Bindiya Rana had two lifelong dreams: for the khwaja sira to live fully and freely, and to personally perform pilgrimage in Mecca. When the first began to become a reality — between 2009 and 2012, Pakistani courts ruled on cases that ultimately granted a range of rights to gender-nonconforming people and in 2018, the Pakistani parliament passed a landmark gender-identity law— she turned her attention to the second.

You’d think it would be easier to make a trip made by millions of Muslims each year than to knee-cap the gender binary underpinning your country but, despite the presence of gender-ambiguous people in early Islamic texts, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia does not recognize gender-fluid people and only begrudgingly grants them entry — 2017, a Pakistani migrant working as a women’s tailor in Riyadh was arrested after a police raid; wearing women’s clothing, the migrant was later found beaten to death in custody. That the identity documents Bindiya had fought so long and hard for — the ones that allowed her to tick a box other than M or F — might impede her other dream broke her heart. Sabz gumbad waalay, you of the green dome, she’d pray and weep, addressing the Prophet Muhammad’s tomb in Medina, when will you summon me to your side?

In 2018, the divine summons came. After some string-pulling by activist friends, Bindiya found herself on a plane, eldest sister in tow, and then in Medina, where Muhammad is buried. It was summer, hot and dry; the tiled floor of the mosque was scorching, but she fell to her knees and kissed it anyway. She made her way towards the filigree gates behind which lay the grave, but mosque guards waved her away — that area was reserved for men. Crushed, she begged and pleaded until her sister, terrified authorities would lock them up, dragged her away.

No matter: Bindiya went back to the hotel, grabbed a pair of scissors and chopped off her hair. Bundling what remained into a prayer cap, ignoring her sister’s yelps, she marched back to the mosque for evening prayer; now presenting as masculine, she sailed straight past the guards, folded her arms over her chest, and began to pray. She prayed until strands of her hastily-cut hair began escaping the confines of her cap, until the men around her started pointing and muttering, hurma, woman. You keep saying hurma hurma, Bindiya thought to herself. I’ve done what I came to do.

A year later, Bindiya’s hair has grown back and her roots need retouching so we are stuck in evening rush hour, inching from one end of Karachi to the other. Surely there are salons closer to home where Bindiya’s hair can be fixed, but she had an allergic reaction to the chemical dye at the last place, red splotches everywhere, and the proprietor of this salon, Bebo, has promised she will only use the good, organic stuff. Bebo personally sent the car for Bindiya, and now keeps calling to make sure she isn’t lost. Mummy, are you in the car now? Mummy, call me when you reach Gulshan. Give the phone to the driver, mummy, I’ll explain the way.

The driver is visibly vexed by these interruptions, because Bindiya is in the middle of telling me a story and he is discreetly hanging on to her every word, no longer bothered that she’s smoking inside his car. When Bindiya tells a story, she goes all in, does all the voices and everything, and right now, as she talks about that moment when things came to a head and her family discovered she was living life as a hijra — a once-innocuous term for third-gender people in South Asia, so abused it has now curdled into a slur — as she describes that moment, she acts out all the parts: her father’s embittered shame, her elder brother’s seething rage, her mother’s tears, everyone else’s distaste. She tells this story unprompted because this is what everyone always wants to know, all the foreign journalists gobsmacked by her existence in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, all the cub reporters embarking on their first “human-interest” feature. Tell us all the ways in which you have suffered.

“It’s like trying to stuff a camel into a rickshaw,” Bindiya proclaimed later that evening, pacing the salon as she explained this predicament. Bindiya the bereft teenager is very much a creature of the past; this is the Bindiya who contested legislative elections, who coordinated the rescue of 300 kidnapped babies, who acted in a soap opera, who with other elders leveraged the state’s pitying paternalism into a landmark law — Bindiya, madar-e-khwaja sira, community matriarch, whose entire existence has been one big nose-thumbing at the notion that to be khwaja sira automatically means living a diminished life.

Outside, the call to prayer crackled from a nearby mosque, punctuated by the slamming of shop shutters. Inside, Bindiya’s roots were wrapped in foil; a cutting cape fluttered from her shoulders as Bebo clucked after her, dye-dipped knife in hand. Mid-stride, she turned around.

“But you know what? The other day, I saw this video: these men bought a camel to slaughter for Eid and took it home in a rickshaw. Can you believe it? A whole camel! In a rickshaw!”

She arched her eyebrow. “So you see, it’s not impossible.”

Once upon a time, before rickshaws or cars, before Pakistan existed as a state or a dream, before British companymen clomped into South Asia and siphoned off its riches, gender-fluid people were important figures in royal courts — political advisors, administrators, military generals. But there was a catch: in order to be a khwaja sira, as the most senior of these princely employees were known, you had to dress a certain way. Most complied; who wouldn’t want that cushy job? But one refused. No one would tell her what to wear.

“That was our ancestor,” said Sapna as we sat on the floor of Bindiya’s bedroom making small talk while she puttered about in the kitchen, assembling a fruit salad. Sapna, who is in her late twenties, lives in an apartment downstairs with her biological mother. “That’s why we’re known as the naa-guru caste. From the guru who said no.”

On the Indian subcontinent, including the region that would cleave away and become Pakistan, hijras — the pan-Indian moniker for this particular category of nonbinary people – made their living going door-to-door singing, dancing, and conferring blessings on newlyweds and newborns. This practice, badhai, is rooted in millennia-old mythology. In some versions of the epic Ramayana, the exiled god Ram instructs the “men and women” of his kingdom to disperse rather than mourn his departure. Upon his return 14 years later, he finds his hijra devotees, who are neither men nor women, rooted in place, waiting for him. Touched by their devotion, he imbues them with mystical powers.

Once upon a time, before rickshaws or cars, before Pakistan existed as a state or a dream, before British companymen clomped into South Asia and siphoned off its riches, gender-fluid people were important figures in royal courts.

Recent scholarship scrambles this historical picture ever so slightly: hijras in precolonial India were farmers, weavers, shopkeepers, and traders and performers and badhai collectors, something downplayed in colonial accounts that take great pains to depict hijras as beggars, vagrants, and loafers. Generations of hijras lived together, with gurus passing on hijra history and culture to new initiates; when they grew too old to work, their chelas cared for them. It is unclear why no such networks evolved for people assigned female at birth — the archives are silent on whether they ever existed — but one explanation may be that acceptance of gender fluidity did not necessarily preclude gender hierarchy in South Asia. To live a hijra life still meant moving away from male privilege, which means that you needed protection. There was safety — and community — in numbers.

These networks would prove crucial as the British consolidated their hold in the region in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. British India was not a settler colony, like Australia or the United States; on the subcontinent, colonial overlords were more focused on exploiting indigenous labor than on wiping out local populations. The hijras were the one exception: their existence so unsettled the British administration, upending their notions of reproductive sexuality and patrilineal descent, that it resolved to bring about a gradual extinction of “eunuchs,” as the British referred to hijras. They were an “outrage to morality,” perpetuators of an “organized system of sodomitical prostitution.” Between the 1850s and 1870s, prompted by a string of court cases, northern India convulsed with a moral panic about hijras and the threat they posed to young boys as alleged kidnappers, castrators, and pimps. One of these cases involved the murder of a hijra guru — Bhoorah, whose head was nearly entirely severed by a scorned ex-lover — but still, the trial became an opportunity to denounce the community. Other cases involved kidnapping and castration charges; even when the courts acknowledged that adults had been willingly castrated, they ruled that consent was not an acceptable exemption from prosecution because, in one court’s opinion, castration was “not for the benefit of the person consenting.” (It’s worth pointing out that you didn’t have to be castrated to join a hijra community: some members were born intersex, while most others felt they possessed a feminine soul regardless of genitalia.)

From 1865 until the early twentieth century, the colonial government in north India tracked its progress in causing “eunuchs” to “die out,” convinced its strategies were succeeding. (In fact, the community had become adept at evading surveillance, even using a coded dialect still spoken today, and policing at the local level was uneven at best.) They did not succeed, obviously. The British were booted back to their island in the middle of the twentieth century, where today Victorian-era ideas about biological sex are being reincarnated under obfuscatory new names like “gender-critical feminism.” Meanwhile, in Pakistan, the khwaja sira community has become increasingly visible: over the past half or so decade, headlines celebrating the country’s first trans model or doctor or news anchor have become commonplace and this year, Joyland, a love story starring Pakistani trans actress Alina Khan won a jury prize at Cannes. These firsts also underline the blow dealt by colonialism—who knows what khwaja sira life would have looked like without that rupture? But Sapna’s account, about the guru who said no to curtailing of freedom even prior to the British, complicates this line of thinking, too. We rejected the state, it seems to say, before it rejected us.

Sapna’s own story is complex, dodging a tidy narrative with each swerve. Assigned male at birth, when she came out, her mother — who’d birthed six daughters before her — begged her to reconsider. In most Pakistani families sons are prized possessions, and privileges accrue not just to them but to their mothers. Bahut aas aur umeedain lagi hui hain tum se, her mother pleaded, I’ve pinned all my hopes and dreams on you. Sapna tried her best to live as a boy, but by the time she was a teenager she’d begun working as a small-town dancer. Over the past fifteen years, she has had a number of gurus. The one in Punjab taught her how to dance. The one in Karachi taught her how to go door-to-door bestowing blessings. And Bindiya, her guru now, helped her maintain familial ties, also encouraging her to seek alternative livelihoods. “She made my family understand that if they wanted me in their lives, they’d have to accept me as I am. My sisters, they’re all very sensible — they said to me, do whatever you want, just don’t break ties with us.”

Badhai was how Bindiya met the khwaja sira who would become her family: dancing with them at her biological brother’s wedding. She was thirteen going on fourteen and lived in Lyari, one of Karachi’s oldest neighborhoods, a tangle of narrow lanes and scalloped power lines, and it turned out the dancers lived a few streets away. The following year, her brother had a baby boy and the khwaja sira returned to celebrate; this time, details were exchanged and she began sneaking out to meet them. The elder khwaja sira fussed over her, chiding her for eating out, rushing to feed her themselves. To Bindiya, their food tasted just like her mother’s. By the time she was sixteen she’d moved out.

In early 2009—winter is peak marriage season in Pakistan—police raided a wedding party on the outskirts of Islamabad and arrested a handful of khwaja sira dancers. Private performances are one of a very few ways third-gender people are able to make a living, but these mostly all-male functions — teeming with handsy, drunken, patrons who, inexplicably, love celebrating by firing guns into the air — are far from easy money. Events are often disrupted by police, which is not strictly legal but happens anyway, with detained dancers being harassed, assaulted, and blackmailed by law enforcement itself.

News travels quickly in khwaja sira networks. Within hours, a hundred or so people, led by prominent local guru Almas Shah (also known as Boby) had convened at the police station to demand the release of their sisters. They screamed and clapped and shook their fists; flower pots reportedly flew through the air. The alarmed police superintendent released the dancers and promised to sanction the offending officers, but the protestors had kicked up enough of a fuss to find themselves in newspapers the following day. The news report caught the eye of one Muhammad Aslam Khaki, a local professor of Islamic studies with a penchant for filing public interest litigation, who had successfully challenged Pakistan’s penalties for drinking alcohol and prohibition on conjugal visits for inmates and, for reasons too convoluted to explain, threatened to bring a blasphemy case against the federal government itself. In this instance, Khaki’s petition to protect this “most oppressed section of life whose fundamental rights are infringed by their parents, society, and also the government” dovetailed perfectly with the activist tendencies of the Supreme Court at the time. “The Chief Justice put personal interest and effort into this case,” Khaki later said. “I didn’t have to do much research or lawyering, he passed order after order on this issue.”

Court proceedings in Pakistan are carried out in English — another gift of colonialism — although not everyone is proficient in it. But local languages present their own challenges. In Urdu, for instance, everything has a gender. I am eating a banana is not a gender-neutral sentence, and its precise language will change depending on how the speaker identifies. In most formulations, even the damn banana has a gender (male). To exist outside a male-female binary is to repeatedly crash against the limits of language, spurring the creation of new alternatives. Trans, TG (shorthand for transgender, bequeathed by acronym-prone NGOs) third gender, hijra, khwaja sira, khusra, moorat — the last an amalgam of mard and aurat, man and woman, according to one explanation, although the word independently means “idol” — all figured in my conversations, depending on context, although I knew I could only use some of them. (In India there are efforts to popularize kinnar, a term with roots in Hindu mythology that some activists fear is an attempt to absorb the community into an ascendant right-wing Hindu nationalism.)

Khaki versus Rawalpindi, though well-intentioned, teems with Victorian terminology like “castrated males” and “eunuchs,” the latter transcribed for posterity by an orthographically-challenged court stenographer as “unix.”

But the law is designed to codify and contain — it hates ambiguity — and it demanded one official name. Eunuch, suggested the government; no, no, no, balked the community. Hijra was a common moniker but had lost all respectability, wielded as an insult in playgrounds and parliament alike. So the community dusted off the Mughal-era epithet of khwaja sira, which had fallen into disuse. In a self-consciously Muslim country like Pakistan, the term also invoked a certain spirituality: khwaja is an honorific for Sufi teachers. (“And we’re all adherents of Khwaja Gharib Nawaz,” adds Bindiya, alluding to a prominent 13th-century Sufi saint.)

The next hurdle took longer to clear. Exactly who, officials demanded, counted as khwaja sira? The court’s sympathies were predicated on an essentialist understanding — that they are all intersex — even though the khwaja sira describe themselves in more abstract terms, as people possessing feminine souls. Paying no heed, the government announced that if affirmative action in the form of, say, public-sector jobs was to accrue to the benefit of the community, imposters had to be weeded out. It announced mandatory medical examinations.

Outraged, Bindiya and medical student Sarah Gill petitioned the high court to scrap the policy. Always game for some drama, Bindiya drove her point home by confronting officers at the head office of NADRA, the authority in charge of national identification. “A team of doctors is on its way,” she proclaimed. “I have reason to believe there is a khwaja sira among you, so you must all undergo a medical check-up.” She smirked at the recollection. “When the sword dangles over your own head, when your own clothes are taken off, then you understand what another person goes through.”

This appeal to privacy proved surprisingly effective. In 2018, when Pakistani parliament began codifying the Supreme Court’s directives into anti-discrimination legislation, the definition of gender enshrined into law was, by any standard, a radical one: “gender identity means a person’s innermost and individual sense of self as male, female, or a blend of both or neither, that can correspond or not to the sex assigned at birth.” There was no more talk of medical examinations. Now, according to the state of Pakistan, your gender was what you said it was.

Bebo, who grew up middle-class in Mirpurkhas, a city three hours away from Karachi with the rhythms of a much smaller town, always knew she was transgender, though she wasn’t open about it. “As a teenager, all I knew was that everyone kept yelling at me for watching TV and listening to songs by Sridevi,” she says as she prepares Bindiya’s dye, referring to a 1980s Bollywood queer icon. Zehrish, another activist who works with Bindiya, grew up in Karachi on a diet of grisly tropes: that they kidnap little children and forcibly castrate them, that they have strange burial rites. “My mother would scare me when I was little,” she told me. “My mother created this great big phobia in my mind — if you act like them, they’ll take you away — and so, if they were approaching, or even just passing by, I’d run away from that street.”

The Supreme Court leaned into the ignorance. Pointing to a similar scheme in the Indian state of Bihar, it suggested recruiting khwaja sira as members of municipal bill and tax recovery teams — the court subsequently instituted a two-percent quota in certain Karachi neighborhoods. The unstated, problematic rationale was that residents who hadn’t paid their gas, sewer, or electricity bills wouldn’t want disreputable khwaja sira openly knocking on their doors and they’d hastily cough up their dues. Still, the community was delighted. Bebo was among the first recruited. It was a minimum-wage contract job, but a government job all the same. “The [old collection] team would never meet its targets,” Bindiya beamed. “When they joined, they exceeded their targets.”

Khwaja sira communities didn’t always try to dispel the fear and suspicion, instead using it as a means of keeping the world at bay. For a long time, and to some extent still, khwaja sira communities were notoriously private — historically, under the beady eye of a punitive colonial state, they’ve had good reason to be. That paranoia extends to any perceived threat that will bring the power of the state to their doorsteps. When Bindiya and other activists began engaging with the state, they faced great blowback from within the community, especially from khwaja sira elders. “The prominent gurus, they’d criticize us, they’d say you’re giving away all our secrets,” said Bindiya.”You’re stripping us, our way of life, naked.”

In 2017, when “khwaja sira” was included as a category in the Pakistani census for the first time, their official numbers were listed as 10,418 in a country of 208 million. Activists from the community decried this as a gross undercount — their own estimates range between 300,000 and 500,000 — and while this is likely due to ongoing discrimination, with census workers or family members forcibly listing them as men, some khwaja sira chose not to partake in the census or to officially identify as such. One reason is that coveted pilgrimage to Mecca: there’s the lingering anxiety that a nonbinary ID makes it harder to travel to Saudi Arabia. Others fear that one day, as in the past, the state will use any and all information against them.

I had initially thought of Bindiya as the old guard among the khwaja sira, keeping the community tethered to its old ways, but it quickly became clear that she was viewed as an upstart among elders who did not wish to reintegrate into so-called polite society. The guru/chela system is predicated on an elaborate hierarchy, with carefully delineated rights and responsibilities; within it, Bindiya’s more of an incrementalist, chipping away where she can.

“When I’m in the community, when there’s a funeral or a gathering, I’m not Bindiya the activist,” she said. “I’ll clean an elder’s spitoon without batting an eyelid.”

Younger people are less tolerant of such hierarchies. In the past, trans women didn’t really have a choice other than to join the guru/chela community. “I became a chela when I left home because that was the only choice I had — I didn’t have a place to live. So it was kind of imposed on me; if you need to survive, you have to follow the system,” said Sarah, who is now the first openly trans doctor in the country. The support typically came with the risk of exploitation, with young people forced to work against their will or sold off to another guru or household — even though trafficking isn’t widespread within the community, it is still a serious problem, she says. “For instance, let’s say, I am someone’s chela. I have a good face, I dance well, I get lots of tips. You see me at a function and say ‘I want to make her my chela.’ And my guru will say, okay, she can be yours for half a million rupees.”

And since most traditional gurus know no other way of life other than sex work or dance, they tend to be skeptical of white-collar jobs — these are seen as precarious, susceptible to termination any day, not to mention difficult to come by. (Since the gurus get a cut of their chelas’ earnings, they have a vested interest in job stability.) “And that suspicion is extended to NGOs,” said Sophia-Layla Afsar, a trans therapist and artist. “The sort of work Bindiya does, that activists do, is seen as fickle because the thinking is: What if the government changes its mind? What if public sentiment shifts? You need to have a backup source of income in case your UNDP funding suddenly stalls.” (Last month, after this conversation, Layla’s hypothetical came to pass: UNDP announced it would not renew its contract with Bindiya’s community-based organization, Gender Interactive Alliance, which provides treatment and care to more than 1,500 HIV+ khwaja sira.)

Although the Supreme Court’s intervention had been predicated on an assumption that the community pursued certain work because no other option was available to them, the income from that work often exceeds what an entry-level government job can offer. Senior gurus often amass great wealth — Almas Boby, who led the protest that spurred the 2009 Supreme Court order, declared more than 100 million rupees in a 2018 tax amnesty scheme. Bindiya sometimes semi-dramatically bemoans her decision to pursue activism rather than live the life of a traditional guru: “By now, I would have had three or four buildings in my name, gold, a bank balance…”

Still, the community is changing, even if some would prefer it didn’t. Some younger gurus are less wedded to old ways, while others like Layla, who transitioned later in life, have opted not to be formally inducted into the system although, its very existence can be a source of solace. Layla, in her practice as a therapist, often comes across trans men who feel unmoored because there is no similar visible community to turn to. And even those within the khwaja sira community appear more comfortable in critiquing its internal workings. “Why should we hide our dark side?” said Sarah. “Everyone has it. What is true is true, we have issues too—we don’t want to be angels.”

We are stuck in Karachi traffic again, but today Bindiya is uncharacteristically subdued. It was a long day at the office and it left her feeling tired — and old. “Sometimes I console myself: The thorns that pricked our feet, that we painstakingly removed and set aside, at least our future generations won’t have to suffer those. But then I can’t help but think: what did I get from it all? Nothing but loneliness. When you decide to be an activist, when you commit to a cause, there’s a lot else that you give up. Those were my days to laugh, to have fun, to be carefree —”

She breaks off.

“Look — can you see those two?” Our car is stopped at a traffic signal, and she nods towards two moorats weaving their way through the tangle of cars. “Look at how they’re smiling and giggling as they’re asking for money. They don’t have a care in the world, they’ll go home and hang out with their friends, they don’t have to worry about interviews or meetings or anything the following morning.”

Then her tone sheds its wistfulness. “Look at that motorcycle wala, look at how he keeps turning around to ogle at them.” She watches him intently. “I feel great anxiety when I see this, immense mental tension. Even today my people are in the same position that they have been for so, even today they’re subject to the same lecherous gaze.”

By this time, the two moorats are at my window. One of them peers inside. She’s wearing fluorescent contact lenses.

Law and culture do not change at the same pace. Violence against the community is routine: by patrons, partners, police, and sometimes by other moorats, too. It is particularly rampant in the northern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; according to TransAction Alliance, a local rights group, nearly a hundred trans women have been murdered there since 2015. For a long time, this violence remained undocumented, much like the community itself. That’s changing— “I’ve seen the days when khwaja sira would be gang-raped by powerful men, who would shave their hair and lock them away in private jails for days. There’d be murders, hurried burials, no outrage, nothing,” Bindiya said. “Now there’s social media; when something happens, there are voices from all four provinces.” But the murders and attacks persist. Many say the increased rights and protections and the visibility that bring have been accompanied by a surge of violence against the community.

Bindiya pointed out the window at a high-rise residential building. “The people living in these buildings, they’re safe. At least they can sleep peacefully at night. There’s security, there are amenities. It should be so that everyone has these things, shouldn’t it? She sighed wearily. “When that will happen, only Allah knows.”

A few months before COVID-19 turned the world on its head, a dozen or so activists squeezed into Bindiya’s three-room offices to discuss a new initiative documenting attacks against khwaja sira across Pakistan and building better relations with local police, who often perpetuate violence rather than offer protection. The attendees began discussing a recent incident: a group of moorats had been arrested — on suspicion of panhandling or sex work, it wasn’t clear which — and at the police station, ostensibly to avoid being charged, had stripped off their clothes, alleging that the police had assaulted them. The consensus in the room was that these claims were false; the worry was that they had soured police sympathy, risking future cooperation.

In their fight for state recognition and social respectability, khwaja sira activists successfully deployed a narrative of choicelessness. In Pakistan, the argument went something like this: Because the state has so thoroughly disenfranchised us for something beyond our control, we are forced to live and work in ways that society deems unsavory. But there’s a catch in this strategy. As gains are made, there’s an accompanying expectation to become “respectable” subjects, even when some might wish to choose otherwise. Nor has Pakistan’s recognition of trans rights led to similar progress for other marginalized groups, be it sex workers or gay people (India, most notably, struck down its law criminalizing gay sex in 2018, a colonial-era remnant that is still in place here.)

As long as an identity is stable, it is not a threat to the state, explained feminist researcher and activist Afiya Zia. “In a Muslim context, khwaja sira are not necessarily a problem. You can change your gender, you can choose your gender, but at some point you must settle it — it must be stable. That’s why the state and the Islamic council didn’t have a problem with the transgender rights law. All it requires is stability, of the family, of all the usual conservative things. The state has a handle on it.” This is why having a single name and definition was so important to the courts. The law understands two genders, or three. It is less equipped to handle infinite variety.

This tension was evident in the room that day, both among the khwaja sira attendees — some of whom felt the urge to present themselves as a model minority —as well as other activists. One, the head of an organization for female sex workers, made the case that the khwaja sira, having wedged a foot in the door, had a responsibility to wrench it open for groups that remain criminalized. “You all have received legal rights, but sex workers haven’t,” she said, her voice vibrating with emotion. “You’re our seniors in that regard, so I must implore you to not forget them. Now that you have governmental reach, you must speak up for them too.”

This demand presupposes a security that the community doesn’t necessarily feel. Progress is rarely linear (this feels especially true these days, in a backsliding world) and for many khwaja sira, their hard-won gains still seem tenuous, the prospect of being yanked backed into an old story perilously close. After all, for all its insistence on precision, the law is an ever-evolving thing, subject to constant revision. For the 2018 law, activists successfully fought to include a radical definition of gender and within two years, it dodged a near-fatal blow from a conservative lower court. In 2020, a man sought to annul the marriage of his daughter to someone he claimed had used the 2018 law to identify as a trans man in order to legitimize what would otherwise have been an illegal same-sex union. The court ordered a medical examination— resurrecting that old battle — but before it could pass a binding order with implications for Pakistan’s legal definition of gender, the couple divorced of their own accord.

Not everyone wants surgery, and not everyone who wants it can afford or access it. (Gender-affirming surgery is currently available free of cost in one Pakistani province — ironically, the province where violence against khwaja sira is exponentially higher.) Moreover, there’s always the fear that this concession could lead to further losses—the state further restricting the rights of intersex people, for instance. On this point, Bindiya is unequivocal. “They say, some of you are fake, some of you get surgeries, some of you have beards. To which I say: This body has been given to me by my God. It is my kingdom — I can change it as I wish. If I need a medical check-up and a counselor to tell me who I am, that means I am not alive, I am not conscious.”

In Mecca, a key component of pilgrimage is tawaf, the seven circumambulations around the Kaaba; it demonstrates the unity of pilgrims in their devotion to God, invoking the orbiting motion of the sun and the moon. Seven was too few for Bindiya. “When someone has been thirsty for centuries, is craving just a drop of water and then they come across a river — they lose their minds,” she said. “I’d been yearning for this deedar, sighting, for eons and here it was before me.”

After tawaf, pilgrims perform sa’i, a ritual that involves traveling on foot between two small hills 450 meters apart — running, jogging, brisk-walking, whatever your capacity — in memory of Hagar, wife of Abraham, mother of Ishamel. Biblical accounts vary slightly, but in the Quranic version Muslims are familiar with, Hagar, left alone in the desert with her infant son, runs seven times between the hills of Safa and Marwa, desperately seeking water while her baby cries from thirst. Gabriel appears, sent by God, and strikes the ground with his wing: a spring flows forth. Millennia later, it continues to flow, even as the path between the two hills is now roofed, tiled, electrified, air-conditioned.

There are signs that tell you when sa’i, derived from the Arabic word for striving, commences; when Bindiya would pass one, she’d start sprinting. “The men near me would start running really fast too, thinking that if a woman could run this fast, so could they. They didn’t know I was a TG, a khwaja sira. My sister said, you’re making a fool out of these men! I said no, I’m energizing them. I’m reigniting their faith!”

This is the image that remains: Bindiya in the autumn of her full life, devout and determined; Bindiya, madar-e-khwaja sira, racing between two sacred mounds in memory of another mother, outrunning women and men and the categories that continue to shackle us all; Bindiya, whose feet will swell to twice their size as soon as she returns home to Pakistan, but who would do it all over again.

Now explore criticism, essay, poetry, and more from the people and communities whose lived experience informs the rest of this issue: transgender scholars, artists, and activists from around the world, centering on Indigenous people and people of color. They’ve all read the feature story, and these pieces are their contributions to the conversation.

Alizeh Kohari is a Pakistani journalist who divides her time between Karachi and Mexico City. Her reporting has appeared in Harper’s, WIRED, The Baffler, BBC and Reuters, and others. She is the inaugural Bruno fellow at Coda Story, where her project involves investigating authoritarian uses of technology in Pakistan, and a Persephone Miel fellow with the Pulitzer Center.

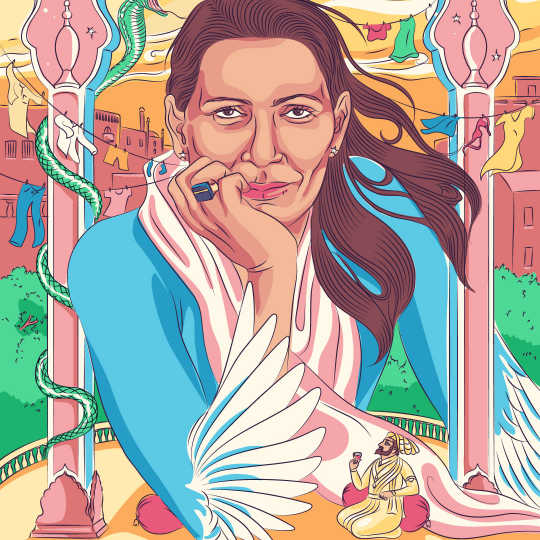

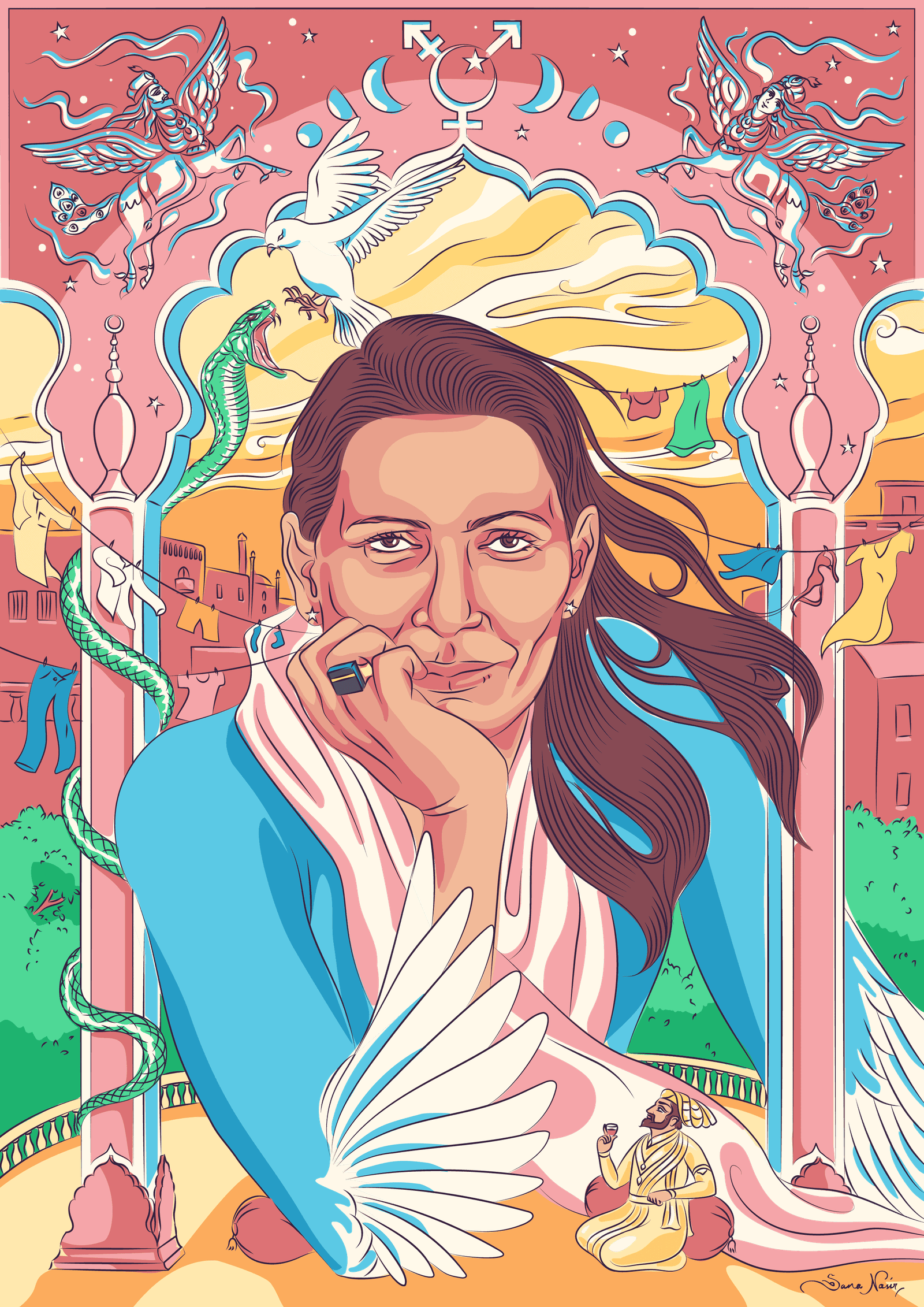

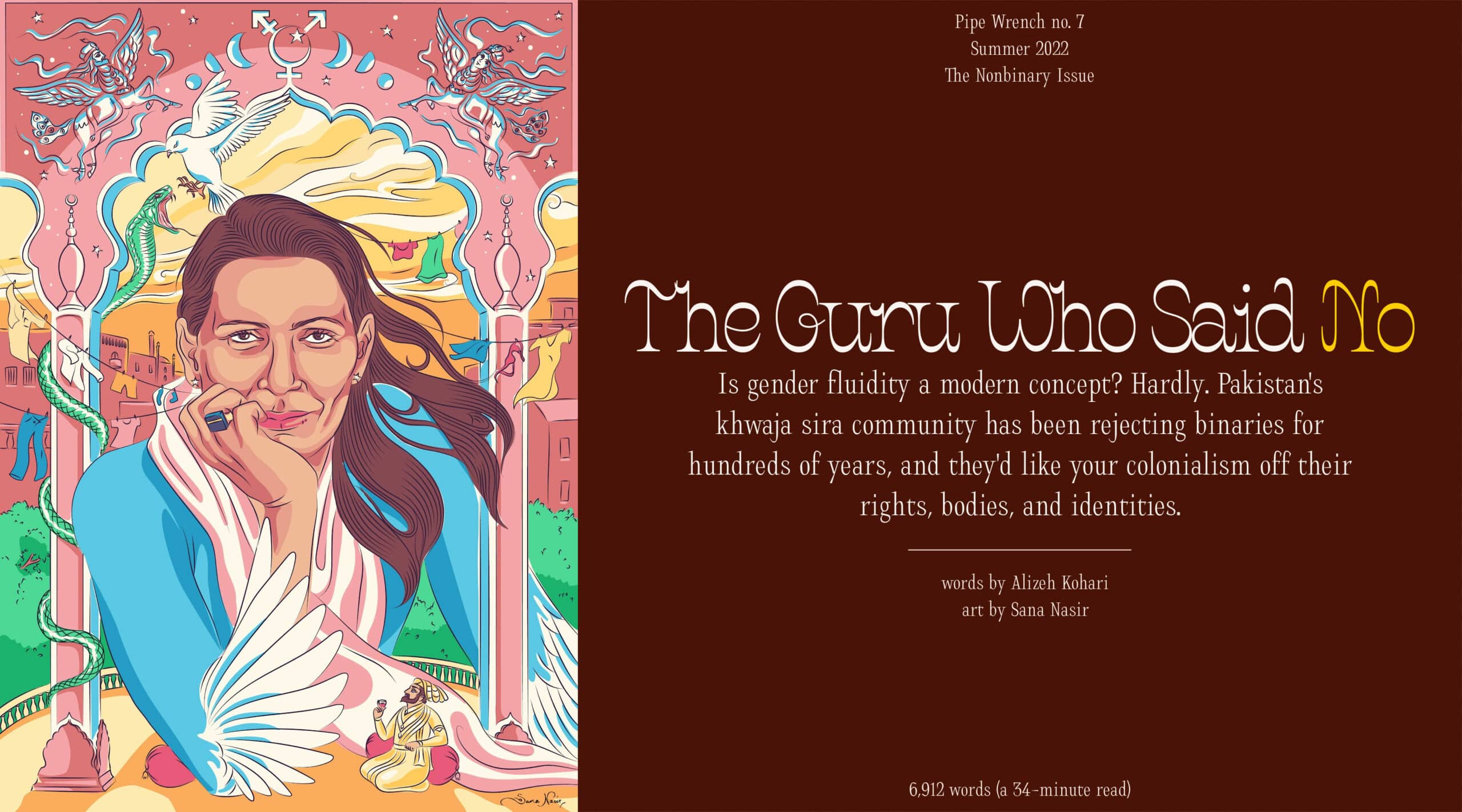

Sana Nasir is an international award-winning Illustrator and graphic designer. She has worked in music, art education, publishing, and activism, and spearheads a series of talks “Freelance Ain’t Free.” Nasir resides in Karachi under her artist name, Koi Nahi, and is currently art director for Cape Monze Records and adjunct faculty for illustration at the Indus Valley School of Art & Architecture.

***

Editing and layout: Michelle Weber

Fact checking: Matt Giles & Zuha Siddiqui

next

Fragments of Grief

Sophia-Layla Afsar