Luvia Lazo

no. 7, The Nonbinary Issue

Summer 2022

Return to Juchitán

Mexico’s muxes have been media darlings lately, but not every image and story make it into Vogue.

After 15 years I returned to Juchitán de Zaragoza, and it is just as I remember it: chaotic, noisy, crowded with tuk-tuks and cars.

The first time I went to Juchitán I went as a photographer’s assistant to take photos of the muxes, documenting the lives of Mexico’s third gender. “Muxe” (moo-SHAY) is a faulty pronunciation of the Spanish word for woman, “mujer,” used in a derogatory way to call a man cowardly or gay. It has now been reclaimed by the LGBT community: The muxes, Indigenous Zapotec people assigned male at birth but who identify as women and/or have a traditionally feminine presentation, use it to refer to themselves proudly after many years of hard work to change its meaning.

Their story has been shown from the outside, surrounded by glamour and happiness, but the story is very different for the people living it.

Like the first time I went to Juchitán, I went to a Vela Muxe — a party celebrating muxe identity. Unlike the first time, I didn’t take pictures. It’s a space that belongs to them and where they can be completely free; they dance and dress as glamorously as they like, and that is no longer something I want to exploit. Googling “muxes” will lead you to more than enough images.

On the way there I remembered a play by Héctor Flores Komatsu, Andares, in which a muxe character says: “If there is poverty, let’s not show that.” I’ve always seen luxury and elegance in muxes, and for a long time I didn’t know the other side of the myth. The play is based on real-life stories and Alex, one of the characters, lives very close to Juchitán, so I decided to visit her.

I met with Alex and heard stories of pain that have not changed for 15 years: We are still fighting for our spaces. We seek safety, so that our voices can continue to be heard. We continue to disappear, dying by “natural” causes or “suicide.” Men in these lands can have all the women they want, she says, but also a muxe — and she is often abused. “People want our work, our creations,” Alex says, “ but they don’t want us to love and be loved.”

What I share are images taken with the greatest care of the humans who are muxes, who work every day to survive and live and re-live in their land. Their way of existing in the muxe land; their way of working; the life behind the Vogue glamour, television programs, editorial photos, and media.

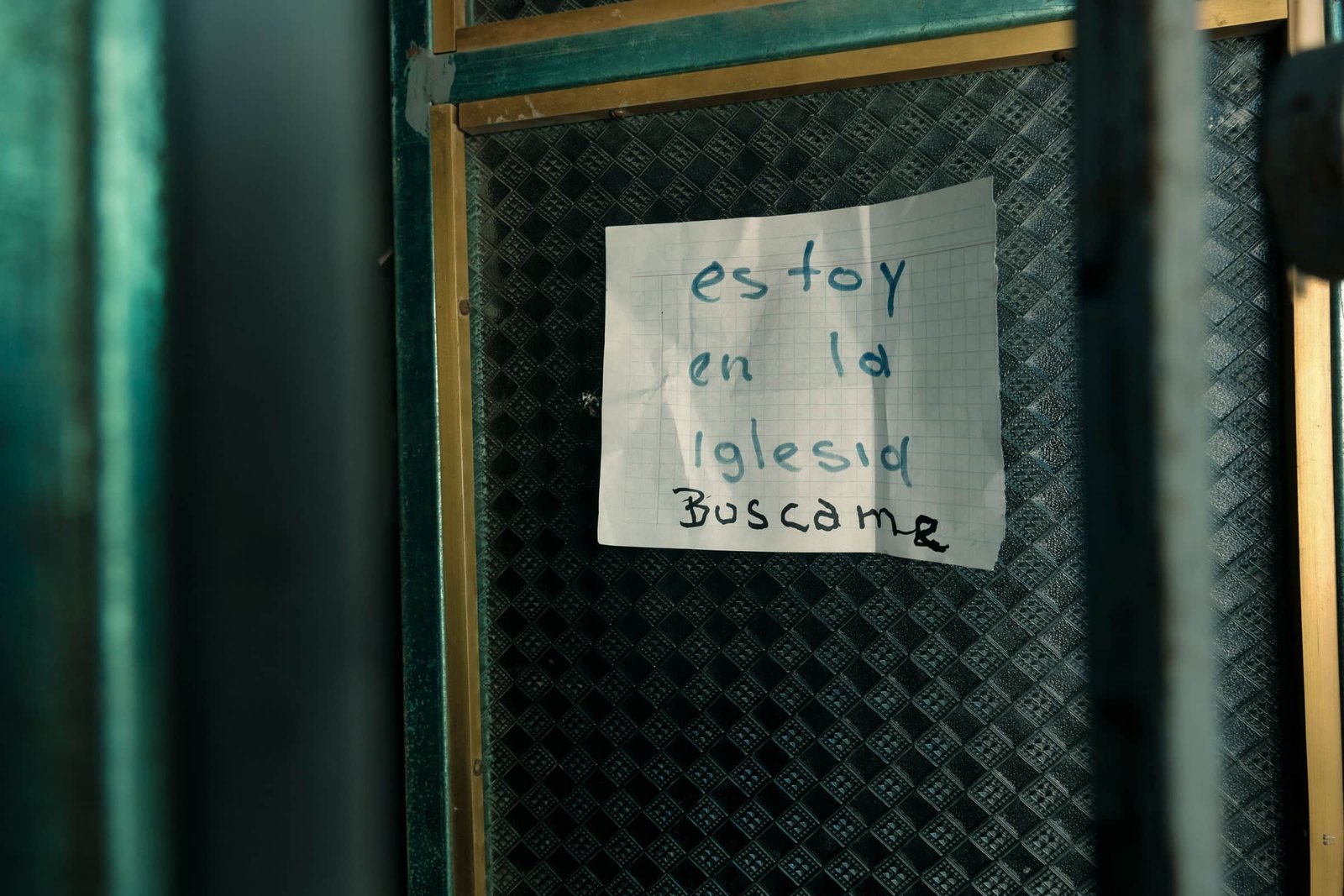

Landis was the Queen of the Muxes at La Vela de las Auténticas Intrépidas Buscadoras del Peligro, the big party that happens every year on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. She shows me one photo after another, proud of how beautiful she looks in her celebration dress. She also remembers that all her savings went to the celebrations; today she can’t stop working. She can’t close her little store because every customer is very important, so whenever she goes out she puts a little sign that says Buscamé (“look for me”) with a description of where she’s gone so that her customers don’t get angry at her absence and stop shopping in her store.

She lives alone with her dog Pelusa. Landis took care of her mother until she passed away two years ago and now, “alone again,” she says, she works, looks after Pelusa, and makes decorations and party favors — she says she has the gift of making beautiful things with her hands because she is very feminine.

Like Landis, many muxes cannot stop their days for interviews and photo sessions, because they need to work. Some charge for their time to be interviewed, which many people do not understand. They charge because it is fair that people who will profit off their stories compensate them. As one of them, Amurabi, told me: the muxes have to work because they have to earn their food.

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is the territory where the muxes can be and exist without fear. That is one side of the story. The other side is the lack of respect and care for them, even though they are frequently the caregivers for aging family members. In more than one conversation I heard, “I’ve resigned myself to being alone.”

What they do have is one another. On a Saturday afternoon you can hardly find anyone at home because they’re meeting for beers or going for walks to talk and laugh with one another while they exist in their muxe universe resisting and creating a new world.

Luvia Lazo is a Zapotec photographer and art lover from Teotitlan del Valle, Oaxaca. Photography is her way of portraying the worlds to which she belongs. Her work aims to capture reality from the perspective of the contemporary Zapotec woman, creating a constellation of images through time and spaces in Oaxaca, documenting the generational gaps and the transformation of identities across ages. She is a recipient of the Jóvenes Creadores grant of the FONCA 2020 (National Fund for the Culture of the Arts, Mexico) and inaugural recipient of the Indigenous photo grant 2021.

previous

You and I, We Are Everything

Kalki Subramaniam

next

my pronouns are super/nova

Taté and Ohíya Walker