Dawood Qureshi

no. 7, The Nonbinary Issue

Summer 2022

Comfort is a strange thing. A word that denotes so much warmth, even in the way it rolls off the tongue, syllables melting into themselves as they are spoken, dripping like warm honey on hot buttered toast.

But it lies. To be comforted is not always to be safe.

Then it all changed. Not all at once. A slippery sliding of small rocks that eventually snowballed into avalanche proportions.

I began to question my identity and gender subconsciously from a young age. I hadn’t the words or the knowledge to explain or label these thoughts as “trans,” but I am so very sure that my dreams of magically transforming body parts and my confusion about my sex, what gender meant for me, and why I couldn’t match what I was told was a “real man,” were attempts to burst through the binary of what I was being told to be. I was trying to rebel, but without the words to do it.

***

I once wrote an article that dealt with the idea of conformity, and called this article “The Art of Belonging;” it explored the idea that humans crave security above most other things — necessary for creativity and reflection — and this manifests through needing to belong. We are then presented with the tribalistic approach that is belonging to a society, an exclusive club we pay a fee to be a part of. The fee is conformity.

To be accepted, to melt into the crowd, to laugh at the same jokes, to understand the same references, to wear the same clothes, to belong; these are the goals of anyone seeking rapport with peers, trying to “fit in.”

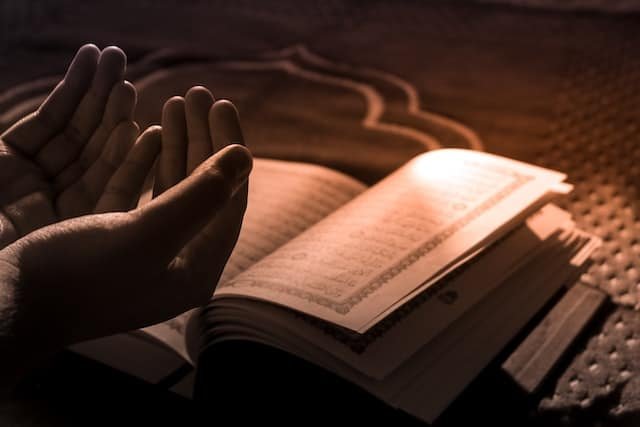

But this is a treacherous kind of comfort that tells us that an environment is good because it is safe. For me, brought up in a strict Muslim household identifying as male, belonging wasn’t a question, and neither was conformity — the rituals of religion and the laws of masculinity drilled a way of being into us; you learn to act a certain way and present a certain way, you are accepted, and you know nothing else and are warned away from ever wanting to.

For British Muslims of foreign backgrounds — in my case, Pakistani and Indian — this is how we ingest our culture. It is fed to us through the lens of religion. It is the only place we are comfortably allowed to explore the roots and spices of our ancestry and non-British identity, albeit packaged and sold to us in a way that tells us how to learn about it and in what way to present it. Culture taught via religion can cross national boundaries and mix and match. I grew up seeing traditional Pakistani and Indian clothing, eating food and listening to music that brushed against Arab and Middle Eastern countries. It was here that I obtained my understanding of my culture, and only here that I saw it paraded proudly when other parts of society vilified it.

This is the promise I was given by my religion, by my community, and by the guides and leaders of that community: I would find great solace and calm in the carpeted, perfumed hallways of mosques, in cross-legged meditations in beautiful prayer chambers.

I learned to be proud of my culture, but only as a Muslim. And so it was that I only had one way to fully access it, so that when I lost access to the religion I lost the culture as well.

Transness and gender have always been tricky topics to broach in Islamic settings. Tricky because, as a system and mainstream religion, Islam has become accustomed to a set of conservative practices that disallow most from questioning and reflecting on their identity in this fashion. Queerness is so terribly misunderstood and so hated that any whiff of otherness from stereotypical Muslim men and women is cause for a putdown, at best, or expulsion from the community at worst. I learned that my culture was a straight and cis-gendered thing, fit for those at home in the binary, and so when I came out as gay, then queer, then nonbinary, and eventually a trans nonbinary woman, I felt I had pushed myself so far from this that I was no longer worthy of my culture.

Coupled with the colonial white-washing of queerness in the places from which my family comes, I was at a loss; I was not white or English and craved a connection to the brown that covered my body, but the only way I knew how to access my culture was via a religion that didn’t want anything to do with me.

My comfort had lied to me. My safe space was only comfortable because I had no knowledge of anything beyond it. I came to an understanding then: the tools I had been given to access the culture I needed to “belong” no longer felt available to me. I hadn’t those tools any longer.

***

This is sadly the case for many trans Pakistani and Indian Muslims in Britain, and trans people of color who are Muslim or have Muslim backgrounds more generally. We are searching for a way to understand and reclaim our cultures as they once were — many had a better understanding of identities and gender before colonialism poisoned them — but can feel othered by the grip religion has on them and us. I now explore my culture in my own way, through what I find validating and euphoric, and through the words of a growing number of South Asian trans activists and campaigners who seek to enlighten from an unpoisoned, decolonial position.

So go ahead. Get comfortable… and we can begin.

Dawood Qureshi (they/she) is a queer writer, journalist, and wildlife filmmaker; a researcher at BBC Natural History Unit and BBC Earth; an Ambassador for the Bumblebee Conservation Trust; and an Engagement Officer for the youth-led nature organization A Focus On Nature. They are absurdly passionate about wildlife, conservation, and the environment and can usually be found on the coast combing for marine life, exploring the ruins and new builds of our urban jungles, and speaking and writing far too much about insects and arthropods.

previous

my pronouns are super/nova

Taté and Ohíya Walker

next

I Could Have Been a Doctor

Soraya Roberts