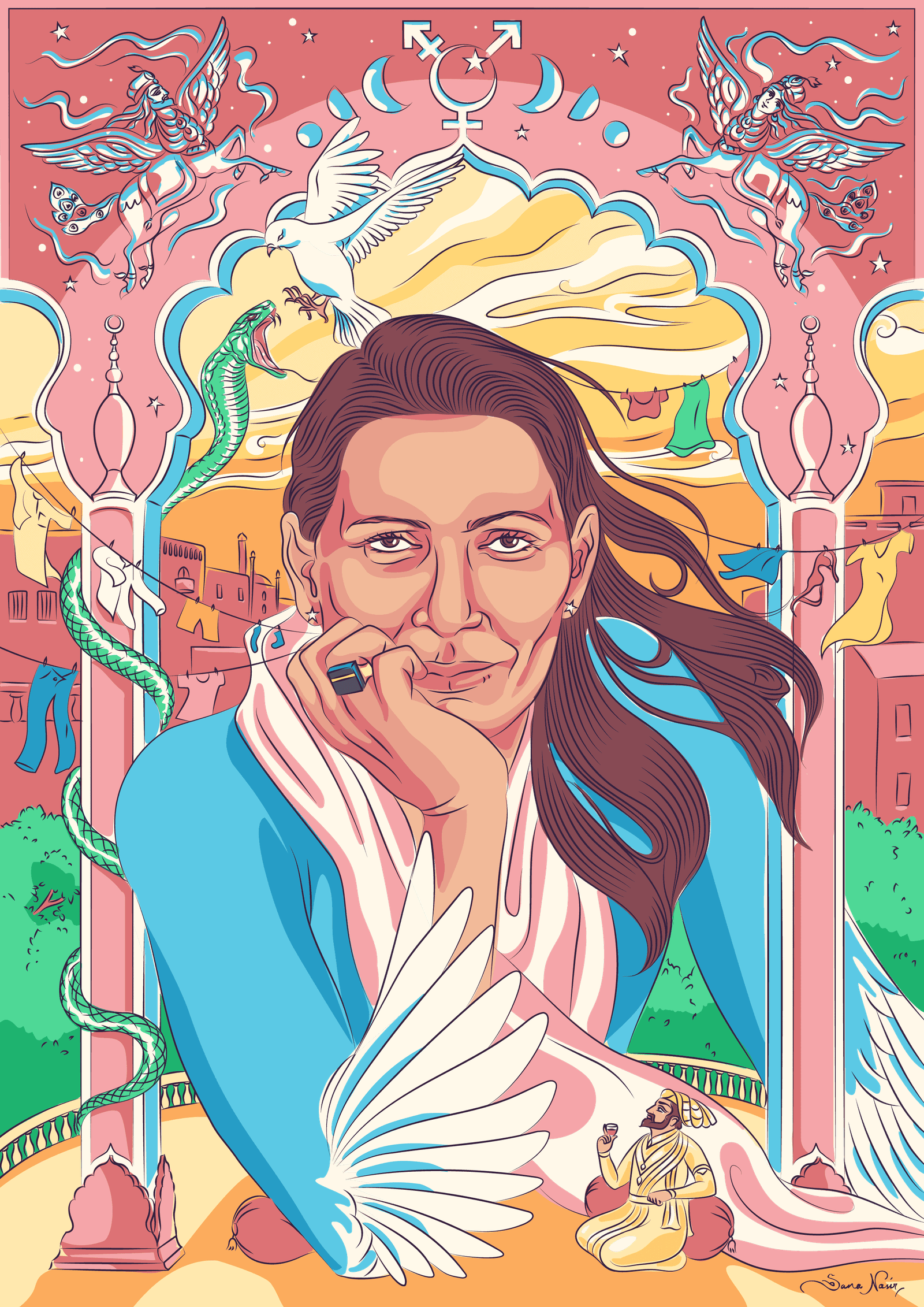

More Than a Portrait

Unpacking the layers of symbolism in no. 7’s featured illustration.

Click the highlighted areas to learn more about the rich detail

artist Sana Nasir wove into her illustration of Bindiya Rana for

Pipe Wrench no. 7’s feature story, The Guru Who Said No.

The emblems of Pakistan — the crescent and five-pointed star, the symbols of Islam depicted on the Pakistani flag — merge with the transgender/gender fluidity symbol, which unites the symbols for female, male, and androgynous people.

The term Buraq is derived from an Arabic adjective meaning “lightening” or “magnificently shining.” In Islamic tradition, a Buraq is a pegasus-like heavenly creature tasked with flying prophets through the seven planes of sky and back without any time passing on Earth. Most significantly, the Buraq transported the prophet Muhammad during the Night Journey, during which he traveled to Jerusalem and then through the seven heavens before returning to Mecca. There was never a sex assigned to the Buraq, nor is there a single, canonical detailed physical description beyond the basic idea of a bridled creature capable of space and time travel. In South Asia the Buraq is seen as inherently feminine and is described as having the head of a woman; further into the Middle East, it becomes androgynous or masculine. This artwork pays homage to both renditions.

Bindyia’s ring is a subtle nod to the Kaaba, the building at the center of Mecca’s Masjid al-Haram, Islam’s most sacred site, and to the story of how she completed her Umrah pilgrimage. Pilgrims walk around the Kaaba seven times in a counterclockwise direction, a ritual known as Tawaf.

The ongoing danger to the transgender community and the community’s resistance are illustrated metaphorically as a dove and a snake.

The dove’s wings are echoed in the design of Bindiya’s sleeves to reinforce her courage and highlight the fight she leads in the battle to eradicate discrimination and violence against the khwaja sirah community.

This Mughal king reminds us of the transgender community’s revered place in the Mughal courts, and of the cultural significance of their stature in the heritage of South Asia. The Mughal Empire lasted from the early 16th to early 18th centuries CE, but transgender identity and culture are documented on the Indian subcontinent as early as the Delhi Sultanate, which began in 1226 CE.

The separate clotheslines in the background hold clothes traditionally worn by women and those traditionally worn by men. Both lines are a part of the landscape, reinforcing the cultural commitment to binary gender and reminding us of the precarious line the khwaja sira community walks.

The colors pink, blue, and white are used in Bindiya’s garments and in the architecture to represent the transgender pride flag.

There are eight details illustrator Sana Nasir wove into her portrait of Bindiya Rama, the main character in our feature story, The Guru Who Said No.

1. The Colors: The colors pink, blue, and white are used in Bindiya’s garments and in the architecture to represent the transgender pride flag.

As designer Monica Helms describes it: “The stripes at the top and bottom are light blue, the traditional color for baby boys. The stripes next to them are pink, the traditional color for baby girls. The stripe in the middle is white, for those who are transitioning or consider themselves having a neutral or undefined gender.”

2. The Dove and Snake: The ongoing danger to the transgender community and the community’s resistance are illustrated metaphorically as a snake attacking a dove, who tries to fend it off. Serpents represent evil or trickery in many cultures, while doves are a symbol of both innocence and goddesses.

3. The Buraq: The term Buraq is derived from an Arabic adjective meaning “lightening” or “magnificently shining.” In Islamic tradition, a Buraq is a pegasus-like heavenly creature tasked with flying prophets through the seven planes of sky and back without any time passing on Earth. Most significantly, the Buraq transported the prophet Muhammad during the Night Journey, during which he traveled to Jerusalem and then through the seven heavens before returning to Mecca.

There was never a sex assigned to the Buraq, nor is there a single, canonical detailed physical description beyond the basic idea of a bridled creature capable of space and time travel. In South Asia the Buraq is seen as inherently feminine and is described as having the head of a woman; further into the Middle East, it becomes androgynous or masculine. This artwork pays homage to both renditions.

4. The Symbols: The emblems of Pakistan — the crescent and five-pointed star, the symbols of Islam depicted on the Pakistani flag — merge with the transgender/gender fluidity symbol. (The transgender symbols merges the symbols for female, male, and androgynous people.)

5. The Laundry: Separate clotheslines in the background hold clothes traditionally worn by women and those traditionally worn by men. Both lines are a part of the landscape, reinforcing the cultural commitment to binary gender and reminding us of the precarious line the khwaja sira community walks.

6. The Ring: Bindyia’s square black ring, worn on her right ring finger, is a subtle nod to the Kaaba, the building at the center of Mecca’s Masjid al-Haram, Islam’s most sacred site, and to the story of how she completed her Umrah pilgrimage. Pilgrims walk around the Kaaba seven times in a counterclockwise direction, a ritual known as Tawaf.

7. The King: A miniature Mughal king, dressed in gold and leaning on a cushion, reminds us of the transgender community’s revered place in the Mughal courts, and of the cultural significance of their stature in the heritage of South Asia. The Mughal Empire lasted from the early 16th to early 18th centuries CE, but transgender identity and culture is documented on the Indian subcontinent as early as the Delhi Sultanate, which began in 1226 CE.

8. The Wings: The dove’s wings are echoed in the design of Bindiya’s sleeves to reinforce her courage and highlight the fight she leads in the battle to eradicate discrimination and violence against the khwaja sirah community.

Sana Nasir is an international award-winning Illustrator and graphic designer. She has worked in the fields of music, art education, publishing, and activism, and spearheads a series of talks “Freelance Ain’t Free.” Nasir resides in Karachi under her artist name, Koi Nahi, and is currently the Art Director for Cape Monze Records and adjunct faculty for illustration at the Indus Valley School of Art & Architecture in Karachi.