And if all the things which I saw are not written,

the things which I have written are true.

– 1 Nephi 14:2

On the thirteenth day of our journey, we beheld that hill of which our leader had foretold. For half a day we had journeyed on winding roads rutted with stones, betwixt high mountains lush with tropical verdure. We were, to the one, thousands of miles from those lands where we have made our homes, and we were tired, and eager for fare beyond that which one finds at stations proffering only peanuts and gasoline. And it was then, with great relief apparent upon his rugous visage, that Blake, son of Joseph, descried Xim — that Hill Shim! — and proclaimed with great fervor that this was the place. And he commanded unto Jesús that we make our stop, whereupon Blake, son of Joseph, pointed at a hill, unremarkable in aspect, there distant upon the horizon.

And it came to pass that Blake, son of Joseph, spake unto the driver Jesús, whose bewilderment was readily discerned. Somos mormones, he explained. We believe that, thousands of years ago, important historical records about ancient civilizations were buried in a hill called Shim — and eventually, an angel revealed those records to the prophet Joseph Smith. Delight was evident upon Blake’s rugged countenance. And that’s why I asked you to stop. Because all of us wanted to be able to take a good long look at that hill.

And it came to pass that Jesús nodded and did remark with great tepidity: “Muy interesante.”

Of course, I also could have written that as a headline:

Avowed Atheist Joins Mormon Tour in Mesoamerica in Name of Journalism

Or in the style of modern-day truthteller Ira Glass.

Under the Banner of Heaven. The Book of Mormon musical. Mitt Romney. Mormonism has gotten a lot of attention recently. You might be even saying to yourself, “Hey, isn’t that the religion that says a teenage boy found some golden plates in upstate New York that told him that Jesus preached to Indigenous civilizations in the Americas?” And you’d be right.

But here’s something you might not know about Mormonism. There are groups of believers with lots of theories about where their distinctive scripture takes place. Some believe it took place in the American midwest, others in Baja California. But the most popular theory is that the events took place in northern Guatemala and southern Mexico, where ancient Mayan and Olmec civilizations lived, in the region archeologists call Mesoamerica.

And investigating those claims opens up a lot of questions. Questions about cultural appropriation. About the limits of history, and of science. About the very nature of truth.

None of these are any more correct than any other. They might speak to you differently, depending on who you are and what language has been most formative to your soul. We filter the world through the muscle of our experiences, our perspectives and our biases, everything we’ve ever read and thought and lived. This is just as true for journalists, who are always wrong in claiming that there is such a thing as objectivity, as it is of historians, of archeologists, of scholars of religion. And, though the travelers on the summer 2022 Nephi to Cumorah Deluxe Tour would probably disagree, I’d argue that it’s also true, perhaps especially so, of prophets.

Which is all to say: There’s always more than one way to tell a story.

But let’s go with: this is a True Record of that time that Emily Kaplan, a 36-year-old atheist Jew from Brooklyn, accompanied a bunch of Mormon grandparents on a Mexican road trip for teetotaling AARP members with colonizer mindsets. Any one of my travel companions would tell this story differently; apt, since the project of Book of Mormon Tours, a one-man company headquartered in Richfield, Utah, is one of retelling. It is based on the premise that the widely-accepted histories of swathes of Mesoamerica, from Guatemala’s Lake Atitlán in the south up to the Mexican coastal city of Veracruz — histories compiled through archaeological research and these communities’ own written and oral documentation — are wrong. Or at least incomplete: they all fail to mention that all of the Indigenous peoples of the region were descended from ancient Near Easterners who’d sailed to the Americas from the Middle East in the 7th century BCE, that Jesus arrived a few hundred years later, that the names they went by were incorrect, and that the most righteous among them abandoned their ways and adopted Christianity upon hearing Jesus’s preaching. In other words, the premise of Book of Mormon tours, and all the other tours like it, is not only that Indigenous Mexicans and Guatemalans are ignorant of their own history, but that their history provides incontrovertible evidence that Mormonism provides the only right way to think, to believe, to live.

Here’s how it goes in the Book of Mormon. By around 591 BCE, a group called Nephites sailed from Jerusalem to somewhere in the Americas, establishing the city of Zarahemla. It doesn’t say exactly where, but the book includes lots and lots of place names — the Waters of Mormon, the Land Bountiful, the Land of Lehi, Mulek, Gomorrah, the River Sidon — along with pretty specific geographic orientations. Take Bountiful: it must be very fertile, with “much fruit and also wild honey,” and have cliffs overlooking the ocean, because Nephi’s brother tried to throw him “into the depths of the sea.” It must be located, therefore, on a coastal forest (which the Nephites used to build their ships) and have sources of ore and flint (required by those ships). This specificity comes in handy if, as a Mormon who’s invested in the historicity of your religion’s titular text, you’re trying to figure out where all of this took place.

And if you’re Blake, you’ve narrowed it down to Guatemala and southern Mexico, and you have a binder full of evidence to make the case — not only for the geographical parallels but historical ones, too. Because the Book of Mormon isn’t just about all the places that Jesus went: it’s about the very long list of events that transpired before and after his visit. First, the City of Nephi was conquered by the Lamanites, a people whose skin had turned dark after rejecting Jesus’s teachings. Then the Nephites fled to Zarahemla, which Blake says he has good reason to believe is located in the Chiapas depression, near the city of Tuxtla Gutiérrez in the southernmost region of Mexico.

You might be wondering how these ancient Jews developed boats that could cross oceans, given that this maritime technology wouldn’t be commonplace for another few thousand years, but there’s a lot in Latter-day Saint theology that doesn’t square with secular history and science. Instead, to understand the Book of Mormon as a historical document, they’ve embraced a mindset that professors of English might call suspension of disbelief but which traditional Mormons call faith. Faith that God enabled these miraculous acts in order to bring about Christ’s one true church on earth. Faith that there are limits to human comprehension, science, and history, but no limits to divine power. Faith that the people telling you these things have your best interest at heart, want you to be able to enter the celestial kingdom after you die. Faith that your belief system is good both for you and for the world.

from “The Fight Over Book of Mormon Geography”

by Michael De Groote, Deseret News

May 27, 2010

…Something is rotten in Zarahemla — wherever it may be.

In the middle of what could be a fun and intellectually exciting pursuit similar to archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann’s famous search for the lost city of Troy, there are accusations of disloyalty tantamount to apostasy.

In one corner is the more-established idea of a Mesoamerican setting for the Book of Mormon. This theory places the events of the book in a limited geographic setting that is about the same size as ancient Israel. The location is in southern Mexico and Guatemala. The person most often associated with this theory is John L. Sorenson, a retired professor of anthropology at BYU, and the author of “An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon” and a series of articles on Book of Mormon geography that ran in the Ensign magazine in September and October 1984. A new book, tentatively titled “Mormon’s Codex,” is in the process of being published.

In the other corner is the challenger, a new theory that places Book of Mormon events in a North American “heartland” setting. Like the Mesoamerican theory, it also is limited in area — but not quite as limited. Its symbolic head is Rod L. Meldrum and, more recently, Bruce H. Porter. Meldrum and Porter are the co-authors of the book “Prophecies and Promises,” which promotes the heartland setting.

It wouldn’t be hard to predict that some friction might come about from competing theories — that healthy sparring would occur with arguments and counter-arguments. But it has gone beyond that…

I joined the group after they’d already been traveling together for about a week in Guatemala. It came to pass that Blake met me in the morning while the others showered and changed after church. Blake has a fresh khaki shirt and Book of Mormon citation for every occasion imaginable and has been leading tours since his father Joseph founded Book of Mormon Tours in 1970. He opened his worn Book of Mormon and said that, before anything else, I needed to understand something crucial: that the Book of Mormon contains a kind of palindromic structuring called chiasmus — what poets might call ABCBA — that is incontrovertible proof of its Semitic origins, and therefore its divinity.

And the Jews shall have the words of the Nephites and the Nephites shall have the words of the Jews. And the Nephites and the Jews shall have the words of the lost tribes of Israel and the lost tribes of Israel shall have the words of the Nephites and the Jews. (2 Nephi 29)

I wanted to ask him more, literature-lover to literature-lover, but by then the rest of the tourers had arrived, at various stages of wakefulness.

Note: the names of tour guests have been changed to protect their privacy.

Along with Blake and me there were Matt and Amy, spry, exuberant grandparents from small-town Utah. And then there were the great-grandparents from back-country Oregon: plump, sarcastic Betty or Delia (“Call me either, but not both”) and her husband, who calls himself Old Man Earl, had last been to Mexico as a missionary in the early 1960s, and seemed a bit affronted that the country had changed somewhat since then. Even in the stifling heat, Old Man Earl wore pressed button-up shirts and his hair in a neat comb-over; back at home, he told us, he had twelve pet deer and reveled in his third-act identity as a gentleman farmer.

I’d just gotten back to the table with a tray of tortillas and beans and found Old Man Earl mid-tale. “And would you believe it? My gramps, he says to me, he says, ‘Little Boy Earl, go down there yonder and shoot that bear dead.’ And I says to him, I says, ‘But all I’ve got is my shotgun!’” His voice was growing louder. “And would you believe it? I went down to that river. And I climbed that tree, I did. I shimmied up that trunk, I did! And then I reached that bear. And it wasn’t a small one, neither!” Sweat was beading on his brow.

Amy leaned over and whispered in my ear: “Earl really likes to tell stories.” She snuck a quick glance at me, smiled, resumed slicing her bacon.

“And I took one look at that big fella, and then—BAM!—I whacked that fella right in the you-know-what! I sure did! Didn’t even need that pistol after all. And he—”

Blake looked up from his plate. “Now hold on a minute there, Earl. How old were you when all this happened?” Amy seemed to stifle a giggle. I decided right then that I liked this woman.

Old Man Earl looked taken off guard. “Well, I was, you know, already a married man at that point. A father. So.” He paused, thought for a moment. “Well, I’d say I musta been twenty-three, twenty-four years of age.”

I swallowed a mouthful of beans, then spoke. “When you said you were a little boy, I was picturing you being, like… eight.”

Betty patted her husband on the shoulder as the whole table looked pointedly at me. “Well, if he was only eight, he couldn’t have killed that bear with his own two hands, now could he?” She raised her eyebrows and slowly shook her head.

I swallowed.

And it came to pass that later that day, we were walking between Tuxtla Gutierrez’s Anthropology Museum and the city’s zoo, discussing the theory that the prophet Nephi had played a significant role in creating the Mayan calendar. At the museum, Blake explained that archeologists had determined that a civilization from the south had been conquered by a dominant civilization on December 6, 36 BCE — which lined up nearly exactly with the known chronology of the Lamanites’ conquest of the Nephites. That, coupled with the overwhelming geographic parallels between the city of Sidom and this region of Chiapas — was, well. It was certainly very interesting indeed.

Matt and Blake walked briskly, discussing the theory’s nitty-gritty details, Matt peppering Blake with very specific follow-up questions. Amy and Betty/Delia ambled silently beside them.

Old Man Earl sidled up to me. “You know,” he said suddenly, “I just love literature. Some of those writers just, you know, there’s nothing like ‘em. Nathaniel Hawthorne. Henry David Thoreau.” He paused, thought for a moment. “And of course Robert Louis Stevenson. Just amazing.” He looked at me and smiled kindly.

It took me a second, but I realized what was happening. In the van, Blake had mentioned that I’m a journalist; Old Man Earl was searching for a point of connection. I looked at him — his delicate glasses frames, the branching rivers of laugh lines around his deep-set eyes — and saw that he looked a bit like my grandfather.

“And who can forget Mark Twain?” he continued. He was on a roll now. “Tom Sawyer? That story about that jumping frog? The man was a genius.”

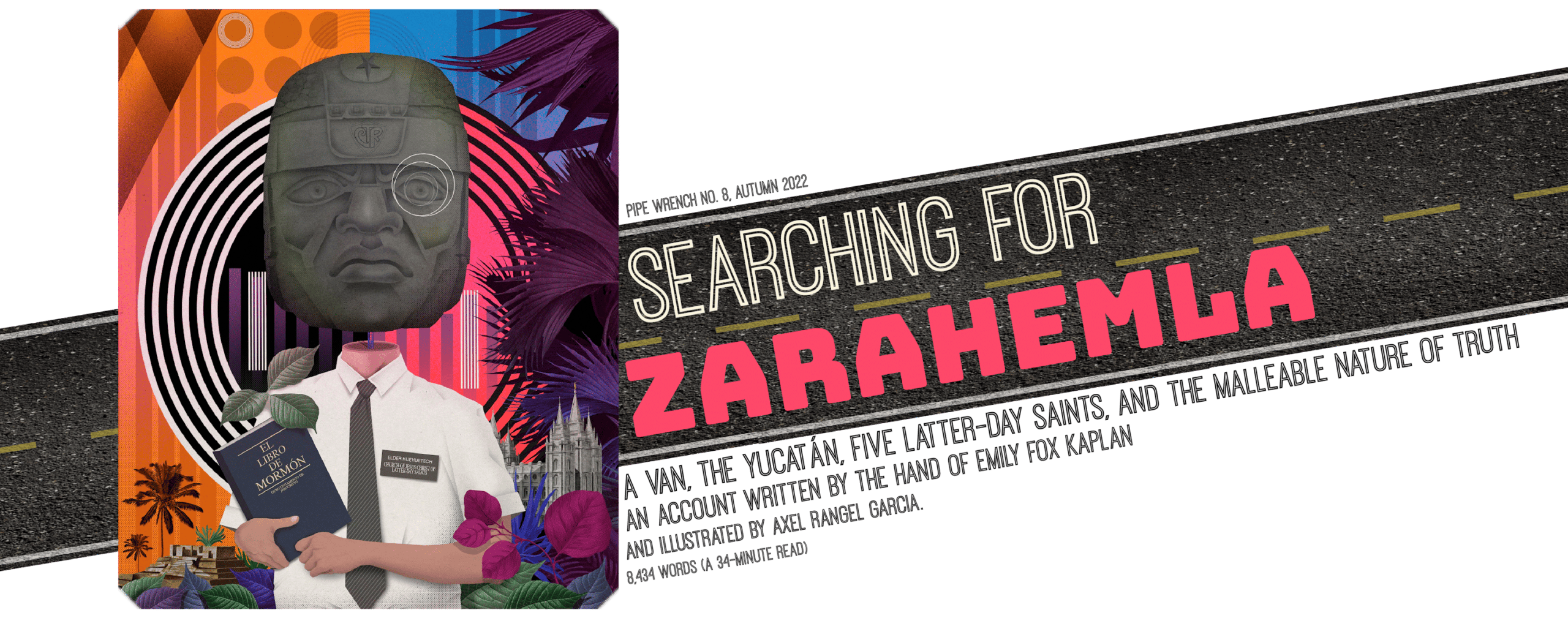

about the symbolism Mexico City-based illustrator

Axel Rangel García wove into his artwork.

I nodded. “I love Mark Twain.”

He smiled. “You know,” he said, a glint in his eye, “Mark Twain had a lot to say about the Book of Mormon.”

My reporter brain switched on. I looked at him, feigning ignorance. “Oh?”

“Oh yes,” he said triumphantly. “It was Mark Twain who said, you know, that without the phrase ‘And it came to pass,’ that the Book of Mormon would only be ten percent as long.”

I smiled. “Did he really? I like that. That’s funny. And true.” But I wasn’t sure he heard me; he was shaking his head, chuckling to himself.

That evening, we found ourselves around a large round table, studying the hotel menu. Everyone was discussing some senior missionaries who’d served with Betty and Old Man Earl at the Polynesian Cultural Center, a Mormon institution whose ostensible purpose is to celebrate Polynesian culture in Hawaii, but which makes tens of millions of (untaxed) dollars for the Church and is run by old white people. Betty had been its seamstress, sewing “those beautiful costumes all the little Hawaiian ladies wear,” and the colors she’d been seeing on this trip, she told us, reminded her of Hawaii. Then talk moved on to this other guy, this nice guy who ran that hardware chain in Salt Lake. He’d gone to Brigham Young with one of them, served as a bishop in such-and-such a place. His wife’s cousin’s daughter had been a sister missionary with so-and-so’s daughter. In Africa, they thought. Or, no. That country next to Argentina. Honduras.

I piped up: In my culture, I said, we call that do-you-know connections game “Jewish Geography.”

They all turned to me, blinking. Then, after a long moment, Old Man Earl patted me on the arm. “But we’re not Jewish, dear.”

In the silence that followed, I picked up the little silver bowl of green hot sauce, poured it over my rice and refried beans. Then Blake looked directly at me. “So,” he said. “Why don’t you tell us how it was you first got interested in our Church.”

I took a deep breath. And I told them about how I’d majored in anthropology, done a study of the Latter-day Saints Student Association at my school for a sophomore paper, and been following developments in their culture ever since. I told them that when Covid prohibited me from traveling to cover immigration, my main beat, my editor and I brainstormed other topics and I suggested I could write about the future of the Mormon Church, which seemed internally divided after the 2016 election. I didn’t tell them this, but I’m telling you, here, now: I think I find Mormons so compelling because Jews don’t have any certainty about anything. Have you heard the saying, “Two Jews, three opinions?” Mormonism is the opposite; 16 million-plus Mormons, one set of very specific answers to pretty much every question imaginable. Follow these explicit guidelines to progress to the highest tier of heaven.

“Well that’s very interesting,” Amy said, and the rest of them nodded, somewhat skeptically. “What was the name of your article?”

“It was called ‘The Rise of the Liberal Latter-day Saints.’”

Matt cocked an eyebrow, and Amy looked down at her plate. Betty looked at her husband and shook her head disappointedly. Blake asked what my article was about, exactly. And I explained: it focused on groups of people who have long felt rejected within the church — gay people, feminists, Democrats — and the ways they’re gaining a hold in the institution and the culture. (What I didn’t say: many of these liberal Mormons — who tend to view the historical claims of the Book of Mormon with skepticism, to say the least — are a bit horrified by tours like Blake’s.)

I paused, choosing my next words carefully. “I’m very aware that your Church has often been misportrayed, has been mocked by the mainstream media. And that’s not okay. I take the responsibility to cover your Church very seriously. I’m an outsider, and I know that.”

I picked up a taco, tilted the bottom towards my mouth, brought it slowly to my lips. Green sauce dribbled down my wrist.

Betty looked squarely at me. “Emily,” she said, “Have you ever read the Book of Mormon?” I told her I had.

“And have you had the missionary lessons?”

Journalists have to walk a fine line with sources: be truthful, but also vague enough to build trust, to get information. But I do not believe in half-truths. In my reporting with migrants from Central America, I get asked a lot about whether I believe in Jesus. Sometimes it’s phrased differently: Es Ud. creyente? Are you a believer? It’s another way of asking: Are you one of us?

“No,” I told her. “But I’d be very interested in having them. Just like I’d really be so curious to know about temple rites.” I paused. “But I don’t want to mislead anyone, give the impression that I’m personally interested in converting. Because I’m not.”

Betty cocked an eyebrow. “Well, never say never.”

Later that night, I was lying in bed in my hotel room, trying not to think about the dissolution of one of my dearest friendships. I googled: “mark twain + book of mormon.” Old Man Earl’s phrasing had been off, but he’d gotten the gist right. In the early 1860s, Mark Twain — then still a would-be silver miner named Samuel Clemens — embarked on a series of adventures in the American West. In 1872, he published his accounts in the not-very-veiled autobiographical novel Roughing It. In it, he devotes a handful of chapters to the Mormons, a rabble-rousing band of polygamists getting chased from state to state as their leaders did things like run for president, try to found a socialist nation-state, and publish articles claiming that Christopher Columbus, Moses, and all of the Founding Fathers had appeared in prophetic visions to express their admiration. And in Chapter 16 (titled, in that great 19th-century compound way, “The Mormon Bible—Proofs of its Divinity—Plagiarism of its Authors—Story of Nephi—Wonderful Battle—Kilkenny Cats Outdone”) Twain gives his take on the group’s essential text.

The book seems to be merely a prosy detail of imaginary history, with the Old Testament for a model; followed by a tedious plagiarism of the New Testament. The author labored to give his words and phrases the quaint, old-fashioned sound and structure of our King James’s translation of the Scriptures; and the result is a mongrel—half modern glibness, and half ancient simplicity and gravity. The latter is awkward and constrained; the former natural, but grotesque by the contrast. Whenever he found his speech growing too modern—which was about every sentence or two—he ladled in a few such Scriptural phrases as “exceeding sore,” “and it came to pass,” etc., and made things satisfactory again. “And it came to pass” was his pet. If he had left that out, his Bible would have been only a pamphlet.

I fell into a fitful sleep.

On the Road with the Tourers Five

Click a marker to follow the route of Kaplan’s tour through Central America, and learn why Book of Mormon geographers — including Kaplan’s guide — consider each location to be historically and theologically significant.

Guatemala City, Guatemala

The tour kicks off in Guatemala City, Guatemala’s capital and largest city. Humans first settled in the area around 1500 BCE, when the Maya built the city of Kaminaljuyu. It eventually collapsed, in 300 CE. Later, conquistadors built a town around a kilometer from the ruins, and that town eventually developed into modern-day Guatemala City. The tour visits artifacts from Kaminaljuyu ruins now housed in the National Museum of Archeology.

Tikal Archeological Area, Guatemala

Moving on, the tourers visit a Maya archeological zone to the north of Guatemala, Tikal, home to one of the most powerful kingdoms of the Classical Maya Period (200-900 CE). The Tikal ruins cover an area of more than six square miles. Book of Mormon tours believes the area corresponds to the East Wilderness described in the Book of Mormon, where many Nephite cities were built.

Lake Atitlán, Guatemala

The next stop is Lake Atitlán, the deepest lake in Central America, and the Kaminaljuyu ruins themselves; the area around Lake Atitlán is populated by villages in which Maya culture remains prominent. Mormon tourers believe that Kaminaljuyu was settled by Nephi in the 6th century BCE, while Lake Atitlán has been proposed as being the Waters of Mormon, where the prophet Alma baptized hundreds of Mormons as described in the book of Mosiah.

Quetzaltenango, Guatemala

Quetzaltenango, “place of the quetzal bird,” is Guatemala’s second-largest city and was also originally a Maya settlement that was later taken over by conquistadors. It’s also home to Guatemala’s second Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints temple (the first is in Guatemala City). The trip to Quetzaltenango passes through an area that some Mormons consider the Valley of Alma, also described in the book of Mosiah.

Tapachula, Mexico

The tour crosses into Mexico, landing in Tapachula in the southeast of the state of Chiapas. The area was inhabited by the Olmec people, Mesoamerica’s earliest civilization, and the city itself was established by the Aztecs in the 13th or 14th century. This stop is the jumping-off point for several days in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Mexico, an area rich in ruins and locations thought to play an important role in Book of Mormon narratives.

Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Mexico

Tuxtla Gutiérrez is the capital and largest city in Chiapas. It was first settled in the Pre-Hispanic era by the Indigenous Zoque people before being invaded by the Aztecs, and later by the Spanish. The city itself likely dates to the 17th or 18th century CE. Ruins and archeological zones abound in the area: it’s home to Izapa and its engraved stele, believed by some Mormons to depict the Tree of Life described in 1 Nephi; it’s the area where Zarahemla is believed to have been; and its regional museum contains many pre-Classic Maya artifacts believed to be or to record Book of Mormon events.

Villahermosa, Mexico

Next on the agenda is several days in and around Villahermosa, the capital and largest city of the state of Tabasco. The city itself was founded by the Spanish in the mid-16th century, but the region is home to many Olmec and Maya archeological sites and monuments, including Palenque. For Book of Mormon geographers, the Chiapa di Corzo zone is believed to have been home to the city of Sidom, the Grijalva River along which Villahermosa sits may have been the River Sidon, and Villahermosa itself may have been the “land of many waters,” as detailed in the book of Mosiah. Tabasco is also home to La Venta, an outdoor museum where you’ll find several of the colossal stone Olmec heads that may or may not represent the Book of Mormon’s Jaredites.

Catemaco, Mexico

Catemaco is in the south of the state of Veracruz, and was also once dominated by the Olmec civilization. The route from Villahermosa to Catamaco is significant for Book of Mormon geographers for passing the area thought to be home to the Hill Shim, mentioned in both the books of Mormon and Ether. According to the Church, a figure named Ammaron hid the sacred records of the Nephite people in Shim, and those records were later retrieved and became part of the Book of Mormon.

Veracruz, Mexico

On to Veracruz: the largest city in the state of the same name, on Mexico’s Gulf Coast, founded by conquistador Hernán Cortés in the early 16th century. The state of Veracruz was originally home to several Indigenous cultures, with the Olmec being most prominent in southern Veracruz. As in much of this part of the world, the area later came under the control of the Aztec civilization before ultimately being taken over by Spain. It is home to multiple locations thought to be significant for the Book of Mormon, including the hill Cumorah where the final battle between the Nephites and Lamanites occurred.

Mexico City, Mexico

The final stop is Mexico City. Along with visits to local shrines and museums, tourers visit Teotihuacan, a Mesoamerican city about 25 miles northeast of the city first settled in 600 BCE and home to some of the most significant pre-Hispanic monumental structures, the pyramid Temples of the Sun and Moon. It was one of the largest settlements anywhere in the ancient world, with a population of 125,000+ at its height in the 4th and 5th centuries CE. There are competing theories as to why the city declined, but it eventually fell to the Aztecs. For Book of Mormon geographers, Teotihuacan may have been the city built by King Jacob, as described in 3 Nephi.

And it came to pass that several days hence, I found myself rifling through dusty bags of peanuts in a dimly-lit convenience store in the tiny tropical town of La Venta in southern Tabasco, ten miles from the Gulf of Mexico. We’d spent the previous two days in Villahermosa (aka “the land among many waters” described in The Book of Mormon, Mosiah 8:8) and on a majestic boat ride along the Grijalva River, a convincing candidate for the River Sidon. And we’d gone to a K-Mart and eaten exclusively at chain restaurants. Someday, I told myself, on a different kind of trip, I’d eat los tamales de Chiapas, steamed hot with pepperleaf and pumpkin seeds, and I’d drink pox and tascalate. The indigenous culture of Chiapas is rich and unique. The Book of Mormon tour wasn’t interested in any of it.

The store was called El Mormón, so let’s call this next chapter:

EL MORMÓN

The Hunt for Palatable Snacks — O.G. Lamanites — Deep Doctrine — Racist or Not Racist!?? — Truth Claims in America — In Which Everyone Smells But Everyone Pretends Not to Notice — Father Knows Best

We were tired and drenched in sweat. It was approximately one million degrees outside, and we’d spent over an hour traipsing through a lush expanse, examining colossal stone heads the height of human beings scattered like neolithic Easter eggs in the towering grass. At Blake’s urging, we’d stopped at every head, examining their rough countenances, their blunt-cut features, and ornately sculpted helmets with all the jibber-jabber gravitas of armchair anthropologists. “This guy sure looks serious,” Matt said. Or: “Wouldn’t want to meet this fella in a dark alleyway at night.” Old Man Earl, his shirt dark with perspiration, inspected the stones from every possible angle, snapping away on an old digital camera.

On the ride to La Venta, we’d watched a DVD that explained how Joseph Allen had made the connection between the Olmec people, a pre-Mayan civilization “discovered” by archaeologists in the mid-20th century, and the Book of Mormon’s Jaredites, ancient Near Easterners who sailed to America on barges and then, over time, turned wicked, their skin darkening as they turned their backs on The Savior. According to the Book of Mormon, the Jaredites were “large and mighty men” — a fact that did not strike Blake as a coincidence. Per Joseph Allen’s “The Jaredites and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec”:

Aside from the testimony of the Spirit that the Book of Mormon is what it claims to be (see Moroni 10:4–5), perhaps no other evidence supports its claim of validity as much as the twentieth-century archaeological and historical discovery of the Olmec culture in Mexico. Amazingly, scholarly proponents of the Book of Mormon’s claim to authenticity have done relatively little to capitalize on the impact of the Olmec culture for this purpose.1 On the other hand, Latter-day Saints in general are fascinated to learn about the strong correlations that exist between the Book of Mormon Jaredites and the ancient Olmec culture that lived along the Gulf Coast of Mexico… Some of the most striking parallels include the following:

— Both cultures enjoyed a high civilization during the same time period.

— Both collapsed in a violent internal struggle at the same time.

— Both were said to have come from the great tower at the time the languages were confounded.

— Both were described as physically large people…

(Absent from this explication was the fact that, in the 1940s and 1950s, wealthy Mormons helped to fund an archaeological foundation that embarked on digs in Mesoamerica to prove the historicity of the Book of Mormon. Brigham Young University would eventually take the lead in these digs, which came up short time after time, tanking its reputation. In subsequent decades, the university distanced itself from that generation of archeologists and scholars, including Joseph Allen.)

Before we entered the museum, Blake had passed a photograph from his evidence binder around the van. It was him, twenty-odd years or so ago — same khaki shirt, much younger face — his arms slung around two young men, one kind of short and one a bit taller. He’d pointed to the tall one. “The kid, there, the son of the museum guide? How old would you say he is?” He’d looked at us eagerly.

Amy shook her head, thinking. “Maybe nineteen?”

Blake smiled triumphantly. “That kid was nine years old.”

Matt had gasped. “No!”

“Yes! It’s hard to believe, I know. But the Jaredites are, as it says in the Book of Mormon, a large people.”

“Certainly not like the Hawaiians,” added Betty.

Now we were perusing the meager offerings of la tiendita El Mormón. The woman who ran the store was a member of the Church, Blake explained; she’d converted years ago, faithfully travels over an hour to get to the nearest temple.

Betty wanted to know if the woman had made progress in converting people in town. Some, Blake responded. He’d read that a lot of Church leaders had predicted that the pandemic would finally reveal God’s truth to the majority of people in the world, that the end of days truly was nigh. That hadn’t happened, unfortunately, but there were still quite a few member families in La Venta. Not bad for a town that just a decade or two ago, he said, was drenched with alcoholism and almost entirely evangelical.

Betty had sighed. “One day, maybe this entire town will come to know the truth.” Her voice brightened. “Never say never.”

The shop owner was middle-aged, with tired gray hair and pink plastic studs in her ears. She had dark, broad features and weathered skin. Did she identify as a descendant of the Jaredites? If I told her that I was Jewish, would she speculate that maybe our ancestors had been on the same boat?

I’d been thinking about this for the past few days. No! I’d been dying to scream at Blake and Matt and Old Man Earl when they went on and on about ancient Israelites, how the LDS church just loves The Jews. No, my ancestors did not sail across the Atlantic and merge with indigenous groups up and down the Americas. And no, you certainly don’t get to appropriate Jewish history as an element of your claim to moral and theological superiority. For a group who hates — hates — being misunderstood and depicted inaccurately by the media, Mormon leaders are awfully eager to tell other people the story of themselves. The Mayans, the Olmecs, the Jews: why do you get to replace our own histories with yours? No.

But then, if you’re asking for the version of this story that’s most resonantly true, I could just tell you this: That my whole time on that trip, trying to listen to Blake hold forth, I was struggling to pay attention. Because what I was thinking about was not the limits of history, or religion as cultural appropriation, or the evidentiary perils modern science poses to people to take the Bible literally. What I was thinking about was my recent falling-out with one of my closest friends, when I was in deep grieving after losing a loved one and she told me that I am too emotional, that there is something deeply wrong with my emotional engagement with the world. And how at first I’d believed her. I’d been raised to mistrust my innate perception of the world and of myself. And so when she told me who I was, I thought that it was true.

But that’s not a complete version either. Because if we’re being honest, we’d acknowledge that some days an experience might be about one thing, and on other days it might be about another. Perhaps the best way to portray an experience would be to tell it in many different ways, over and over and over again, rotating and rotating that prism of hindsight and interpretation. Perhaps the best way to tell any story would be to never stop telling it at all. Stories shift and slide over time, their meanings changing as their authors and their audiences navigate their understandings of the world; this is how it should be. Calcified stories are dangerous.

While the tourers five visited the Maya Palenque ruins to examine a panel of elaborately carved stone glyphs showing the lineage of King Chan Bahlum, who Blake has good reason to believe could be the Jaredite king Kish, I left them to wander Villahermosa’s industrial backstreets. I was looking for the other side of Mormonism in Mexico, to see how it had been so successful in absorbing so many — 1.5 million! — of the country’s disaffected Catholics. Mormonism is known as “the most American religion”; its members believe that the U.S. Constitution is divinely inspired, that God led Columbus to the New World so that Joseph Smith could find the golden tablets in upstate New York. So why is Mexico the country with the second-highest number of Mormons in the world?

In Villahermosa, the Temple is a pristine white palace towering above the chaos and the humanity of the city. Paired missionaries fill the streets. Everyone in these parts knows the Mormons, more than one resident told me. Just go to the poorest parts of the city and they’ll be there, making their rounds.

That afternoon, I met with María Elena López, an 85-year-old woman living in a working-class Villahermosa neighborhood who converted to Mormonism in 1957. Like so many Mexicans who wind up converting to Mormonism, López had grown up Catholic but felt disconnected from that tradition; missionaries’ explanatory narrative about the world was much more convincing. “Now,” she told me proudly, “I’ve known God for sixty-five years…I testify now that Jesus Christ was here in America, in this very area of the Americas. He was here, and he taught my ancestors.”

As we spoke, a daughter-in-law and two adult grandchildren wandered in from adjoining rooms. The home was a humble one, with well-worn furniture on a linoleum floor and cement walls adorned with portraits of family members and founding members of the Church. I wondered how today’s Church leaders justified the tremendous wealth they’d accumulated in the area — largely through the requirement that every member tithe 10% of their income — while López and others who’d planted the foothold in the region were living twelve people to a three-room house. And I asked her about what it was like joining the Church in the 1950s, more than twenty years before President Spencer W. Kimball received divine revelation that dark skin was not, in fact, a barrier to the priesthood and that, regardless of skin color, all men are equal. (Women still very much aren’t.) I thought of Old Man Earl knocking on doors in 1964, and how missionaries of that era were told that if they encountered a black person it wasn’t worth the effort to try to teach them anything. There’s a phrase that older Mormons still whisper among themselves: “White and delightsome.” Is this a phrase she heard a lot?

Her grandson Lehí interjected. “If I may.” He was a good-looking kid, with a coif of thick black hair, just back from his mission in Tijuana. “When el Señor divided Nephi and his people, the color of their skin was the curse he put on the people who didn’t do the right thing. So it was a manner of differentiating the people who weren’t going to accept Him, his gospel. Who rejected him.” He spoke slowly, deliberately. He’d practiced this. “This was the way the Nephites knew who was following the gospel and who wasn’t, so they wouldn’t mix.”

He’d looked at me carefully. “The curse wasn’t skin color, the curse was being apart from God.”

He paused, looked at his mother and his grandmother beaming at him. “I’m being sincere here. I am—” He switched into heavily-accented English. “I am brown skin.” Back to Spanish. “I am Lamanite. I am proud of that. That is to say, I have the gospel, and I am very happy.” His voice deepened, slightly, and took on a more authoritative tone. “The truth is, Emily, I identify with you a bit. Because I also love history. I love archaeology.” He pointed to a bookshelf with a stack of leather-lined books on the sloped bottom shelf. “Those books over there are histories of the Church. And those there are Mexican history.” He took a deep breath. “I was raised Mormon, right? But I can tell you that I wouldn’t be one of those people who, if I’d been born Catholic, would follow the Catholic Church just out of tradition. Because I’m a person who likes to research, who likes to do things out of my own certainty. And I know that this is my church. I have no doubt, because the only person who knows everything is our Heavenly Father. I have a firm testimony that even if I knew nothing about history, if I only had a testimony, it would be sufficient to start on the right path.” Another breath. “And I want to tell you that I know that Jesus is the messiah and he is our savior. I know this clearly. It’s like I’m seeing this with my own eyes. I know that God exists, that he is speaking clearly, and he is saying that the most beautiful church is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”

He smiled at me. But I understood that he hadn’t even really been talking to me: he was talking to himself. A returned missionary once told me that the real reason the Church sends sheltered 19-year-olds away for two years isn’t to recruit new converts — it’s to make sure that those kids don’t leave the fold. Keep them busy from dawn to dusk. Don’t let them form bonds with anyone who might threaten their beliefs. Give them a script to repeat, and don’t let them stray from that script. Avoid tricky topics, like the location of Zarahemla or Kolob, the star nearest to God’s throne. And for Pete’s sake, don’t let these kids on Google. When you pair them off, make it clear that if they see their partner stray from the path they must report the transgression to the proper authorities. Rotate their companions every six weeks so they can never gain each other’s trust. And then make it understood that if they do all this, they’ll marry beautiful, dutiful, virginal women, and they’ll be a whole lot more likely to make it to the celestial kingdom.

Lehí beamed at me. “I’d like to invite you to investigate this for yourself, to have a conversation with Heavenly Father. You can ask him your questions yourself. You already know that this is our desire, but it should be your desire, too.”

from “LDS Church Charting Rapid Growth in Mexico”

by Jonathan Clark, El Universal

November 29, 2005

Gabriel López González was 14 when the first group of missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Mormons, arrived in his Mixe Indian town of San Juan Guichicovi, Oaxaca. He was immediately impressed.

“The missionaries wore neckties, and I had never seen people wearing ties,” he recalled.

Gabriel followed the missionaries as they knocked on doors in the community, and when they struggled to communicate with the Mixe-speaking locals, he stepped in as translator.

He continued in this capacity for four more years, and as he spent more time with the missionaries and listened to their message, Gabriel decided to convert. He wasn’t alone. Today, the town of 28,000 inhabitants has a thriving community of some 200 Latter-Day Saints.

“I think at first, like me, people wanted to know the missionaries because they wore ties,” Gabriel said, when asked to explain the church’s appeal in his hometown. “But as they heard more, they became more interested in the teachings and began to realize that it was the truth.”

Thanks to converts like Gabriel and his neighbors in San Juan Guichicovi, Mexico now has the second-largest Mormon population in the world, after the United States. And it continues to grow. In 1990, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or LDS, counted 617,455 members here. Today, it reports a membership of 1,037,775: a 15-year growth of 68 percent. In Mexico City alone, LDS officials say they are adding 1,000 new members each month.

Church leaders say that Mexico and Mormonism are a perfect match; their spiritual message connects well with Mexicans, as does their emphasis on the family, a healthy lifestyle and Jesus Christ.

“I think one of the reasons the church has grown so much in Mexico is that this a culture that has had a certain inclination towards the spiritual, ever since ancient times,” said Tomás Hidalgo, LDS spokesman in Mexico. “That is a crucial factor that allows people to feel the influence of the Holy Spirit and receive the message brought to them by the missionaries.”

Independent analysts point to the Mormons’ tenacious recruiting efforts and suggest that they and other upcoming religions are benefiting from a growing dissatisfaction with the dominant Roman Catholic church.

And it came to pass that toward the end of our journey, no less than an hour after descrying that Hill Shim on a malodorous hillside smack in the middle of nowhere, did we arrive at our hotel, with posteriors benumbed and no slight amount of hanger. The last leg of our journey had been defined by tedium punctuated with tremendous incident; at the border between the states of Tabasco and Veracruz, we had been interrogated by heavily-armed agents of the state, men with thick mustaches asking for papers upon papers: visas, passports, letters from government officials who did not exist.

Watching these agents from the passenger-side window — their wide-stanced machismo, their self-important smirks — I’d thought of my reporting among Central Americans who’d migrated up through Mexico, and the kidnappings and rapes and killings in cold blood they’d suffered at the hands of men who wore these badges. And that here I was, coming face-to-face with them for the first time while being driven in an air-conditioned van with tinted windows alongside a crew of geriatric Mormons, listening to a podcast and sucking on a lollipop.

Betty and Old Man Earl were fast asleep, their heads tilted back, their mouths agape. Amy was looking anxiously from Blake to the agents and then to Jesús, folding and refolding her hands in her lap. Matt seemed to be having the time of his life. He was staring in awe at the border officials, bringing handfuls of peanuts to his mouth. He took out his phone, snapped some pictures, began to type. I imagined the texts. We met Mexican border guards!!! They had armor on their trucks!! And automatic rifles!!!

That afternoon, we were in the lakeside town of Catemaco at a long narrow table at a hotel restaurant a few yards from the pool, where children were splashing loudly and a man in a fading Speedo tossed a rotation of shrieking toddlers high into the air. A band of skinny cats ran by, chasing a rat with half a tail. It was three days before the end of the trip, and the group’s energy was at a nadir.

We placed our orders: seafood for the mormones five, more beans and rice for me. “I just can’t imagine it,” Betty said, looking me up and down. “Imagine coming all the way to Mexico and not even ordering the fish.” She shook her head sadly. I managed to not say what I really wanted to: Imagine coming all the way to Mexico and managing to not care about talking with a single Mexican. Meanwhile, Blake and Matt rehashed the morning’s events. “Imagine if they treated people like that at our borders just because of their skin color. We’d never hear the end of it!”

In my head, I began to plan this meal’s place in my story, as a kind of stand-in for everything there was to say about Mormonism’s decades of strong ties to the Republican party, the ways that seeming to come in contact with the world (by, say sending adolescent missionaries to Mexico, or elderly ones to Hawaii) had proved to be an ingenious way to avoid actually engaging with anyone whose perspectives or experiences might challenge their own. Telling a story — about a culture, a history, about who your country is and why — is much easier than engaging openly and vulnerably with the world outside ourselves. All narratives are political, whether or not we’re aware of the purposes they serve.

And then the waiter approached the table, carefully balancing our laden plates on his forearms. He handed me my meal: a pile of white rice, a pile of beans, some gray-green vegetables sliding around in a sad little dish. I thanked him and put it down on the table.

Matt looked at my plate, then at me.

“You don’t eat meat, do ya, Emily?”

I shook my head.

“And why is that?” He seemed genuinely interested.

“Well—” I never know how to answer this question. There’s always what I want to say — the truth — and then there’s whatever version of the truth I respond with, depending on the person, depending on the context. “It’s… for ethical reasons.”

“And what are those?”

The whole table was looking at me now. It was a new feeling. I realized later that, aside from that first night, when they’d asked me how I’d first gotten interested in Mormonism, it was the first time they’d expressed any curiosity about me.

I paused. “I don’t want to participate in causing suffering to animals.”

Matt nodded, satisfied with my answer. “Yes, that makes sense.” He was studying me. “And that’s a valid reason. I respect that you act on your values.”

I nodded, unsure of what to say next.

The others had turned their attention to slicing up the fish on their plates, but Matt was still looking at me. “You know,” he said, after a moment, “I do respect that. I do.” He smiled at me kindly, as if this whole trip I had been waiting desperately for his approval and now here he was, beneficently bestowing it upon me.

But I was moved, truly, to a degree that surprised me. Only later did I understand why: It was the only time over the course of the entire trip that I’d been perceived by anyone with anything even resembling respect. It wasn’t complete, of course: it’s not that Matt respected me, only that he’d decided that living in accordance with one’s values was something to be respected, and thus that he gave weight to this particular narrative of this particular decision. But on a trip where every story I’d told about myself was met with wariness, with derision, with outright condescension, this one small gesture — this nod to my ability to tell my own story in my own terms — felt like a triumph.

In Villahermosa, I’d had dinner with two missionaries I’d encountered by chance on the streets: Elders Jack Doughty and Mitchell Bezzant of Wrentham, Massachusetts, and Highland, Utah, respectively. I was curious about a lot of things: their experience at the Missionary Training Center, which subjects they were and were not allowed to broach with potential converts, their methods of selecting which neighborhoods to trawl. Elder Doughty showed me the app they used, with a detailed map of every neighborhood they’d visited: the gray dots were people who weren’t interested. The yellow docs were investigators, the people in the process of studying the gospel. And the green ones were converts, points for the missionaries on their celestial-kingdom qualifying sheets. There were more than a handful of green dots spotting the region.

“It’s clear — it’s clear that you’re talking about the gospel a lot. And I’d imagine that you’re probably thinking about it a lot more, too,” I started. Elder Doughty, holding a heavily-laden chip, nodded vigorously. Elder Bezzant looked at him, and then he nodded, too. “Has your understanding of it changed?”

Elder Doughty swallowed. “Oh, absolutely,” he said. “It’s become more personal.” He paused. “It’s become a lot more true.”

I nodded. “So that’s something that the Church focuses on a lot, the idea that the Book of Mormon is ‘true.’ What does that mean to you? The idea of something being true?”

“I… I’d have to think about that,” Elder Doughty said after a moment.

Elder Bezzant, who’d been silent thus far, spoke up. “The thing about the Book of Mormon is that… the only thing you can get from this book is, like, good things.” He paused. “Like, it’s like it’s just directly from God, is what they’re saying is true.”

That was a definition — clear, concise — that I hadn’t heard before. I told him that. “So that’s been something that I’ve been thinking about a lot on this trip,” I said. “This idea of things being translated. The leader of my tour is sort of translating Mayan history, being like, Well, here’s another way to see it. And with the Book of Mormon itself, translation, from Ancient Egyptian to English, is such a key aspect of that history.” I paused, swallowed. “And the ideas of truth are related. Because if you translate something between languages, there are always multiple ways of translating something, and many of them can be correct.” Elder Bezzant nodded. Elder Doughty was looking at me a little differently now: a little more closely, a little more skeptically. “And if you asked everyone on my bus to give an account of what we did today they’d all be different, but they’d all be true.”

Elder Doughty nodded. “True accounts.”

“Right. So I’ve been thinking about how that relates to the Mormon idea of truth. It’s talked about so much, but I suspect it means different things to different people. So I’m curious about what you said about truth coming directly from God. Because that wouldn’t necessarily preclude there being multiple truths, right?”

The elders looked at me in silence and then, after a moment, Elder Doughty talked about the importance of reading the Book of Mormon, of directly beseeching God with true intent. “We have a testimony that anyone who asks God whether it’s true will receive an answer,” he told me.

I nodded. “And have you ever met anyone who read it and then was like, ‘Nah, not for me?’”

Elder Doughty smiled. “I mean, like, they’ve said they’ve read it. But then, if you’re like, ‘Well what do you think about this part?’ then they won’t know how to answer.” But the people who have read it, he told me — the ones who have read it for real — you can just tell. It changes them immediately.

“You’ve probably heard that the Book of Mormon is the keystone,” he continued. “Like, if that’s not true, then none of this is true, you know what I mean? Like, we say it’s the keystone because, you know, like, in an arch, there’s that wide angular piece that supports everything else. And if that stone cracks or breaks, it loses its structural integrity.”

from churchofjesuschrist.org

…With a little luck, the presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon just might help to explain its repetitious, roundabout way of saying things, which has made it hard for many people from Mark Twain on down to read and enjoy the Book of Mormon.

Thus, the presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon would reveal new ways in which the Book of Mormon is true to itself, true to its general cultural origins, and truly a remarkable piece of religious literature in its own right.

And it came to pass that, on the last night of the journey, Old Man Earl realized that he’d lost his camera. He’d had it at La Venta, that’s for sure: he’d taken all those photos of the statues, then gotten dozens of photos from a towering peak we’d taken great effort to climb. He’d had it when we’d stopped at the Hill Shim, where he’d asked me to take photos with it: first him alone, then him and Betty, then all of us together, even me. But then the group had gone to a temple where no non-Mormons — and certainly no cameras — are allowed. And somewhere along the way, Old Man Earl had lost his method of memorializing our great adventure.

He and Betty had spent nearly $10,000 to take this trip. And Old Man Earl was nearly eighty, the length of his allotted time on earth known only to the almighty. His spirits seemed high, as usual, but I could tell that he was upset.

Betty patted him on the shoulder. “It’s a good thing everyone on the trip was taking photographs this whole time,” she was saying. “It doesn’t have to be a tragedy for the ages, dear.”

But Amy was shaking her head. “It’s not the same, Earl. You took such care with those photos. And none of our pictures will convey your experience on this trip. It’s a real shame. It really is.”

Right before I met them at dinner, my companions had gone through the Veracruz Temple, another massive, gleaming white monument straddled awkwardly amidst the busy city. Only Mormons who’ve been approved by their bishops are allowed to participate in Temples’ most sacred rites, and revealing them is considered worthy of celestial banishment. But they’re allowed to talk in broad terms about what goes on inside. One of the main activities is baptizing the dead. They take the names of people who died without having the opportunity to accept that Mormonism is the One Right Way and perform rites for them, to make sure that they get a shot at the celestial kingdom. It’s something the Church has gotten in trouble for in the past, when members used lists of Holocaust victims to perform posthumous baptisms. They baptized Anne Frank. More than once.

Elements of that are absurdly offensive to many people, of course. But in the end the only people served by that action are Mormons themselves. Because unless you put some stock in the power of that story, unless you believe that the baptisms do something, the only people served by the story are the people who are telling it.

So if someone were to ask me for the headline for my time with Book of Mormon Tours, I might try this:

Atheist Completes Mormon Tour, Still Atheist

And there’s a less definitive version that’s just as true:

Emily FOX Kaplan Goes Looking for Something, Not Sure If She’s Found it

But if you asked me to summarize the experience of anyone else on my tour, I couldn’t. Theirs is not my story to tell. Just like, when it comes to my friend who broke my heart, only I can tell my story, and only she can tell hers. If she accepted my version, she’d have to face the reality that the story that she’s been telling herself about how the world works is wrong — and “if that stone cracks or breaks, it loses its structural integrity.” She’d have to accept that she has caused pain, to herself and to others. That our right to tell stories ends at the borders of our own identities.

Storytelling is humanity’s fervent, sometimes transcendent, sometimes lacking attempt to make meaning out of chaos. That’s what all storytellers do: Mark Twain, Old Man Earl, me. It’s what Joseph Smith did in his famous book, and at the end of the day, The Book of Mormon is a remarkable work of literature. It is a mish-mash of plots, of voices, of referents and registers. It is sloppy in places, profound in others.

For Blake, for Matt, for Amy and Betty and Old Man Earl, it confers tremendous meaning. For María Elena, for her grandson Lehí and those adolescent elders who walk the street of Villahermosa — for the millions of people who have decided for themselves to identify with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints — the stories of the Lamanites, of the Nephites and the Jaredites, provide a history that grounds and instructs them.

The Book of Mormon is more than the sum of its parts. It does what all good stories do: it tells a story that resonates, that teaches us about the world. That is beautiful.

That is all. And that is enough.

Emily Fox Kaplan lives in Brooklyn. Her writing and photography have appeared in publications including The New York Times, The Atlantic, Harper’s, Guernica, and The Washington Post Magazine. Before becoming a journalist, she taught elementary school in Boston and the Western Highlands of Guatemala. She is currently at work on a book of reported nonfiction on Protestant Christianity in contemporary America.

Axel Rangel García is an award-winning Illustrator based in Mexico City. He collaborates with publishers in Mexico and internationally, including The Washington Post, POLITICO Europe, The New Statesman, WIRED Middle East, Columbia Journalism Review, Blockworks Group, Arab News, Forbes Mexico, and Macmillan Publishing, among others.

Editing and layout: Michelle Weber

Fact-checking: Matt Giles

Copyediting: Soraya Roberts

More great reading

from Pipe Wrench no. 8

In Unto the New Jerusalem

Art historian (and ex-Mormon) Darren Longman takes a critical look at Ancient Mesoamerica in LDS visual culture.

There Are Lots of Ways to Tell a Story

For cultural critic Laurie Penny, we need new models for the “community” part of “communication.”

Creating Visual Syncretism

Axel Rangel García incorporated layers of symbolism into his illustrations for this piece, and you can explore them one by one.