No Health, No Care

The Big Fat Loophole in the Hippocratic Oath

Medical fatphobia isn’t the result of providers not knowing some special cheat codes for working with fat patients. Providers didn’t all miss the day in medical school where students were taught how not to be cruel to fat people. Fatphobia is medicine’s status quo.

words by Marquisele Mercedes | art by Rachelle Abellar | 6,187 words | a 26-minute read

The first time I was penetrated I was thirteen, almost fourteen. The lights were on and bright. My gray sweatpants sat discarded on a chair with my stretched-out underwear. My mom was a few feet away, on the other side of a locked door.

Moments before it happened, I was asked in a few coded but unsubtle ways if I had ever had sex. I said no. I was reminded, in case I’d forgotten, that I was a “developed girl” and “developed girls” often got “certain kinds” of attention that encouraged them to do “certain things.” But I had not forgotten; it is impossible to be a young fat Black girl and forget.

I had come to the Pediatric Emergency Department at Montefiore’s Children’s Hospital with intense cramps. I’d been sitting with my mom in a tiny room for nine hours before I was wheeled away to see a doctor. A nurse told her to stand outside and instructed me to undress from the waist down and wait. When my doctor—a thin blonde woman—entered the room, she said hello with a big smile but didn’t tell me her name. She asked whether I was sexually active but didn’t seem satisfied with my answers. Then she told me to lay back, scoot my bottom toward the end of the table, and spread my legs so she could “take a look.” She didn’t explain what that meant or what she was doing or what she had done after it was over. I screamed for her to stop, shouted “No!” over and over. The speculum had painfully snapped inside of me a second time when she said “Wow, you really weren’t lying!” I could only sob with so much helplessness it made my throat rattle. When she finished, she said she would come back to discuss things with me, but she didn’t. I was sent home with instructions to take Motrin and “stay out of trouble.” The STI tests all came back negative.

A pediatric emergency physician looked at me, a thirteen-year-old fat Black girl, and was so certain I was sexually active that she performed a pelvic exam while I screamed and cried and repeatedly revoked consent—if you can claim I ever gave it in the first place. An adult looked at a child and saw a corrupted vessel, a body as full of overindulgence and promiscuity and unrighteousness as it was “obese.”

Does this seem like an unfortunate aberration? Maybe a doctor who’d had a long night in the ER? A bad apple? You are not the first to cling to the comfort of denial.

This is medical fatphobia.

Medical fatphobia refers to the specific ways that hatred and denigration of fatness manifest within medicine and the fields that medicine influences, like public health. It is the reason many fat people likely didn’t get or know to ask to have their COVID-19 vaccine administered with an appropriate-length needle, and why the American Academy of Pediatrics supports bariatric surgery for fat kids despite the incredible risks.

Mainstream writing on fatphobia usually gives in to the myth that there is something exceptional about fatphobic violence in healthcare. That fat people, in all our corpulent clumsiness, are just more likely to stumble across the assholes.

This is not true. It is a lie that has been actively propagated with the assistance of the many not-fat people who have shaped our collective understanding of how fatphobia operates. The truth is that fatphobia is a scientific invention. Fatphobia did not penetrate science; it is derived from science. Everything you know about “obesity,” about fatness, about fatphobia, about fat people has been — and is still — wrong.

A step back: If you want to challenge fatphobia, you have to start with the understanding that fat people are worthy of respect, safety, and dignity. A “but” cannot follow this statement. Fat people are worthy of respect, safety, and dignity. Fat people are worthy of respect, safety, and dignity no matter how fat they are. Fat people are worthy of respect, safety, and dignity no matter how sick they are, no matter how much they eat, no matter how much they move, no matter how far they are from any notion of health, however defined.

Articles that try to correct people’s preconceived notions about ob*sity do not usually start with these assertions. But then again, articles like these are not usually written by fat people and are almost never written by fat Black people. Articles like these are not usually written by anyone with any real skin in the game. But mine is. I’m in the thick of this.

In writing this to you, I am fighting for my life.

In Da’Shaun Harrison’s Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness, the Black fat queer trans abolitionist theorist notes that “for race to be constructed, the Slave had to exist—and had to exist as the antithesis of health—so that European physicians, anthropologists, and other eugenicists could determine what set the Slave apart from the… Caucasian.”

This is the origin story of anti-fatness.

These European thinkers often focused on separating humans into different races by physical features or geographical location and ordering them from best (always White people) to worst (almost always Black people). They used perceived differences in intelligence and attractiveness, customs they witnessed on travels, and the degrading descriptions of African peoples that they read in the work of peers and predecessors. Using this race “science,” these white Europeans linked fatness to blackness by classifying fatness as inherent to non-White peoples. Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus, who developed the binomial system we still use for naming plants and animals, defined four varieties of humans: European white, American reddish, Asian tawny, and African black. Unsurprisingly, White people were declared as the most intelligent race, while Black people were described as “lazy,” “careless,” “covered by grease,” and “ruled by caprice.”

In the mid-1800s, new efforts to measure bodies and populations at the state level produced quantitative data that scientists and mathematicians used to invent normalcy and deviance, including ideal and non-ideal weights. Swimming among these streams of quantification was Belgian astronomer and statistician Adolphe Quetelet, who took statistical theories from astronomy and applied them to decidedly terrestrial data sets: body measurements like head circumference (aka “anthropometric” data) and population data like birth and death rates (aka “social” data). Quetelet found bell curves in both sets, with data clustering around a mean and falling sharply off on either side. At the peak of the curve, the center and highest point, is the average value for the set. For Quetelet, that peak became l’homme moyen: the average, ideal European man. In 1835, he published these findings and more in a series of books that included the Quetelet index: “If we compare two individuals who are fully developed and well-formed with each other, to ascertain the relations existing between the weight and the stature, we shall find that the weight of the developed persons, of different heights, is nearly as the square of the stature.” Ancel Keys, the weight researcher who popularized the Mediterranean Diet and created military K-rations, would go on to define an entire area of research in 1972 when he refashioned Quetelet’s Index into the Body Mass Index to measure ob*sity across different populations. The Body Mass Index was later adopted in 1985 by the National Institutes of Health in the US to define ob*sity. A decade later, the World Health Organization released a report that set the BMI categories and ranges we still use to fat people’s misfortune today.

When you look at a fat person now, regardless of your own weight, you see a manifestation of ob*sity because of a social process called pathologization, which was first conceptualized with respect to fatness by narrative medicine researcher Rachel Fox and her team. Pathologization reduces an individual down to the qualities or stereotypes of a disease as dictated by dominant medical knowledge. When you see a fat person, you associate them with ob*sity. What you believe about ob*sity and have internalized from health authorities—its causes, symptoms, consequences, treatment, and more—then guide your interaction with that fat person. You see an affliction to be cured rather than a human being. Fatphobia starts at the top, with scientific authorities who set the tone for how we think about health and illness, then seeps down to shape the lives of every fat person everywhere.

When fat people are pathologized, they suffer the effects of weight stigma; this is an academic, alienating way of saying they are subject to fatphobic interpersonal, institutional, and structural discrimination. Weight stigma researchers are mostly concerned with how weight stigma relates to individual health behaviors, risks, and events like “poor” eating and exercise habits, mental illness, and mortality because most weight stigma research is in support of “obesity prevention” efforts. Rebecca Puhl and the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health are two of the most notable sources of weight stigma research in public health. Puhl has done Weight Watchers-funded research using WW participants enrolled across 6 different countries. This weight stigma research is specifically intended to help “obesity prevention” efforts function more effectively by giving them a less-stigmatizing veneer. They are far from the only ones. There is plenty of research to paint a gruesome picture of the social, economic, and bodily suffering that stems from fatphobia.

But.

It is proven that weight loss is a useless, hopeless endeavor. You are unlikely to lose weight in any permanent way and highly likely to open yourself to the myriad risks associated with weight cycling. The relationship between weight and health is also muddy. People often mention research that suggests that fatness (up to a point) can be protective, but this often only has the effect of scapegoating the fattest among us, the infinifat people who are only acceptable to acknowledge via mocking entertainment. If you decide (or are pressured to) pursue gastric bypass surgery in order to escape fatphobia violence, you may not actually lose weight — for some, the main outcome is disordered eating, an attempt to salvage the benefits of an incredibly harmful and risky procedure. No study measuring the association between weight and health outcomes comes close to appropriately accounting for the impact of fatphobia on an individual’s wellbeing, including how those impacts are likely the worst for the fattest among us.

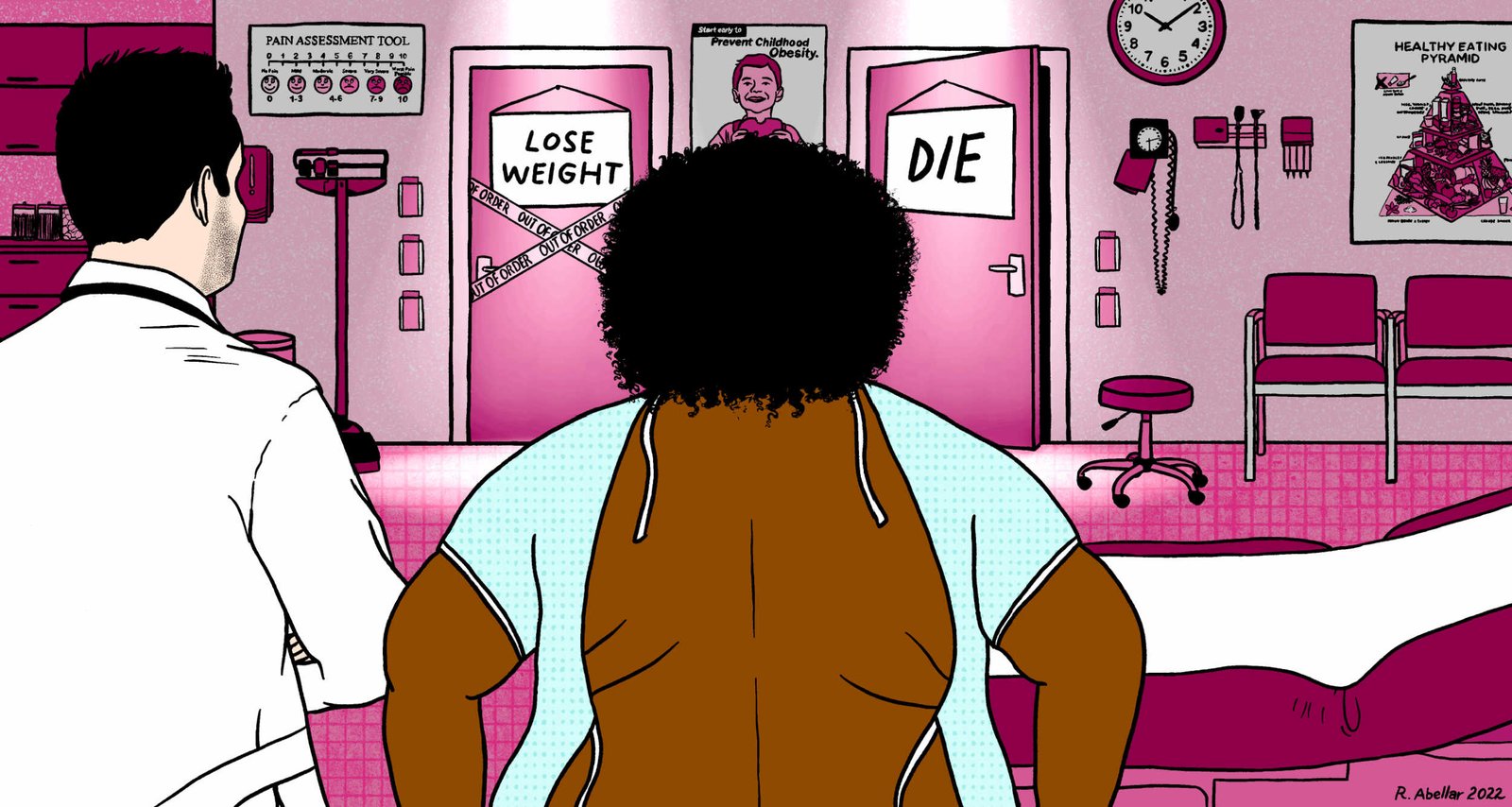

There is no fitness regimen that can keep you moving when doctors refuse to perform a joint surgery you need. There is no diet that can keep you alive when your doctor dismisses the constant pain or discomfort you’re begging them to acknowledge. There are no “health-conscious” behaviors that can nullify the harm done by health authorities who’ve made fat embodiment into disease and weight loss into cure. The only escapes that fat people are offered from a micromanaging, soul-draining existence are weight loss or death. And when we wisen up to the improbability of long-term weight loss, there’s only one option left.

After the incident at Montefiore, I did not go to a gynecologist until I was nineteen. My legs shook from the feeling of being probed with another speculum while I asked the doctor if it was normal to have a chaperone in the room during pelvic exams. She said that it was standard: When a physician learns to perform a pelvic exam, the importance of chaperones, of explaining each step as it happens, of providing gentle encouragement and checking in frequently with the patient is “drilled into you.”

After the exam, I asked her if I could do anything for the heavy cramping and pain that came with each period. I bled through several pads a day and had been getting my period twice a month for the past year. After mentioning Midol, she told me that if I really wanted to have a lighter, more regular period, I should be doing my best to lose weight.

There are many things people don’t quite understand about medical fatphobia. It is more than whether we can pass on getting weighed at the doctor’s office. It is more than healthcare avoidance, although being disrespected, perceived as noncompliant, and exposed to harm by medical professionals are significant obstacles to accessing care. It is more than the potentially lifesaving cancer and breast screenings exams we do not receive and the eating disorder treatment we are deprived of.

Here are the three things people get wrong most often, in no particular order.

One: There is no difference between a) providers who are horrible to fat people because they openly hate us, b) providers who are horrible to fat people because they think it’s the best way to get us to lose weight, and c) providers who are horrible to fat people because they haven’t bothered to learn how not to be. There is no difference to the patient, or the outcome. A healthcare provider’s motivation for harming fat people, often via denying us vital care unless we lose weight, does not justify the harm done or make it any less unethical.

Three. Medical fatphobia isn’t the result of providers not knowing some special cheat codes for working with fat patients. Providers didn’t all miss the day in medical school when students were taught how not to be cruel to fat people. Medical fatphobia is medicine’s status quo.

Robert Rosencrans is an MD/Ph.D. student at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine. “With fatphobia specifically,” he says, “the idea of fatness being intrinsically linked to sickness is so fundamental for most people in medicine that they simply have no idea what you are talking about when you raise a critical point [questioning ob*sity]. It’s like the words lose all semantic content and revert to pure meaningless sound. That’s how profound the disconnect is.” As he wrote in ASBMB Today:

All-cause mortality is as high in underweight people (as defined by body mass index) as it is in patients with higher BMIs … For a thin person, the average scientist and physician believes that cancer, not thinness, is killing that patient. They can locate the source of mortality in something other than body weight or adipose stores. What scientific reason prevents them from extending the same courtesy to larger people?

This is, in part, why most of the weight loss advice you’ve ever received from your doctor is grounded in regurgitated mythologies with no evidence base. Consider the common refrain that “losing just five to ten percent of your body weight has substantial health benefits,” which gets trotted out with thinly veiled exasperation by a doctor that wants you to just try to be less fat or by a weight loss advertisement that is begging to throw you into a yo-yo dieting tailspin. It’s been repeated so many times that it has become accepted as health wisdom, like many things we’re told about weight loss. But a 2013 review of weight-loss diets and their health outcomes exposes the history of this advice:

The original standard weight recommended by physicians was based on the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tables…[T]he tables designated 134 lb as the expected weight for an average-height woman (5′5′′) of medium body frame. Whatever her starting weight, 134lb would be her goal. Obese dieters, however, rarely achieved these standards. Researchers turned to what they considered to be the more realistic goal of 20% weight loss, but only 5% of obese dieters succeeded by that definition. Over the next 30 years, reviews of diet studies showed that individuals tended to lose an average of about 8% of their starting weight on most diets). In an effort to create a more achievable goal, but without any particular medical reason, researchers lowered the standard to just 5% of one’s starting weight.

That’s it. Some people, somewhere, at some point made it easier for diets to be classified as “successful” and that is the reason why we, decades later, have to listen to this little tidbit of nonsense while getting horrible medical care or being accosted by ads for whichever fad diet is interrupting our favorite podcast.

Our lack of knowledge about lipedema—including its etiology, appropriate non-invasive treatments, and methods of early detection—is a consequence of fatphobia. A culture that heavily polices fatness depends on us not knowing very much about fat at all.

It is strange to be in the care of someone you anticipate will hurt you. When I went to a gynecologist at 21 for a copper IUD insertion, I knew the chairs in the waiting room would leave bruises on the sides of my thighs. I knew the examination table would be too small and too high. I knew the nurse who led me to my room would take my vitals with the air of a newbie farmhand handling a sack of manure. I knew I would be forced to stare at her hands as she adjusted the weights on the scale and listen to her say “you know you’re obese, right?” I did not know she would recommend that I try keto, but I guess we’re all surprised sometimes.

I knew my doctor would ask about my sexual activity and wonder just who exactly wanted to fuck that. I knew that my doctor would remind me that, besides the copper IUD, I did not have many other birth control options and that if I wanted to switch to something else, I’d be better off “making lifestyle changes” that helped me “slim down.” I also knew that I would be asked to spread wider than anyone else they’d seen that day, that I’d have to scoot impossibly low on the examination table and balance myself perfectly as my naked ass reddened with the indentation of the table’s edge.

I was not prepared, however, for just how painful it would be to have someone repeatedly try and fail to slide a piece of copper through the opening of my cervix and into my uterus: as if he were pulling the cord at the center of my being with latex-free gloves. I was being unraveled. I cried. After the second try, I told him to stop, that I needed a break. He did not respond or pause and I could feel the pain intensify, a bright line of electricity splitting me in two. I screamed at the top of my lungs that he was hurting me and that I didn’t want to continue. The tension after he yanked out the speculum and stepped away from me… like someone had printed the moment onto a sheet of plastic wrap and was pulling on both ends in as hard as they could.

“If this is going to take multiple tries, you need to fucking stop when I say stop.” I said this as a thin line of mucus fell from my nose and I wiped away the tears in my eyes. I did not feel courageous as I stared at his angular, burning face, nor did I feel vindicated when he apologized.

My doctor tried a dozen times over the course of three hours. At points, I screamed in sync with his attempts to try and relieve something, anything. I was watching the sun set when he gave up, and it was dark when he finally brought in another physician who tried for another hour, but was also unsuccessful.

It took three appointments to get my IUD. The last physician I saw asked me if anyone had mentioned trying a longer speculum or even medicine to help with the pain in advance. They had not.

The medical fatphobia that endangers fat patients also endangers our communities via our public health system. Public health in the U.S. has been largely guided by medical doctors since its inception. Public health students are taught that our work is a population-level complement to healthcare’s individual approach to health promotion. Similarly, public health’s fatphobia works in tandem with medical fatphobia to erode the well-being of fat communities while claiming to advance health equity.

According to the CDC, health equity “is achieved when every person has the opportunity to ‘attain his or her full health potential’ and no one is ‘disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially determined circumstances.’” It stands to reason that fatphobia should be of concern to health equity researchers and advocates; after all, fat people are structurally, socially, and materially deprived of the opportunity to live out our “full health potential” on the basis of fatphobia alone, and many, if not most of us, are multiply marginalized. Unfortunately, the realities of public health mean that most health equity work is not actually conducted with equity in mind. As Dr. Elle Lett and her co-authors argued in a recent commentary on health equity tourism, plenty of (usually White) people without experience in or commitment to promoting health equity have flocked to the health equity space because they see the potential for research productivity or fiscal return. Many also try to shoehorn their existing work into the health equity framework: “Oftentimes, these scholars seek to ‘retrofit,’ or adapt existing structures and research practices for health equity work, rather than build the necessary transformative infrastructure required for sustainable health justice.”

The Treat and Reduce Obesity Act, which was first introduced in 2013 and has always had bipartisan support, claims to promote health equity using the backward approach Kriete describes. One proposed element of the Act would broaden Medicare coverage for intensive behavioral therapy to reimburse more providers, as well as cover FDA-approved weight loss medications under Medicare Part D. A supportive op-ed by Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford and Kelly Copes-Anderson points out that “nearly 50% of Black adults and 45% of Hispanic adults have obesity,” before arguing that “the significance of these two advancements goes beyond treating individuals with obesity. They represent a decisive moment in shifting society away from viewing obesity as caused by individuals making poor choices and toward treating obesity as a manageable chronic disease like asthma or high blood pressure. This is a crucial step in eliminating bias against people with obesity, which has hobbled efforts to address this epidemic even as it fuels health inequity.”

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Open Payments website, which has data on payments made by drug and medical device companies to physicians and teaching hospitals between 2016 and 2020, Stanford received over $17,000 from pharmaceutical giants like Novo Nordisk. By her own admission, she does up to 200 interviews with news media and an average of 150 lectures per year about “obesity as a disease.” Her co-author, Copes-Anderson, is employed by Eli Lilly as their head of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Eli Lilly is currently awaiting FDA approval of its anticipated ob*sity medication tirzepatide and hopes to follow in the footsteps of competitor Novo Nordisk, which is making billions from sales of its ob*sity drug, Wegovy, released in 2021. If the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act is successful and Medicare Part D coverage includes drugs like tirzepatide and Wegovy, pharmaceutical companies will make a killing, as will “obesity medicine” practitioners .

This is the fatphobia industrial complex: the cluster of entities using fatphobia to sell products and services that provide the influence and capital needed to exert control over large swaths of people and regulatory bodies for the purposes of making profit, repeated ad nauseum. Their appropriation of health equity language is a tool to further the idea that ob*sity is a disease requiring prescribed cures, making pharmaceutical companies and ob*sity specialists into fat people’s saviors. And their ability to do these things while referencing research that demonstrates the uncontrollability of weight—research that well-meaning people use to criticize fatphobia—is further proof that fighting for fat people’s rights on the basis of how healthy they are will never make us free.

The articles that inspired this one—the most popular mainstream interrogations of ob*sity and its associated stigmas—often contain proposed solutions that just feed back into the pathologization of fat people. Providing financial incentives or reimbursement for ob*sity-related treatment or counseling will not dismantle fatphobia; all this does is funnel fat people into hostile situations with even more health care professionals who can get reimbursed for providing inaccurate, harmful, and presumptuous advice. Educating healthcare providers on the genetic causes of ob*sity will not dismantle fatphobia; we have more than enough evidence that demonstrates this approach is useless at best and can actually worsen anti-fat attitudes. Moralizing food by claiming that the real problem is the proliferation of “junk” food and lack of access to healthier will not dismantle fatphobia; labeling foods as good or bad relies on anti-fatness and is often a coded way of demonizing foods from non-white cultures, inexpensive foods, or foods that fit into the lifestyles of workers.

The solution to fatphobia will not emerge from more medicine or sensitivity training or cheaper organic groceries. If you want to disrupt fatphobia, you must, as Harrison wrote in Belly of the Beast, “destroy the World that produces the cage by which the Black fat is bound.” This is to say that for the purposes of dismantling fatphobia, it is not enough for us to join in the abolition of institutions that kill us; we must join together to snuff the World, the place fertilized by anti-Blackness in which those deadly systems and institutions first came to fruition. We must commit to tearing down what does not serve the most marginalized of us until the day comes when there is nothing left but possibility. Once we get there, we’ll figure out together what happens next. Harrison writes, “[W]hat happens beyond can’t be answered until the Beyond is here. What we do know is that this—the World—can no longer exist.” On days when I feel particularly hopeless, I keep that last bit in mind. You do not have to know what the next world looks like to know that the one you live in right now must no longer exist.

In my mind, the path to that destruction is an endless trail of decisions. We must decide, over and over again, to kill what kills fat people. Things that may come to mind first are actions like joining a campaign for laws against weight discrimination. But I believe in you now, so I’m challenging you to go beyond the false security of anti-discrimination legislation and think about community care.

Think of someone you love deeply. Would you help if they couldn’t pay rent or afford groceries? Would you check in on them if you hadn’t heard from them in a while? Would you give them a ride to an appointment? Would you help them clean up if they were overwhelmed by a mess? Would you listen to them if they needed to share? Would you watch their kids if they needed emergency childcare? Would you comfort them if they needed to cry? Would you sit and help them budget? Would you show support if they lost someone they loved deeply? Would you promote their work if they made something they were proud of? Would you go with them to the doctor if they needed an advocate? Would you help bail them out of jail? Would you mend their clothes? Would you defend them if someone was hurtful to them in front of you? What would it look like for you to do things like this for others who you may love less, but who deserve to be supported regardless?

Caring for each other is how we survive to do the rest of our work. This is not meant to downplay the serious abolitionist work that needs to be done in order to create marked change for fat people, but there is no change without care. We cannot demand divestment from the BMI without care. We cannot raise our kids to reject body hierarchies without care. We cannot raise our kids to know their fat bodies are worthy without care. We cannot terrorize weight loss companies or be a menace to their corporate advocates without care. We cannot keep young fat Black girls safe from medical trauma without care. We cannot challenge profit-driven disinformation about weight without care. We cannot hold doctors accountable for the ways they hurt young fat Black girls without care. We cannot cultivate spaces for learning and political education outside of exclusionary universities without care.

Articles like these—the ones that try to correct people’s preconceived notions about ob*sity or weight—usually do not end with fat odes to care. But like I said: articles like these are not usually written by fat people and are almost never written by fat Black people. Articles like these are not usually written by anyone with any real skin in the game. But mine is. I’m in the thick of this. So are a lot of people I love.

In writing this to you, I am fighting for our lives.

Marquisele Mercedes is a writer, creator, and doctoral student from the Bronx, New York. As a Presidential Fellow at the Brown University School of Public Health, she works at the intersection of critical public health studies, fat studies, and scholarship on race/ism, examining how racism, anti-Blackness, and fatphobia have shaped health care, research, and public health. She is passionate about using public scholarship to make science and research accessible outside of academic institutions, as well as reshape health scholarship and interventions to make the world safer for fat people of color

Rachelle Abellar is a Filipino-American designer, community organizer, and body liberation activist whose work is informed by her various intersecting identities as well as her commitment to inclusivity, diversity, and community. When she’s not busy making things look shiny, she enjoys going to art museums and cat cafes, listening to k-pop, and running an online stationery shop with her best friend.

Editing and layout, Michelle Weber

Copyediting, Soraya Roberts

Fact checking, Matt Giles

next

Field Notes From a Fatty

Athia Choudhury