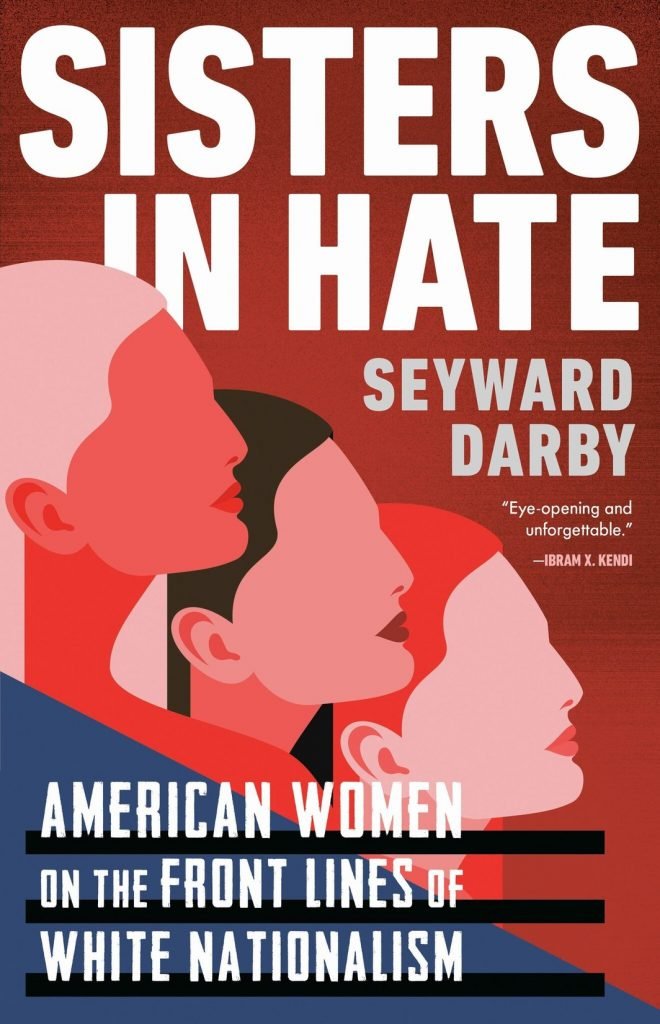

Veering Right:

An Excerpt from “Sisters in Hate”

Seyward Darby || April/May 2021

What happens when Nice White Folks get radicalized? Not in the direction of racial justice, joining arms with their BIPOC neighbors — the other way.

I’ve spent several years researching people, particularly women, who have undergone exactly this transformation; who in the face of national upheaval, unease, and uncertainty have become vocal white nationalists. No two people’s stories are the same, but they all seem to start in a state of weakness forged, paradoxically, by power. “White people had not developed the constitution for forbearance,” Mason-Campbell writes. “Brazenly detached, unapologetically fragile, and woefully in denial, Whiteness outsourced culpability, and along with it critical lessons in resilience and character.”

Because they are uncomfortable, we are wrong.

They want to have more than everyone else; it

makes them feel safe and powerful. They want

an unfair advantage. They deeply believe in rank,

and status requires that someone be below you

when you look down.

“Seeing in the Dark,” Breai Mason-Campbell

When faced with challenges that, whether real or perceived, are often overstated, the people whose trajectories I’ve followed seek a narrative to explain what’s happening. When they encounter white nationalism-as-narrative, it performs a neat trick: It validates their sense of grievance, and then transmutes it into a lofty purpose. White nationalism provides acolytes with adversaries and comrades— targets at which to fire their blame and friends to cheer them on as they do. It asks remarkably little of believers while feeding them the lie that they’re doing the most. And history shows that this approach can work, to terrifying effect. “Take it from me,” Gertrud Scholtz-Klinck, the highest-ranking woman in Nazi Germany, said in an unapologetic 1981 interview, “you have to reach them where their lives are — endorse their decisions, praise their accomplishments.”

This is a longer conversation.

Help Pipe Wrench create more space for reflection.

What follows is an excerpt from my book, Sisters in Hate. To set the stage, Red Ice is a media company that produces audio and video content peddling white nationalism. It is run by a husband and wife team, Henrik Palmgren and Lana Lokteff. Lana, the more famous of the two, cut her teeth as a pundit of the “alt-right”— the name that, for a time, white nationalists slapped on their cause to make it seem like they weren’t promoting the same agenda as the Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, and other forebears. Over the years, through her program Radio 3Fourteen, she has amassed a constellation of like-minded women, some of whom she’s played an important role in radicalizing. They’ve found solidarity in bigotry and menace, veiled by lipsticked smiles. They’re all Nice White Folks who veered right and never looked back.

***

Pretty white girls get a bad rap—that was the consensus of a klatch of women Lana assembled for an April 2017 Google Hangout that she streamed for Red Ice viewers. The rap is particularly bad in pop culture. Take Regina George, the villain of the iconic comedy film Mean Girls, played to vicious perfection by actress Rachel McAdams. She manipulates her friends and cheats on her boyfriend. She creates an insult-filled “burn book” that almost tears her high school apart. But it didn’t have to be that way. Regina George didn’t have to be mean, beautiful, and white. Hollywood made her that way, Lana insisted. “The evil girl in school is always the pretty blond girl. She’s the bad one, she’s the bitchy one,” Lana said. “It’s the mixed-race or the multicultural or the leftie ugly girl with her little cat glasses and purple hair that are the good ones.”

The “war on beauty,” as Lana described it, was a leftist conspiracy targeting women like the guests who’d joined her that day. Each of their faces filled an on-screen box in the Google Hangout. One was Brittany Nelson (a.k.a. Bre Faucheux), a far-right vlogger and fantasy fiction writer. Nelson agreed that Mean Girls had an agenda. “The girls who got along and hailed themselves as being good people, they were outcasts,” she said. Like the one with “raccoon eyeliner”— Nelson dragged two fingers around the edges of each of her eyes to demonstrate the repugnant thickness—and “goth hair.” (Fans of the movie will remember this as actress Lizzy Caplan’s character, Janis.)

Lana had plucked Nelson out of relative internet obscurity. A Louisiana native, Nelson once dabbled in beauty blogging, reviewing lipsticks and nail polishes on her website Tribal Faerie, while working toward a master’s degree in the United Kingdom. She was a petite brunette who sometimes went red, with a husky voice and a fondness for pearls. “Women who like to look nice (like myself ) should not be berated for it,” she wrote in a 2013 blog post. “Just because I take time to get ready in the morning doesn’t make me dumb, or unintelligent, or into myself. It means I like things that are shiny and sparkly!!” The Twitter feed she kept back then was a stream of random thoughts on school, dating, hitting daily word counts, and smoothie ingredients. There were also photos of her dogs and personal responses to tweets posted by celebrities, including comedian Kathy Griffin and figure skater Johnny Weir. Nelson expressed support for LGBTQ rights and cheered The View’s Joy Behar for challenging conservative Christian pundit Pat Robertson on social media.

When they make questionable decisions,

it’s because the situation is difficult, i.e.,

“The Opioid Epidemic” or the need for

financial support during a pandemic.

When Black people make questionable

decisions in a similar set of circumstances,

it’s because we are morally deficient, i.e.,

“Crack Heads” and “Welfare Queens.”

Unwillingness to admit to this belief in

their superiority keeps us trapped between

the rock of violent, insurgent white supremacy,

and the hard place of liberal denial.

“Seeing in the Dark,” Breai Mason-Campbell

When she came back to the United States after graduate school, Nelson lived at home and looked for work. Complaining about being in close quarters with her mom, Nelson tweeted, “I need a job! Get me outta here!!” But she couldn’t find a gig. In a blog post, she recounted telling a friend, I can’t support myself without help from my parents….I had fifteen job interviews and they all said I don’t have enough f*cking “experience.” Her friend replied, That’s our whole generation. No one is doing good on any of those things right now. In another post, Nelson said that she’d been “lied to” about what success would require. “When I first got out of school, everyone told me that if you go to college, you will get a job. And if you get a Masters (which I did), you are guaranteed an even better job or a promotion down the road. Well, that’s just not true anymore,” she wrote. “Now, with the influx of degrees, a piece of paper saying you studied at Uni doesn’t mean shit because tons of other people have the same thing.”

In her free time, Nelson worked on her fiction as much as she could and sent out query letter after query letter. Nothing stuck. “Got my first representation rejection in less than 24 hours!” she tweeted in 2013. A few weeks later: “I am beginning to think that all these ‘How to Write a Great Query Letter’ sites overall encompass that agents don’t know what they want!!” She decided to self-publish her first novel, The Elder Origins, described on Amazon as “a historical fantasy with sinister blends of medieval warfare, young love, Native American legend, and vampire lore that will excite anyone with a taste for the macabre and alternate versions of history.” Nelson later wrote that she loved being able to set her own deadlines and expectations for her work but resented the “stigma” that self-publishing carried. Why did people feel like they had license to criticize her grammar, even though they knew she didn’t have an editor?

Nelson built a profile on BookTube, a YouTube subculture in which users videotape themselves reviewing books. Her taste ran the gamut, from The Hunger Games to the Pulitzer Prize–winning All the Light We Cannot See, though she knocked the latter for having young “protagonists who don’t protag.” Nelson soon found that the digital book community could be off-putting. “People are selfish when story lines don’t go their way,” she once said of online reviewers. “Whatever happened to going along the ride that the author takes you on?? Rather than getting angry about what YOU want to happen.” She resented readers telling her how to write. “[I] might never be a best selling author. I might not be a New York Times Best Selling author. [I] might never reach the income I want to from my writing. And I certainly won’t be everyone’s flavor when it comes to my stories,” she wrote in November 2015. “But saying that there is a ‘proper’ or ‘correct’ way to write puts a really nasty taste in my mouth.”

We struggle to grant others the same grace we grant

to those with whom we relate. At its biological roots,

it’s a defense mechanism, a way for small groups to

protect themselves from outsiders.

“The Questions That Opened Me Up,” Kristina Daniele

By the following summer, her tone had grown markedly more bitter, and her politics seemed to be sliding to the right. She posted “Unpopular Opinions,” a video in which she described giving up on feminism because it had been “hijacked by a bunch of freaking nut bags.” Several weeks later, she wrote about what she saw as publishing’s fixation on diversity—white writers were called racist if they didn’t have diverse characters and were accused of cultural appropriation if they did. It was a Catch-22, and to what end? “Every single culture in existence has resisted diversity by means of killing each other, segregating against one another, and saying it was even immoral to even be around one another,” Nelson said in defense of books with only white characters. “Taking comfort in one’s own ethnic group or race is not racist.”

The video got thousands of views within a week. Many other BookTubers were furious; some recorded video responses saying as much. But when Lana saw the video, it piqued her interest. She invited Nelson on Radio 3Fourteen, where Nelson said “pure anger” had inspired her anti-diversity tirade. She claimed that, in college, when she’d suggested that the curriculum judged “white civilization” more harshly than others, she was accused of being ethnocentric. Lana chuckled knowingly. “It’s only wrong when whites do it, right?” she asked.

“How dare you?” Nelson shot back in mock horror. “Check your white privilege.”

After her appearance on Radio 3Fourteen, Nelson made a personal video expressing her devotion to the far right. For several months, she’d been reading blogs and watching videos that excoriated feminism, liberalism, and diversity. Recognizing the purported evils wrought by the left—“the collapse in national identity, the destruction of the nuclear family…and the very real threat of white genocide”—had left her despondent. “I couldn’t even go to the mall to buy myself a pair of jeans,” she said, “without noticing the trends that I had been reading about taking place all around me.” Nelson had felt alone in her despair until she went on Radio 3Fourteen. Talking with Lana had been like “taking in an entire glass of water after months and months of chronic thirst,” Nelson said. She’d lost friends as a result of her political coming-out, but no matter: “My days of engaging in white guilt are over.”

By the time Nelson appeared in the Google Hangout with Lana a few months later, she had set book reviewing aside. Her YouTube bio read, “Conservative. Traditionalist. #AltRight Enthusiast. American Nationalist. Pro Gun. Anti-Left. Right Wing Blogger. Author. YouTuber. Completely Deplorable.” Nelson was aspiring to be what Lana described in the Hangout as “the ideal alt-right woman”—she “has a good relationship, she keeps a little fashy household, but she’s also fighting back.” Sure, it could be hard work for a smart white woman to record a video or bang out a few tweets each day, especially if there were kids and a husband to take care of (as there should be). Yet a woman with the skill to juggle obligations and the toughness to withstand naysayers “needs to take time to do battle,” Lana said, “against anti-white politics.” Racist women could have it all.

Within a few months, Nelson would launch a YouTube channel that she called 27Crows Radio and become the cohost of the podcast This Week on the Alt-Right. She started a romantic relationship: Lana set her up with an alt-right believer who lived in the same city that Nelson did. They exchanged messages on Twitter and agreed to meet. After he watched her on Red Ice, the prospective beau told Nelson that he wanted to buy her dinner. On their first Valentine’s Day together, he gave her the biggest bunch of roses she’d ever seen.

She stood in her full glory and proudly beheld

the beautiful world of her making.

“The Rose’s Winter Dream,” Fergal Mc Nally

Another guest in the Red Ice Google Hangout was Rebecca Hargraves (a.k.a. Blonde in the Belly of the Beast), a vlogger in the “liberal, fascist hellscape” of Seattle who sometimes recorded videos with a photographed backdrop of vibrant pink and white flowers. She’d first appeared on Radio 3Fourteen in early 2016, soon after she started a YouTube channel with a video titled “Living in Libtard USA.” She followed that up with “Feminism Is for Idiots and Uglies.” She presented herself as the antithesis of what she abhorred: Hargraves wore carefully applied makeup, with tasteful black lines drawn around her eyes, mascara applied to her lashes, and pink gloss smoothed on her lips.

Hargraves had grown up in a largely white and Asian suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, where black students were bused into her district for middle school. “They were often from broken homes, they were interested in crime, disinterested in academics, they were highly sexualized from an extremely young age,” she once said in a video. “My friend was successful because her black family moved her out of a black neighborhood and taught her to adopt the values of the white community.” After graduating from the University of Missouri, Hargraves worked in finance in New York City, but by age twenty-three, she saw the endgame of the corporate life that she believed feminism had pushed on her: She’d be a slave to her job and either not have kids or be an absent mother.

Hargraves decided to move to the West Coast to reevaluate her life; she ate healthily, stopped drinking alcohol, and decided that she’d been too dominant in her romantic relationships. She also had encounters she didn’t like with people of color—for instance, an Uber driver in a niqab who wouldn’t let her get in the car with the pet Chihuahua that she carried around in a bag. A man she went out with briefly broke up with her in a text that said, I cannot date you anymore because I do not believe that you will teach our children that all cultures are equal and to love everyone equally. “He was right,” Hargraves told her YouTube viewers. “I’m absolutely not going to teach my children that—that’s garbage.”

She became an online pundit because she felt like she couldn’t speak her mind among friends and acquaintances. “I feel like I need to discuss these things or I’ll lose my mind,” she told Lana in their first conversation. Lana sympathized: “It’s amazing how much hate you can come up against with these liberals.” Hargraves agreed. “It’s a huge double standard,” she said.

The exchange fit neatly into a rubric that Lana had described to me. When selling white nationalism to other women, she explained, it was important to focus on “the really simple double standards.” Simple, I suppose, in the sense that they were tapered to the point of falsehood, or premised on inaccurate statistics, or derived from personal anecdotes instead of rigorous study. “Girlfriends don’t go out and have drinks and talk politics like this,” Lana said, again referring to the conversation she and I were having. “But I notice when I’m in a group of normie girls, if you will, and I just start asking questions, present some of the alt-right topics, a lot of them respond.”

The subtext seemed to be that women were dumb and malleable. Lana would never have said that outright. When it came to recruitment, she preferred serving up compliments to shaming. She told women that their blond hair and blue eyes—or, if they didn’t have those traits, their white skin—were rare and enviable. “A lot of these white girls are tired of being told that white is boring, white is common, white is not diverse,” she told me. If flattery didn’t work, Lana tried other techniques. She asked women: Wasn’t it terrible that the mainstream media attacked “average housewives”? Weren’t they worried about the dearth of alpha men in liberal circles? Surely they yearned for racial sisterhood, like what black and Jewish women had. All of those suggestions, Lana told me, might push white women her way—into white nationalism.

Nice White Folks have not truly let go of the belief

that this is a mess of Black people’s own making.

Not seeing the team of dolls trapping me in my

place enables the illusion of meritocracy: White

people are doing better, it is easy to believe,

because they are just more organized and make

better choices. It is really sad, Nice White Folks

might say, that Black communities are so broken.

That there is so much poverty and crime, but they

are doing it to themselves. They shoot each other.

They sell the drugs.

“Seeing in the Dark,” Breai Mason-Campbell

Another option for recruitment was outright fearmongering. “There’s a joke in the alt-right: How do you red-pill someone? Have them live in a diverse neighborhood for a while,” Lana told me. If women did that, they’d understand. “Women are scared of rape,” Lana continued. “They’re scared of crime.”

She once made a similar point in conversation with Hargraves, asserting that America’s more diverse areas supported Trump while heavily white ones tended to support “communist” or “cuckservative” candidates. Hargraves attributed this supposed trend to “the luxury of being in the elite. There’s not a lot of intermingling with low socio-economic backgrounds. They don’t really see a lot of the problems that diversity does cause.” Neither woman cited statistics. But figures were available, and they proved the assertions wrong. During the 2016 primary season, a New York Times analysis of U.S. counties found that “one of the strongest predictors of Trump support is the proportion of the population that is native-born. Relatively few people in the places where Trump is strong are immigrants.” The findings held fast through the election: Cities with larger shares of white voters went for Trump. Generally, the less white a county’s population, the more heavily it opposed him.

The far right has always appealed to feeling, not fact. It conflates personal experience with hard evidence, and it inflates acolytes’ sense of self. “A lot of these liberal women, they’re not risk-takers, even though they have piercings or blue hair,” Lana once said. “What we do, the things we talk about, I don’t think it can get any more high-risk.” Her statement underscored white nationalists’ quest to be seen as rebels for a righteous cause. Lana presented the mission to reverse decades of progressive change as simultaneously common sense and insightful; rational and radical.

The subtler effect of her orchestration—particularly bringing far-right women together in conversation—was to assure female viewers that ideas wider society might deem offensive feel normal if you’re in the right crowd. “It’s okay to think like us,” Lana said. “If you do, there’s a whole tribe here that you can join of girls that actually have your back.”

When Erica Alduino, a key organizer of the Unite the Right event in Charlottesville, joined Lana for an episode, they both criticized a black female protester at a speech Richard Spencer had recently delivered. The woman wouldn’t give up the microphone until Spencer answered her question, which was “Do you think that you are better than I am?” Lana said the protester reminded her of “gangsters…in the ghetto” who “size each other up.” Alduino lamented, “That’s part of their culture, though.”

When Florida schoolteacher Dayanna Volitich (a.k.a. Tiana Dalichov) was exposed as a far-right podcaster and lost her job—not long after Lana was a guest on Volitich’s program, Unapologetic—Lana declared it an abomination. “Two girls…do a simple podcast, just talking about leftism and how we need to take the schools back, [and it’s] national news!” she said in a Red Ice video. Ayla got involved too, videotaping herself calling the school that had fired Volitich and leaving a message for the administration condemning its decision.

When tradwife Sarah Dye (a.k.a. Volkmom) was identified as part of Identity Evropa, with ties to a member who had painted swastikas on an Indiana synagogue, protesters appeared at a stand she and her husband operated at a local farmer’s market. Lana invited Dye on Radio 3Fourteen, where she praised her guest for being “brave” and described white nationalists as “gracious” and “well-rounded.” Lana also showed clips of “trashy” protesters and laughed at them. “We’re dealing with sick people,” she said, “and we need to treat them that way.”

In Under the Banner of Heaven, Jon Krakauer writes of the individual who becomes a fanatic, “A delicious rage quickens his pulse, fueled by the sins and shortcomings of lesser mortals, who are soiling the world wherever he looks.” Replace “him/he” with “her/she” and the quote applies to much of Radio 3Fourteen’s programming. Lana and her female guests made it their business to remind viewers that they were better than anyone who opposed their movement—intellectually, spiritually, and genetically. And should an adversary come after one of their own, they would degrade them mercilessly.

Seyward Darby is the editor in chief of The Atavist Magazine and the author of Sisters in Hate: American Women on the Front Lines of White Nationalism.