Ana Hurtado

no. 8, The Road Trip Issue

Autumn 2022

I. Of Dirt

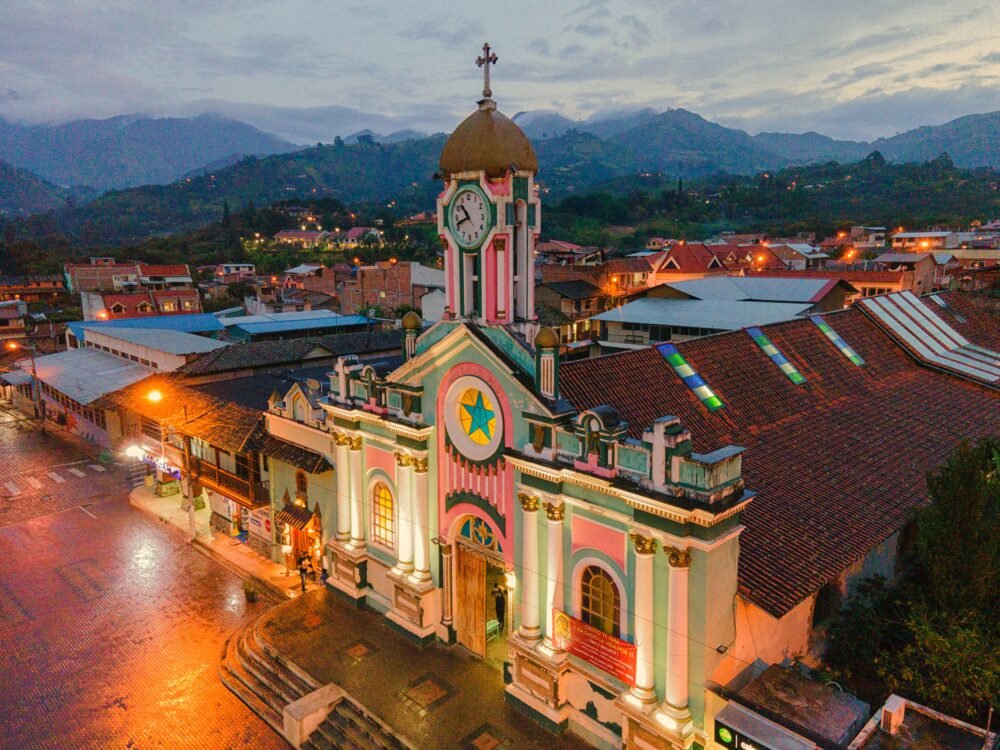

I drag my mother’s shovel across cobblestones, the one I took without her permission. Baños de Agua Santa’s marching band dodges me and the trumpeter plays a note that stings my ears. Around the corner is our local cemetery, where my brother is buried. At noon, while the town follows the festivities, as their eyes are set on our porcelain virgen who sits on a velvet pillow draped across the shoulders of my classmates, I don’t join the carnaval. Today, amongst trumpets and chants, I will unearth Sebas.

It takes me a while. Clods of dirt land over my shoulders, some soil hiding inside my shirt and underneath my nails. Worms have disintegrated the coffin and my brother’s skin, too. I place the red petals I had shoved into my pocket up my nostrils and take in a deep breath. When I see my brother’s blackened skin beneath the suit he never wanted to wear, my hands begin to shake. Tears wet my cheeks and land on his coffin’s pillow. I stand here, above him, and remind myself that I’m trying to save him.

With the back of my hand tainted by our town’s dirt, I tap my brother’s cheek. It is soft and cold. Nothing happens. I tap again, this time looking over my shoulder to see if anyone has followed me, if my mother has noticed I’m missing. Only a couple of brown birds hang on the telephone lines above me. When I look back down, I see my brother looking up at me. Yellowed eyes, straight teeth, all there, smiling. It’s him. It’s Sebas, my big brother, el rebelde.

Ñaño, I say to him. Vamos, we’re gonna be late! I stand up, brush the earth from my body, and help Sebas get up. He doesn’t speak, but his eyes tell me he knows it’s me.

Together, we climb from his grave and join the procession, his cold hand on mine. His feet stumble on the cobblestones; it’s as if he has outgrown his shoes. Sebas leans on me sometimes, but when he realizes where I have taken him, where he has come from, he stops walking. Townsfolk pass us by, nobody noticing the dead Sebas standing under our equatorial sun.

Vamos, I insist, pulling at his suit’s sleeve.

He shakes his head.

We stand in front of our church, where most of Baños has crammed itself into the tiny chapel to pray for the dead.

Somebody at school told me because you aren’t baptized, you’re not worthy, I confess to him, and his yellowed eyes look into mine. This is why I brought you here today, I add.

He offers me his hand of bones and worms and again shakes his head No.

The icicle tricycle’s bells ring around the corner, and Sebas winks at me. I smile back.

While the entire pueblo prays inside our only church, I sit on the sidewalk and eat a coconut popsicle with my ñaño.

II. Mete gol, gana.

Lightning was first. It struck the wet wood and electrified it. The wooden cross burned on top of our colossal mound, the one that looks like a sharp nose, and illuminated our páramo at night: flames, the lichened mud that likes to swallow us whole and then burp us out, baptizing us in brown; scorch, the black bunnies and orange foxes who scattered and made their way to me, huddling behind my feet; crackling, the sound of a whip, the yellow blossoming flowers who turned their petals away from the fire. The cross burned all night.

In the morning, Papá told me the cursed cross must be taken down, its remains excavated and plucked from the earth.

What will they do with it? With la cruz? I asked him.

I think they wanted to bury it, papá said as he sipped his morning coffee and rewatched the tape of the Ecuador versus Brazil game. But when los hombres approached it, their hands only grasped ash. It disintegrated in their palms, he almost whispered.

Well, whatever, I respond.

They’re gonna build a bigger one now, he continued, almost a warning.

Today, in our fútbol field where the white boundary lines aren’t chalk but tiny mushrooms dressed in bone white that my friends and I placed and arranged — the fungus love to see us play soccer —I watch the men take apart our only metallic goalpost. They slash the metal tubes with a chainsaw.

Ey, ey, ey! I say as I run up to my best friend Mateo. He crosses his arms in disbelief.

They’re taking it from us, he says to me, and a páramo wind from the inner throat of volcán Cotopaxi carries his words far away from me, into the depth of crevasses, earth opened and cracked from volcanic explosions — and beyond, where our cóndores glide amongst snow.

Wouldn’t a metallic cross also just attract more lightning? I ask Mateo, theorizing.

They don’t care. They don’t care at all, he replies, his arms now down to his sides, his fingers closing into a fist.

Tonight, Mateo and I walk up to the hill where the sky once decided it should burn. We touch the tall metallic cross with our fingertips, the cold staining the bar in the shape of us, our grooves of lava. I take off my backpack and retrieve the fútbol net we stole from our own soccer field. Mateo and I pretend we’re fishermen and toss the net over the cross, and it stands like a giant spiderweb, waiting for its prey. Mateo smiles at me.

In the morning, it isn’t Papá who wakes me up. It’s Mateo, whose cheeks are so red from running all the way from his house to mine. He grabs my arm and pulls me to my window. With his sleeve he cleans away the fog, and I spot the metallic cross on top of our highest hill, draped in a white web, and within its lacing, all tangled, is an obsidian condor, trapped.

III. Difunta

I hear I was found amongst trees. The pine trees whose cones surrounded me and my body, outlining my shape. I think it was when one kid kicked the fútbol ball aiming at the goal and missed, and the pelota rolled and rolled, dodging bikes and dogs and old men with canes, and somehow landed near my fingertips, the leather strap of my purse ensnarled around my wrist. Or maybe it was the teenagers who had snuck away from school and ran into the park’s osbcurito to hide from it all. Maybe it was they who tripped over my feet, my naked and muddy toes facing up towards a rainy sky, a band-aid on my heel to help me with the strappy sandals that liked to pierce my skin. Yes. I think it was the teenage love birds who discovered me.

I like to think that on those first few days of November, when the city of Quito drinks its weight in colada morada for día de los difuntos, my mother makes a bread in the shape of me. I know she remembers me. I can hear her in the kitchen, flour dusting her nails and knuckles, reminding me yet again how to roll up the guagua de pan, the mummified bread meant to represent the dead, me: Use the rolling pin that’s in the fourth drawer. Pull it out and spread out your dough. Come on, use your muscles. Once it’s smoothed and thin, drop in your filling with the spoons I placed to your right. Yes – another chocolate and hazelnut one is fine. Now pinch in its body, drape it over its filing, its insides. Cut out its arms, pull them out to its sides and then cross them over its body. Ahí. A body in a coffin. Don’t worry about its face. We will draw one when it’s cooked and hot and out of the oven. And when we do, don’t tear the baby’s body with one bite.

Ana Hurtado is a speculative fiction writer. Born in Venezuela and raised in Ecuador, she explores these post-colonial environments through magical realism. She earned an MFA in Creative Writing & Environment from Iowa State University in 2017 and now teaches creative writing at Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Her work has been published by The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Strange Horizons, and Fireside Magazine, amongst others.

More great reading

from Pipe Wrench no. 8

Two Poems

The insistent cadence of Samuel Cheney’s poetry pulls you along as surely as Parley P. Pratt was pulled down the Weber River in 1850.

Van Life

When you’re on a road trip, searching for Truth, you need tunes. Michael Ventuolo-Mantovani has your playlist.

Never Say Never

Scholar Brittany Romanello tries to answer the question: Am I still Mormon? A personal essay on embracing faith and ambiguity.