The Third Pig

Breai Mason-Campbell || June/July 2021

I will say to the CREATOR,

“My refuge and my fortress, my God, in whom I trust.”

Psalm 91:2

We don’t blame the wolf. His behavior is part of the lay of the land, and expected. We blame the pigs. I stared down at LaDon, blaming him. He was quiet, flanked by posters chronicling the steps to his untimely demise. To the left of the casket was a montage of images, one more irreverent than the next. Corner Boys with blunts flaunted $100 bills, fanned out to display a small fortune. To the right, he leaned on a Mercedes, money trophy in hand, his nickname, “Hella Paid,” in script across the bumper.

The baby face I had last seen now had sideburns and a short beard covering the sculpted cheeks and chin of a young man who would never grow old. A black stocking cap hid the place where his skull had been hollowed by the bullet; a slideshow of photos on the screen in the corner of the room reminded me that I knew him when he was too little to tie his own shoes.

We don’t blame the wolf. His behavior is part of the lay of the land, and expected. We blame the pigs.

After 19 years of working for racial justice and educational equity in Baltimore, animated memorial services for my former students had become a seasonal experience. Rather than gospel, there was Trap music playing. The weed smoke and alcohol were ubiquitous to grief, as were the R.I.P. t-shirts, today’s emblazoned with LaDon’s defiant image, holding two middle fingers in the air. Charm City’s sackcloth and ashes.

All of this dug right under the skin of my Talented Tenth, Racial Uplift sensibilities. Despite my burning desire not to be a Hotep, I made a mental list of objections ranging in condemnation from “Tacky,” and “Are you fucking serious!” to “The reason this happened in the first place.” I fumbled through the dark recesses of my shame hoping to yank up from the root what I knew to be a problematic, “blame the victim” ideology. Sandtown was, after all, a house of straw, and LaDon was born there.

The late 1960s also marked the FBI and

LAPD’s destruction of the Black Panther

presence in Los Angeles, a group that had

created opportunities for status and community

centered on activism for Black Angelenos.

Gangs filled the void. The Cribs, better known

now as the Crips, most likely formed at Fremont

High School in southern Los Angeles in 1969,

followed by the Bloods at Centennial High School

in Compton shortly after.

“If We Can Soar,” Shanna B. Tiayon

In the fairy tale, the third pig let his brothers in without talking shit. He didn’t, “I told you so,” or trash talk. He just opened the door because wolves are dangerous and we all deserve safety, and all three lived to fight another day.

LaDon’s murder marked 25 years of having spent my life fighting a baffling tenacity of violence and death in my hometown, and I still could not find a place where he could have gone for refuge. We had become casual over the years. The Corner has become such a standard aspect of life for city Black folk; we have accepted it. We hope our youth won’t stay too long, and that it won’t kill them while they try it out, but not loving them for trying it is off the table. Too many of them are trying it.

Now, there were “Dearly Departed” dog tags and “In memoriam” tattoos. “You’ll be Missed” and “Gone, But Not Forgotten” hoodies. This was a celebration of LaDon’s life. The good, the bad, and the ugly. There was no criticism or remorse or regret. He sold drugs. He smoked weed. He threw up signs. And, what? Kids make mistakes. Should the price of youth be so high? He was a kid. No wonder his wake looked like a festival.

LaDon’s grandmother nestled her arm and shoulder into the folds of satin that would be his shroud, preparing to tuck him into bed for the last time. She seemed to be memorizing every line of his face looking for the answer: Why? What did I do wrong? What could I have done differently? Who was he? Who am I? She called her sister over to help her untangle the knot of unknowable questions. They stared, contemplating the past and imagining a future that would never come.

* * *

I vote democratically. I stand up against Bootstraps thinking and policies. I understand the impact of poverty, institutionalized racism, and generational trauma. And I still judge people. My therapist and I have talked about how deeply ingrained Just World Fallacy is for me. I filter every moment — this funeral — through a moral compass that says you can fix it if you work hard enough.

Just like birds, just like all animals:

so many of us don’t have the people

we need, the places we need, anything

we need, to prosper the way we should.

And (No) Birds Sing,” Soraya Roberts

Why is LaDon dead? Was he the first little pig, lazy and foolish? Did he make bad decisions and have to sleep in the bed he made? “Pound that straw into bricks, like the Isrealites did!” my brain says. “The raw materials for our liberation are at our fingertips!” But then I remember that white skin, generational wealth, and police protection are essential ingredients for any mortar that can take the heat in this country, and I begin to cry.

* * *

When I was 17, my boyfriend, R., was shot in the head and killed. I was away at college, and he was back in Baltimore. Though my life’s work has consequently been devoted to dismantling the system that keeps digging graves for Black boys, I have been quietly passing judgment on R. these 26 years, until I attempted to build a brick house for my own children.

After taking every class I could about the causes of poverty, desperate to fix it, I moved home, unwilling to turn my back on the youth and communities here as a lost cause. I chose to have a family and raise kids in Baltimore. Grit would make it possible. The next generation of Rs would have a chance at survival if, through my work, I could just get them to change their behavior.

But then I remember that white skin, generational wealth, and police protection are essential ingredients for any mortar that can take the heat in this country, and I begin to cry.

I did all the right things. I bought a house near an integrated school with a high rating. My mortgage was as large as I could afford. By the time my son was in middle school, his classes were segregated, his White peers having been moved to the high ground of private schools and Advanced Academics programs. Worse, to my horror, a group of drug dealers had the same budget for homebuying as I did. Housing prices start around $650K in the neighborhoods with private security, parks, and a conspicuous absence of corner activity. We go there for picnics and see the privileged laughing with their Great Danes and charcuterie plates.

Outside those spaces, structural inequality

ground on, begetting pain and violence.

Refuge, as ever, is temporary.

“If We Can Soar,” Shanna B. Tiayon

Pharaoh said to make bricks without straw. The Black community has been asked to hold bricks together without mortar — to get better with sheer will with no equality, no transference of wealth or opportunity, no time off from racist terrorism to heal. Without the binding sealant of white power, my bricks could not keep our the elements. Despite my best efforts, I had, with the rest of Black Baltimore, been corralled into an oubliette, where the road to freedom was visible but not attainable.

R ‘s mom had built a straw house with his father. She was a teacher. He was an addict who seemed to be in no way helping with the project to get R. on the right path. Her first move to the refuge of suburbia, to Woodlawn where we grew up, turned out to be a house of sticks. When R. got into fights at our high school and was expelled, she moved further into the suburbs in an attempt to separate him from the people and conditions that were dragging him down. Randallstown, or “Randalsclown” as R. called it, because it was miles from the call of the city and so disconnected from the world he found important, was to be a fortress, solid brick. It didn’t hold.

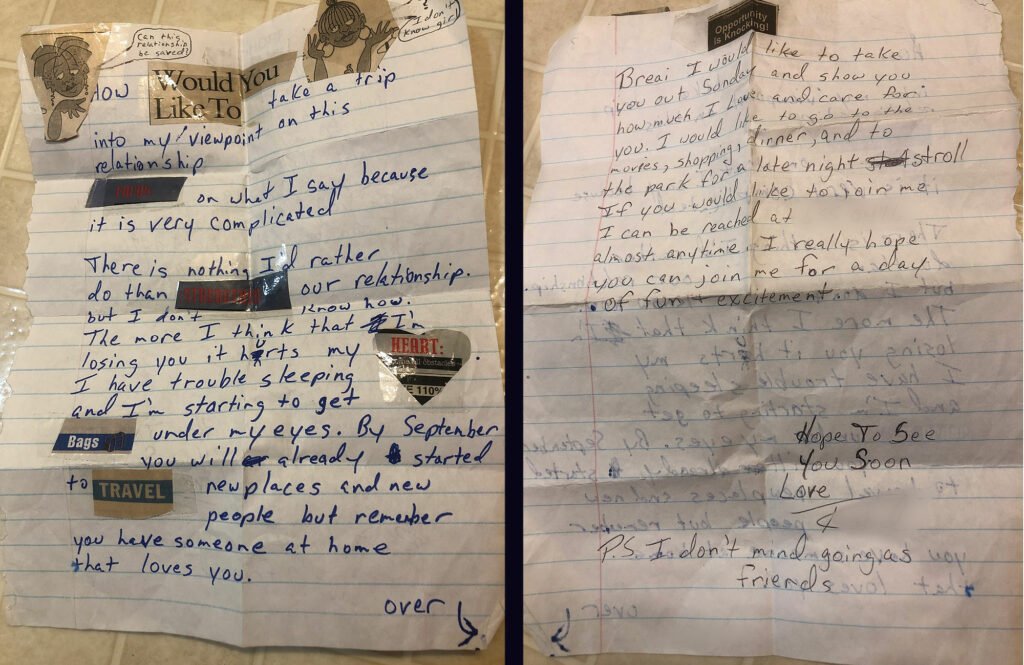

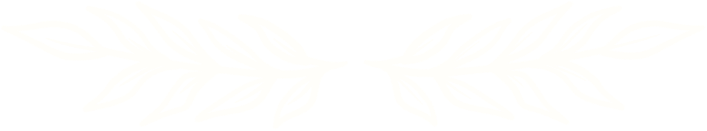

My daughter found a letter from R. tucked into my high school memories book.

I think of my father’s multiple car

repossessions (including the

minivan and a car he “bought” for

me) and how he never lived under

a roof that didn’t belong to my

grandparents or a woman, and I

wonder what kind of father he could

have been if he’d been successful at

something. Or if he could’ve practiced

caring on some birds, or had space to

be creative and feel in control, part of

a community?

“Snap,” Deesha Philyaw

For these 26 years, I have been remembering him as someone who didn’t want much. He wasn’t going to college. He was hanging out with the wrong people and divided his time equally between smoking weed and selling it. He made a decision to be the first pig.

I have no memory of having read this letter 26 years ago. Reading it was like seeing it for the first time, ever. I saw creativity and tenderness, humor and intellect. He was smart and eloquent and hopeful… and dead. The day I left for college — the last day I ever saw him — we stood in the dining room of my mother’s house, lights dimmed, his white van parked out front. He hung his head as he handed me a gold ring. He said that I was going to “meet some college nigga” and forget all about him. He said that some lawyer or doctor was going to replace him. He told me how much he loved me.

* * *

It was LaDon laying in the casket, but for me, it was R. It was always R. Faced with the impossible task of making bricks without straw, he built a refuge of smoke, and jokes, and fists, and love. It could not keep out the wolves. The space between a refuge and a fortress seems insurmountable. No wonder so many perish in the gulf, burned by the fiery arrows of derision shooting from our eyes.

Breai Michele Mason-Campbell is a Baltimore native, community activist, teacher, dancer, and kinetic storyteller. A Harvard graduate, Breai Michele is the founder of Moving History, an arts-integrated dance curriculum that teaches students and communities about the contributions of African Americans to American history through movement. Her work has been supported by grants from Teaching Tolerance, the Frankie Manning Foundation, and the Baltimore Children and Youth Fund, which supported Moving History’s efforts to bring racial equity to education with a $179,000 grant in 2018, and another in 2019. She’s the proud mother of three.

Her last contribution to Pipe Wrench was April 2021’s feature, “Seeing in the Dark.”